Indians have become the second-largest foreign student group in Britain, but many of them are on student loans. What are the financial and psychological challenges faced by them?

It’s a warm Saturday night in Cardiff, and 25-year-old Padmakshi Pillai crashes face down onto the bed. She has returned after her 10-hour shift at an Indian restaurant. The sound of people heading out to pubs and partying on the streets rings in her ear, but that is the least of her worries. There are three missed calls from her mother, and she must gather the energy to freshen up before answering.

Padmakshi does not want her mother in a South Indian city to know she has worked over 85 hours in the past eight days, violating her student visa rules, and yet made only £680, barely enough to scrape through the month.

“She’s always afraid of what if someone catches me. She can’t know that I come home after midnight and go to sleep at around 3 AM,” says the 25-year-old optometry student.

The restaurant paid her £8 per hour, the minimum wage in the UK is £12.21, and made her work four times the 20-hour per week limit imposed on foreign students. If caught, she may be deported back to India, but it is a risk she is willing to take.

Padmakshi, who asked for her name to be changed for this story, got a student loan of nearly £38,000 to study at a British University. She says she is working to pay for her living expenses here because she is deeply in debt and her family has barely any means to pay back if she defaults.

“The loan company is charging me 12% interest. I have decided to use that money only for my tuition fee payment. I cannot afford to use all that money for my expenses. That’s why I must work and pay for my living here,” she says.

Chetan Singh, an Indian student working in a Newport warehouse, says he rarely spends money on anything but groceries and rent.

In December last year, he could see the shiny rides and the giant Ferris Wheel at the Cardiff Winter Wonderland from his student accommodation, but never had enough money to enjoy one of them.

“It was a five-minute walk from my accommodation. My friends were there, and they invited me, but I knew I couldn’t afford to go,” he says. “Look at the cost of everything here, and on top of that, we have the exchange rate problem. When I came to the UK, one pound was around 105 Indian Rupees. Now, it’s around 117. I am using an app to get free groceries. I can’t ask my parents for money to go to Winter Wonderland.”

Padmakshi and Chetan belong to middle-class Indian families. Padmakshi was working as an optometrist while Chetan was a public relations professional. Both were making around £250 per month. But they came to the UK for a master’s degree, hoping it would provide a better life.

They live with Indian flatmates who are on student loans. Just like them, many of their friends are also working in shops, restaurants and warehouses, at times, in violation of local laws and immigration rules, to fund their educational dreams.

Apart from the constant fear of being reported to the authorities, the working conditions at many of these places can be gruelling. Workers are made to stand on their feet for hours, paid half the minimum wage and their salaries are withheld if they quit the job without notice.

“Who are you going to complain to? We know we are violating the law; we can’t go to anyone and say we are being paid £8 an hour,” says Chetan.

The loan company is charging me 12% interest… I cannot afford to use all that money for my expenses. That’s why I must work and pay for my living here, Padmakshi.

History of Indian students in Britain

Colonial ties have historically rendered Britain an appealing destination for students from India. The first Indian to take a UK degree was Dhunjeebhoy Nowrojee in 1843. He was a Parsi convert to Christianity who studied theology in Edinburgh.

The British Raj required qualifications from UK universities for entry into professions such as law and civil services, leading many Indians to obtain degrees in Britain. Mahatma Gandhi, for instance, spent three years in London training to be a barrister in the 1880s, and India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, studied at Cambridge and then Inner Temple in the early twentieth century.

Srinivas Ramanujan, the famous mathematician and the inspiration behind the movie, The Man Who Knew Infinity, studied at Cambridge.

Siobhan Lambert-Hurely, a professor of Global History at the University of Sheffield, records that by the interwar years, as many as 1,800 Indian students were in the UK at any point.

Numbers skyrocket post 2021

At the turn of the millennium, the Indian student population in the UK was relatively modest. An estimate by UNESCO suggests that around 5,000 Indians were enrolled in British universities at the time. Growth was gradual over the next two decades, but the numbers skyrocketed after 2021.

