While the Pegasus scandal reminded the world of the dark power of data, digital surveillance continue to target dissidents – everyday, everywhere. UK activists are educating themselves to resist the fragility of living in a digital society.

Amber Macintyre does not seem too scared of digital surveillance. That is not because she is unaware of the privacy implications that come by using smartphones and social media. Quite the opposite, she learned to quell them. She simply knows how to protect her personal data in the cyberspace.

This knowledge was something that she felt the need to develop and then share with the most vulnerable, like activists and campaigners. With her PhD, Amber began to explore ways to support the work of organisers. Especially, she was concerned at how they could better protect attendees’ data when setting up events. She then joined the Berlin-based Tactical Tech. An international NGO, it aims to engage with citizens and civil organisations to mitigate the impacts of technology on societies at large.

“The fear around is really important to how Tactical Tech works because people do become a bit overwhelmed and then it’s hard to feel you can do something to change it. It’s important that we take a bit of agency back. Because we feel there’s such big players and such technologies are so embedded in what we’re doing. We need to feel we can actually control it,” she said.

New activists and campaigners discover very soon the threat of digital surveillance. In an online world, it is easy getting noticed, profiled, targeted. For instance, Kill the Bill organisers said to have been experiencing police pressure since the first demonstrations. After putting some names and Instagram tags on their posts, they realised that the police would target specific individuals. They would then go around at all the protests happening that day across the country and ask for those persons by name.

“It was quite scaring,” said Bily, who was involved with the Kill the Bill movement since the beginning. “From the very start they were looking at what we were saying. Since then, obviously there’s an element of paranoia.”

This is not an isolate case. UK activists have to contend with the dark side of digital technology on a daily basis. If smartphones and social media made it easier for activists to mobilise citizens and coordinate actions, the surveillance tendency that characterised these digital tools also brought a heavy downside.

Every time we use these technologies we leave behind some digital traces. These can be sensitive information, as a name or an address. Or records of our online activities, what we like and do not. Governments use these data with the promise of keeping us safe. Commercial corporations collect them to make our life easier, customised, smarter. Hackers may steal them for threatening our identity, our security.

For digital rebels, data leaks are something that could compromise all their work. In some cases also their liberty, or even their life. As Amber from Tactical tech said: “Information can just go into the hands of the government in places where the government and activists are opposed to each other.”

Movements grow by expanding their networks, and when it comes to surveillance, networks are as weak as their weakest point.

Zeynep Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas

The beginning of what Columbia professor Andrew Ferguson called big data policing means that social movements need to find a way to operate amongst a regular police pressure. As Zeynep Tufekci pointed out in her book Twitter and Tear Gas: “Their ability to shift their protest tactics is often a key determinant of whether they can survive in the long term.” This brought to the growth of a new form of digital resistance. Instead of challenging this datafied society from the streets, digital rights campaigners seek to give back control on the hands of dissidents.

Amber Macintyre is now the Project Lead of Data and Activism, one of Tactical Tech’s research projects. It aims to examine how data collection and profiling affect human rights defenders, activists and networks. They then share their findings in accessible guides and reports for spreading their knowledge.

She explained that even if digital surveillance is something bigger than us, that does not mean we should stop trying to take control and feel so fearful of it to just back away. “Because the only way we can take agency over something is to try to,” she said. “Tactical Tech works just on this: education can be liberating in itself.”

Few months ago it has been the Pegasus App to remind us of the danger if these data end up in the wrong hands. For instance, investigations found that NSO’s technology was used to target the phones of people close to the journalist Jamal Khashoggi during the months after his murder.

But the real turning point occurred in 2013, when the US whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed the surveillance practices of organisations like the NSA (National Security Agency) and the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). Then, there was the scandal of Cambridge Analytica in 2018 to clench our dreadful fears. Collecting personalised data also allows to manipulate citizens’ decision-making during elections.

