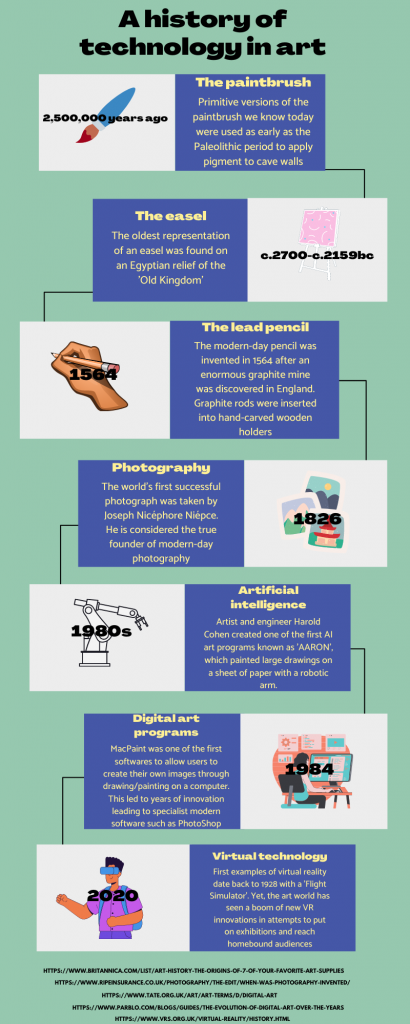

(Solid State (2015), courtesy of Jake Elwes)

Around 60% of people say they are viewing more arts and culture content on digital platforms than ever before following the pandemic, according to a recent study. How is this increased use of technology changing how artists and audiences create and experience art for the better?

When media artist Jake Elwes exhibited his artwork at the end-of-year art school exhibition several years ago, he received mixed reviews. “I just don’t get it,” said one critic. “Why are you doing this?”, “What are you trying to say?” said others.

Viewers watched a display of luminescent colours morphing into an infinite array of forms and shapes, created using an AI algorithm. It was something many had never seen before.

Yet, despite this tentative feedback, Elwes knew this new artform was the future.

With the loss of the physical art world over the course of the pandemic, professional artists were forced to find new ways to connect with home-bound audiences. Virtual gallery exhibitions and interactive art activities were accessible everywhere, providing free access to respected artworks across the globe.

However, artists such as Jake Elwes, a London-based media creator, saw an opportunity to push the boundaries further and bring exciting modern art into people’s homes. Using emerging technologies such as AI and machine learning tools, Elwes created his most recent work ‘The Zizi Project’ (2020).

The project is an interactive drag cabaret that uses ‘deepfake’ technology. Audiences are given the opportunity to decide how drag queens perform and dance. For Elwes, this was not only an opportunity to break down fears about artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, but also to improve audience access to new art forms.

“I wanted to make something really fun, celebratory and playful, that can hopefully be a lot more accessible for a wider audience,” said Elwes. “The art world’s not particularly accessible and the AI world definitely isn’t.”

The gaming world has also been used to bridge the gap between the art world and audiences who may not normally visit traditional art spaces. To make up for their cancelled exhibition in April 2020, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collaboration with Nintendo’s Animal Crossing saw the designs of William Morris become available to players, giving them the opportunity to decorate their virtual homes with his designs. The artist Simon Denny also used the popular game Minecraft to create an online version of his exhibition at the German art gallery Kunstammlung called ‘Mine’.

Increased digital access to art appears to be a success, as 2021 study by the Audience Agency found that 60% of respondents said that they were viewing more arts and culture content online (digitally) than before the pandemic. Going forwards, 40% said they would look to engage with arts and culture online and in-person.

For Elwes, these kinds of technologies are not only opening doors for audiences to experience art in different ways, but also providing new avenues for artists to explore and create.

“There are more and more tools coming out now which are empowering artists and creatives to use these sorts of things without having a background in code, which is really exciting for me,” Elwes said.

For some UK artists however, digital platforms and technology were incorporated in their practices out of necessity and many of which were initially hesitant to do so. In response to the closures of galleries and art studios in March 2020, Digital Advisor and Producer Suzy Glass, developed the Digital Pivot Programme, aiming to advise artists and organisations in the best ways to digitally produce and display their works.

“The Digital Pivot Programme came specifically out of that moment of need,” said Glass. “Where suddenly there were a huge number of artists and organisations that were confronted with this absurd operating environment, where they no longer could rely on their skillsets and the knowledge they had in order to connect with their audiences.”