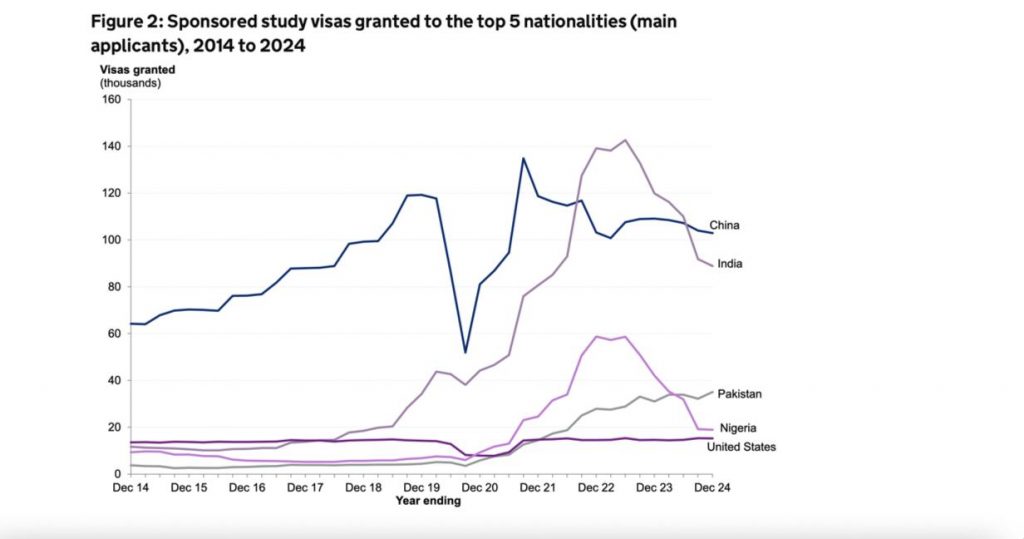

According to the UK Home Office, 136,921 Indian students came to the UK in 2023, a nearly tenfold increase compared to 2013, when only 13,608 study visas were granted to Indian nationals.

The latest Home Office data shows that in the year ending March 2025, there were 102,726 sponsored study visa grants to Chinese applicants (25% of the total), followed by 98,811 Indians (23%). Pakistani and Nigerian nationals were distant third and fourth.

For a brief period between 2021 and 2024, India overtook China as the largest source of international students in the UK. However, Chinese students have since regained the lead.

Expanding middle class and, lack of good universities are pushing Indian students abroad

Experts say that the increased competition for admission into top Indian institutions, the rise of the middle class, the craze for foreign degrees and the desire to settle in a foreign country are driving the country’s youth to the UK.

“Almost all of these students are coming from comfortable, middle-class backgrounds, and they come from a country with many exciting work opportunities,” a 2012 study by Leonard Williams revealed.

After tracking the Indian migration in the UK, Williams found that students at British universities were not poor migrant labourers but aspirational youngsters.

“They come from states which are doing well. But many feel that they are not valued and paid well enough for their skills in their home country… These middle-class Indian families are willing to spend money on education, but there is a serious lack of good universities in India,” he found.

Student motivations have changed little in the last 13 years since Williams’ research, but the rising cost of education at private Indian institutions has added another dimension.

Maheshwer Peri, founder of education and career guidance platform Careers 360, says there are several universities in India where completing a four-year degree may cost a family £50,000, but the quality of education provided is found lacking.

“So, they think they might as well spend £20,000 to £30,000 more and get a good degree,” he says.

Education funding through high-interest loans plunging students into debt

When Padmakshi secured admission to her dream university, the next step was to manage funds. She gathered her identity proofs, account statements, and salary slips and applied for loans at half a dozen banks.

“Everyone refused,” she says. “My parents do not live together, and we have no shares or investments to give as surety. Even the property documents are not good enough for a loan.”

Ultimately, a non-banking financial company (NBFC) sanctioned her loan, but the interest rate shocked her.

The interest was further increased by half a percentage point within a few months of Padmakshi landing in the UK.