As Cardiff Professor Lina Dencik pointed out, these scandals confirmed that governments engage in mass digital surveillance on their own citizens. They also showed that corporations share these data with governments, to mutual advantages. By using social media and smartphones, citizens are the ones who decide to participate in this data exchange. It is not really a choice, but more a feeling of necessity.

“Citizens are traced and tracked in all kinds of aspects of everyday life, with the purpose of continuous monitoring and profiling,” she wrote in the book Digital Citizenship in a Datafied Society.

Nobody is exempt from the watch of what professor José Van Dijck renamed the platform society. If this scenario might be worrying for many citizens, for dissidents it represents a real threat. Digital surveillance targets activists everywhere around the globe, even in the most democratic countries. As sociologist Tufekci wrote in her book: “Movements grow by expanding their networks, and when it comes to surveillance, networks are as weak as their weakest point.”

In the UK, digital rights and privacy campaigners have been sparking concerns about how authorities monitor activists and protesters. For instance, many criticised the 2016 Investigatory Powers Act. It brought new powers to gather and retain data on citizens as well as to force tech companies to exchange the data that they have about people with intelligence agencies. At the time, Liberty’s director Shami Chakrabarti commented on BBC News that the bill gave authorities new abilities to hack into citizen systems, servers and devices “in a way that leaves us all more vulnerable.”

Amber from Tactical Tech explained that there are different set of threats for activists within the cyberspace. Digital surveillance brings a very physical risk. Data can reveal their identities, the places they frequent and what they do. This can also compromise their own security. Not just governments profile and monitor dissidents, but also other activists groups that disagree with their cause.

KTB rebels discovered quickly the physical implications of operating in a digital world. There, everybody can watch and monitor your activity. “We do these things called file facts, where we described the route and some horrible facts for giving people information about the places that we’re going to walk past,” said one of the organisers. One time, huge swarms of police were waiting for them at one of the stops. “They’re watching what we say we’re going to do and then they use that to inform how they’re going to police us.”

British authorities use intelligence gathering methodologies like SOCMINT (Social Media Intelligence) and OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) for policing protesters. For example, social media monitoring allows the collection and analysis of a large range of data. Officer used them to generate profiles and predictions about users. This means that police can learn the identities of the organisers, their affiliations as well as the location and timing of a planned action. They can also identify who take part to the demonstrations.

There is also a general power imbalance of influences around politics. Powered by algorithms, personalised information contribute to create an always more polarised society. Plus, Amber from Tactical Tech said that it has to be taken into consideration the degree of effectiveness and bias of the data itself.

For digital rebels, data leaks are something that could compromise all their work. In some cases also their liberty, or even their life.

“In two different contexts the same tool can be the right choice of the wrong choice. The risks are really personalised,” she said. Even though security and surveillance are important concepts to explore, Amber thinks that they are not the only lens for engaging with digital technologies.

She said: “I think that talking about the values that are embedded in these tools should also be taught. We should also be questioning, when I use Facebook what values am I agreeing to and did I want to? And when I use Google, what values does Google have and are they the same as mine? And it doesn’t mean political values necessarily, although that’s part of it. It also means just how are they making me see the world?”