Having noticed a large number of arts organisations digitally exhibit artworks in unadventurous and unsuitable ways, Glass began to encourage artists and institutions to develop more participatory experiences for viewers and create platforms which are better suited to displaying particular artforms.

“What had happened was a lot of organisations had thrown work online without revisioning it, and actually without talking with the artists,” said Glass. “If you are putting art online, then the art should be conceived and made for that space. This includes thinking about that most people are engaging with the online space through a landscape computer or through a portrait phone.

You need to think about the particular joys that the online world can bring you, so the depth, the ability to move through pages, and hyperlinking. These are all the characteristics of the space.”

With these things considered, Glass expects to see more and more artists developing artworks and artforms to be exhibited specifically in these alternative spaces.

One of the most striking realisations Glass had during the early stages of the program, was that the adoption of digital tools and new technological skills were giving artists more autonomy and freedom than they’d ever had before. These tools and skills are already beginning to be able to challenge the inner workings of the art world, she says, through giving artists a new-found freedom to take control of the way they want to create, exhibit and sell their own art, without having to be taken on by an art gallery.

“I am interested in the next generation of artists, who don’t need to work with the technologists, who can be technologists and artists,” said Glass. “They are challenging what the interface is between them, the art and the consumer.

The thing I’m most interested in, is how people go to the edge of digital tools and technologies and really tear it up and push at it. This is now endemic, we are now hybrid, digital, real people.”

However, even the simplest forms of technology have shown to have some big impacts on the art world. Through the simple Instagram hashtag ‘#artistsupportpledge’, artist Matthew Burrows MBE was able to build an alternative global art market and community known as The Artist Support Pledge, within the space of a few days. By using the hashtag on the social media site, a platform with billions of users, artists were able to promote and sell artworks on an international scale.

Whilst the use of technology was simple, Burrows used the Artist Support Pledge to propose an alternative and fairer economic model for the art market. All artists were asked to sell artworks for no more than £200 each, once they reached £1000 in sales, they pledged to buy another creator’s work. With this, Burrows hoped to instil a ‘generous culture’ or a ‘reciprocal cyclical economy’ within the current art market.

“I came up with the pledge because I thought it’s got to be something that’s generous,” said Burrows. “Rather than a culture of hyper-competitiveness and every man for themselves, which is tended to be what’s happened over the last 15 to 20 years in the art world. I believe that we are all much better off if we actually support one another.”

The pledge allowed artists to take full profits from their art sales and provides a free space for them to exhibit their work. This cuts out gallery commissions on artists’ work, which can range from 33-100%, according to Artquest.

“It’s very difficult to get into the gallery system, and even when you’re in the gallery system it’s very hard to sell the work and to stay in it,” says Burrows. “It is the system, and I don’t expect anyone to change that overnight, but I’ve always thought it odd that there isn’t another one,” said Burrows. “I sort of felt that as an inventive, creative sector, why can’t we come up with our own economic models?”

As more and more artists begin to find alternative ways to reach audiences and turn away from formal gallery routes, questions have been raised about the future of traditional art institutions.

“I think the building-based infrastructure will disintegrate,” says Glass. “I think there will be funding cuts to the arts councils direct from government and obviously local authorities are going to be obliterated over the next 5 years just because of the costs of dealing with the last 2 years. Artists are going to have to circumvent it.”

Despite the Artist Support Pledge starting online and providing better freedom to artists, Burrows hopes to prevent this deterioration of the physical art world.

“Artist Support Pledge is not a replacement for seeing art in the real world, or a replacement for the art gallery sector as it is, said Burrows. “It’s just an add-on, its like a bolt-on, you know, it’s a sort of an extra bit of the ecosystem that just gives a little bit more freedom and a little bit more accessibility to artists, makers and buyers to survive and thrive.”

Burrows plans on bringing the Artist Support Pledge to the real world in a physical art exhibition. Mimicking the format of the online version, visitors will be able to access the artist’s online page and buy the work directly from there through a barcode displayed next to their works.

“It gives the museum an opportunity to support artists by sharing their work, but also it allows them in a really light touch way to sell their work without having to do all the leg work,” Burrows said.

Digital platforms and selling art online have also begun to benefit the general public too, says Alice Black, former director of the London Design Museum and founder of artist support organisation, Art Ultra. With artwork more available than ever to buy directly from artists, she hopes that the elitist art buyer stereotype will be challenged and that everyone begins to buy original art of their own.

“I want to encourage this movement of buying original stuff by emerging artists. It gives you a thrill that you don’t get if you buy a reproduction of artwork,” she said. “You can find something as a gift for yourself that is incredibly original and that has been created by living artists. You are making a big difference by selecting that option.”