“They know if we are coming to them, we have exhausted all our options and they can charge whatever interest they want. My loan was sanctioned at 11.5 per cent, and within four to five months, I got an email saying the interest rate has been raised by 0.5 percent,” she says.

NBFCs are financial institutions that provide many banking-like services but do not have a banking license. They often cater to borrowers with lower credit scores, self-employed individuals, or those underserved by banks. This higher-risk borrower profile means they charge much higher interest rates compared to traditional banks.

While there is no publicly available data on the exact number of Indian students in the UK financing their education through loans, trends suggest a strong correlation. The post-pandemic surge in Indians pursuing higher education abroad has been accompanied by a parallel rise in applications for education loans, particularly from NBFCs, which have become a major source of funding for families lacking collateral or strong credit histories

In India, there is nothing called an education loan of over £3,500. Every other loan here is an NBFC loan, Maheshwer Peri.

A 2024 report by credit rating agency CRISIL shows that the education loan assets of NBFCs have boomed by over 80 per cent and 70 per cent in the years 2023 and 2024, respectively. Foreign education loans are the fastest-growing segment for these lenders today.

Peri says Padmakshi’s case is not unique and that people are turning to NBFCs because traditional banks are reluctant to give education loans.

They ask for surety, collateral and income certificates, which many Indian families cannot furnish, he says.

“It is a sorry state through which India is going,” he argues. “Banks ask for multiple things. They will ask you for the income statement and whether the income can support the monthly instalments. If a family had that income, why would they apply for a loan? Most of the Indian families cannot provide these things.”

Peri adds that NBFCs are not actually providing education loans, but rather extending general credit that can be used for any purpose.

“In India, there is nothing called an education loan of over £3,500. Every other loan here is an NBFC loan. The purpose is education, but you can do anything with it. You can do trading. Tomorrow, you can name it a genius loan,” he says.

He believes that educational services and study abroad companies have misled students and says many students who have taken these massive loans, which may lead to many defaults.

“India will see a lot of pain and broken promises, debt and non-performing assets (NPAs) in the years to come. However, as all good marketing companies do, they [education services companies] will still talk of the anecdotal stories and will get many more students sucked into this,” Peri wrote on social media a few months back.

An Indian dream or necessity to work in the UK?

For students like Padmakshi, the Graduate visa, restarted by the UK government in 2021, allowing international graduates to stay in the country to work or look for work after studies, is the only way to recover the investment they made in their education in the UK.

“When you take such a big risk and invest all your life’s savings, you need to recover the money well,” she says.

A 2024 study by the Migration Advisory Committee revealed that in 2022, the first full year of the Graduate route, 66,000 Graduate visas were granted for main applicants and dependents. This more than doubled to 144,000 in 2023.

Indians are the biggest beneficiaries of the scheme. The report, commissioned by the British government, also found that four in ten graduates applying for graduate visas in 2023 were Indians.

It was discovered that only 10 per cent of graduates from top universities (ranked between 1 to 200 globally) applied for the graduate visa. Thirty per cent of the applications came from students who had completed their studies at universities ranked 800+. Further, 66 per cent of the graduate visas went to graduates from non-Russell Group universities.

I know I am in debt, but I am studying what I am passionate about, Padmakshi.

The mounting loan also means Padmakshi cannot go back to India before paying a significant chunk of the debt.

Salaries in her home country are a fraction of the monthly loan premium she would have to pay.

“An optometrist in India makes around £250 a month. The instalment on my loan would be more than £600. There is no way I can go back before paying the entire education loan”, she says. “I told my family that I am borrowing the money at my risk, and I will pay it. Now, I can’t go back to them and ask for help. Anyways, I don’t think they can help me.”

These worries keep her awake every night and will continue to do so till she finds a good job here but she believes the risk of uprooting her life in Indian and coming to the UK was worth it.

“I know I am in debt, but I am studying what I am passionate about,” she says.

Meanwhile, as her mother calls her the fourth time, Padmakshi answers with a wave and a smile on her face.

“Everything’s fine here, ma. How are you?”