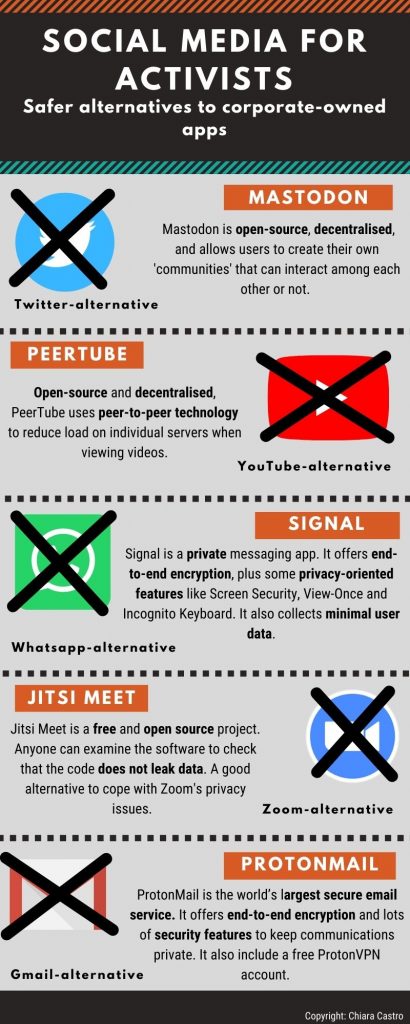

The necessity for more ethical technologies brought to the development of alternative applications. These work according to a decentralised, free and open source software (FOSS). Activists’ guides are proliferating amongst social movements, listing safer apps and ways to improve online security for eluding digital surveillance.

Activists’ best weapon is indeed limiting the risks, as much as they could. “People have educated us on staying a bit safer online,” said the KTB activist. “Once you know that they’re watching, you then have to worry more all the time.”

They said that their self-defence has been a process that they have been figuring out as they go along.Organisers use Signal instead of WhatsApp for exchanging sensitive information. The video conference app Jitsi, which appear to be less vulnerable to hacks, is preferred to the more popular Zoom. VPN (Virtual Private Network), Tor browsers, secure email services, like ProtonMail: these are tools any contemporary activists cannot afford to overlook.

“I think you’re never completely safe online, but things like VPNs are really good,” said Bily (not real name). “It’s quite difficult to just invite people on the Internet because we don’t know if they’re spies or what. Especially at the beginning because of COVID being it was illegal to organise anything.”

Although, the information gathering does not happen online only. The police may use mobile phone extraction (MPE) tools to obtain data from protesters’ smartphones. Officer also used IMSI catchers to identify demonstrators by intercepting calls and texts. Geo-location technology to monitor if the targets are attending a certain event.

This is why privacy campaigners suggest to enhance the security setting on your smartphone before going to a protest. It could be deactivating the geo localisation feature, or making sure your phone do not contain sensitive information. Also avoiding to post on social media and keeping the airplane mode during demonstrations are effective ways to elude police tracking.

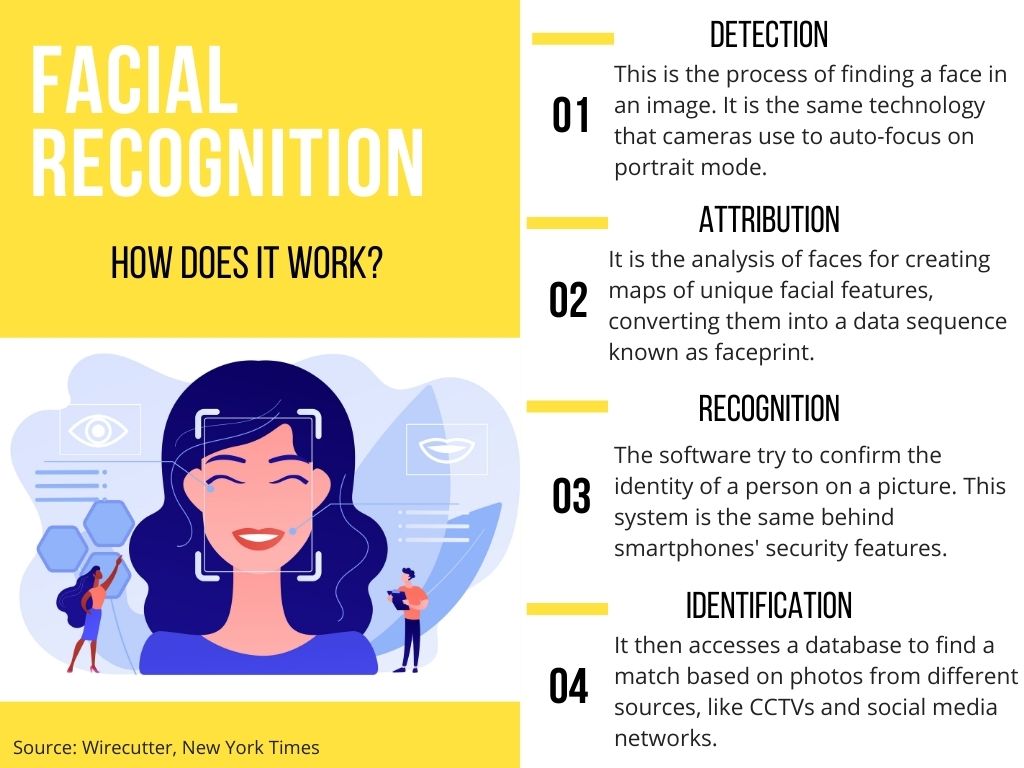

UK authorities used facial recognition (FR) and gait recognition technology (GRT) to monitor protesters. Not to be mistaken with CCTV cameras, these tools are much more invasive. They indeed extract biometric data, which are unique features of our bodies and behaviours. It can be a face print, unique map of a person’s face, or simply the way someone walks. Once collected, data go to feed databases or watchlists of possible targets.

On this point, Bily said: “Some people explain to us that when there are photos of protests online, they use facial recognition to catalogue all the people that were at the protests.” For this, activists suggest to blur faces before publishing them on social media. Plus, photos carried with them metadata, like location and time, that could reveal more than people think. Campaigners recommend to be sure to eliminate this information before posting any image.

FR’s supporters believe that it is a necessary tool for keeping citizens safe from terrorism attacks and other crimes. It indeed makes it easier to monitor suspects in large crowds as well as to increase security at airports and borders. Outside law enforcement’s practices, the use of facial recognition is a more secure way of protecting your phone, laptop and online accounts.

Despite this, critics argue that this indiscriminate use of biometrics could lead to unlawful mass surveillance. Indeed, the 2019 report of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee recommended to stop the use of facial recognition technology until the introduction of a legislative framework that could better oversight its use.

Many have also criticised their degree of effectiveness. A test ran in 2018 in London showed that among 104 matches, only two were true positives. Researches also suggested that the bias of algorithm can reproduce social inequalities. It has indeed proven that a darker skin or asian complexion can enlarge the margin of error. However, FR developers suggest that the softwares are not meant to be discriminatory. They also ensure that human mistakes are more common with non-digital investigative practices.

In 2020, the privacy advocacy group European Digital Rights (EDRi) launched the campaign Reclaim Your Face. A coalition of 60 different European organisations, amongst which Big Brother Watch UK, Algorithm Watch and Article 19, are calling for the ban on the use of facial recognition technologies for mass surveillance.

Through their social media pages activists groups tirelessly promote ways to protect themselves at protests, like using masks or wearing black clothes for getting unnoticed. Others go even further. Dazzle Club‘s campaigners aim to beat Met surveillance wearing anti-facial recognition makeup able to elude the algorithm.

The need for social movements to engage with a wider public make it difficult for activists to be completely out of risks. “Even when we are security conscious and doing everything we could, we’re not free from surveillance. That’s in part because the government can do so,” said Amber from Tactical Tech, “there needs to be much more accountability and transparency.”

Authorities and rival groups constantly exploit the power of data collection technologies to fight back activists actions. Social movements are well aware. This is not likely to change in the near future. Learning to deal with the implications of living in a digital society is therefore a big part of the game for those who decide to put themselves on the front line.

“I think a lot of the time we just have to accept that they’re following us,” said Bily. “That fear can eat you up and make you think that you shouldn’t be doing what you’re doing. But actually, we should be doing what we’re doing. It’s a decision for everyone to make for themselves of how much they want to risk.”