Each year, the UK sees over 100,000 Indian students but their experience in the country varies according to where they find themselves. Indians currently studying in the UK tell us about how their time in the UK helped them think about themselves and the place they had come to.

Though everyone around Prakhar Gupta, 26, told him that London would be the best place for an Indian student to live in the UK because of its diversity and vibrancy, he wanted to see it for himself.

He always knew that the UK’s capital would be the perfect place to enjoy his time abroad and stay close to his culture, with London’s famous South Asian-influenced neighbourhoods such as Southall and Wembley.

“I did the unthinkable of eating beef on a fine Friday evening and without knowing for the first 10 minutes, I thoroughly enjoyed it,” he said. “Coming from a traditional Hindu household, it felt like I had committed blasphemy, but this was just the beginning.”[i]

Like many religions, Hinduism forbids the consumption of certain types of food for different sects. For Hindus who are allowed to eat meat, it is forbidden to consume beef (cow meat).

Back home, Prakhar strictly followed religious codes passed on to him by his parents during his formative years. When he was leaving for the UK, his exceptionally religious family only asked him to stay true to his faith, and ‘gain strength from God when in trouble’. Unfortunately, he could not stay true to his word for long.

“I imagined it being easy to stick to my roots, with London being the perfect place to find Indian restaurants, cultural events, temples, and fellow Indians to socialise, but it turned out I was not meant for these,” said Prakhar.

Unlike most international students, some of the first friends he made were locals instead of Indians which helped him get to know the city and its ways in no time. He realised that his preferences and style were changing with his current environment which he liked way better than what it was like back home.

“I was brought up as a very religious and culturally inclined person which I perceived as normal when I was home. Festivals such as Diwali and Holi have been very significant for my family for generations,” said Prakhar. “Turns out, I only liked them for being cultural and social, the religious part was more for my family.”

The 26-year-old was on a date when he realised what he had eaten when the manager informed him that they had provided him with a beef dish instead of a chicken. Though he was almost ready to fight him, he realised it was probably for the best.

“Staying away from home, I could not connect with my culture very well, especially ones that seemed unnecessary to me,” he said. “Free from my family’s influence, I began to see there was not much logic in not eating beef or not getting a haircut on Tuesdays and Thursdays. I was glad to be able to make my own choices now.”

Living in London, Prakhar assimilated into the local culture fairly quickly in ways like picking up British slang, visiting pubs almost every day, dressing like how a Pinterest British guy would and enjoying football and rugby as he had never before.

“I mostly have British mates they got me into Premiere League which I enjoy more than I have ever enjoyed cricket in India. Going into a pub and watching a match with a pint in hand became my weekly activity and I got immersed in my new life detaching from home,” he said.

Prakhar had met many Indians around him but had never aligned with their ideas or opinions. He found some pretentious and backward people, eventually avoiding them altogether. “They seemed pretty ethnocentric as I saw a certain group of Indians only talking in their languages such as South Indians only speaking in Telugu or Malayam, or Maharashtrians speaking Marathi, not attempting to interact with Indians from other states in either English or Hindi.”

I was brought up as a very religious and culturally inclined person which I perceived as normal when I was home

Prakhar Gupta

Though he made peace with not getting along with Indians, and only enjoying the company he had, he did realise it was partly unfortunate that he could not connect with people from his country well. “I saw how they would get together for cultural events in Wembley or East Ham and take part in Indian festivals while away from home,” Prakhar said. “It was sad that I did not have anyone to join these cultural celebrations with, even if it was just twice or thrice a year.”

Immersing in his new surroundings and adapting to the British culture made him develop an agnostic perspective, drifting away from Hinduism. Prakhar knew his family would accept it easily and thus avoided talking to them as much as possible.

“In the first year, I was having the time of my life travelling through Europe and trying new things in Britain while doing my university life,” he said. The engineering student only cared about his present life, drifting away from familial, cultural, and ethnic ties.

Delhi University’s Dr. Shreyasi Chatterjee, a professor of Sociology refers to the deep impact of the assimilation of international students in Western countries when they are pursuing their degrees, and how it affects them in the long term.

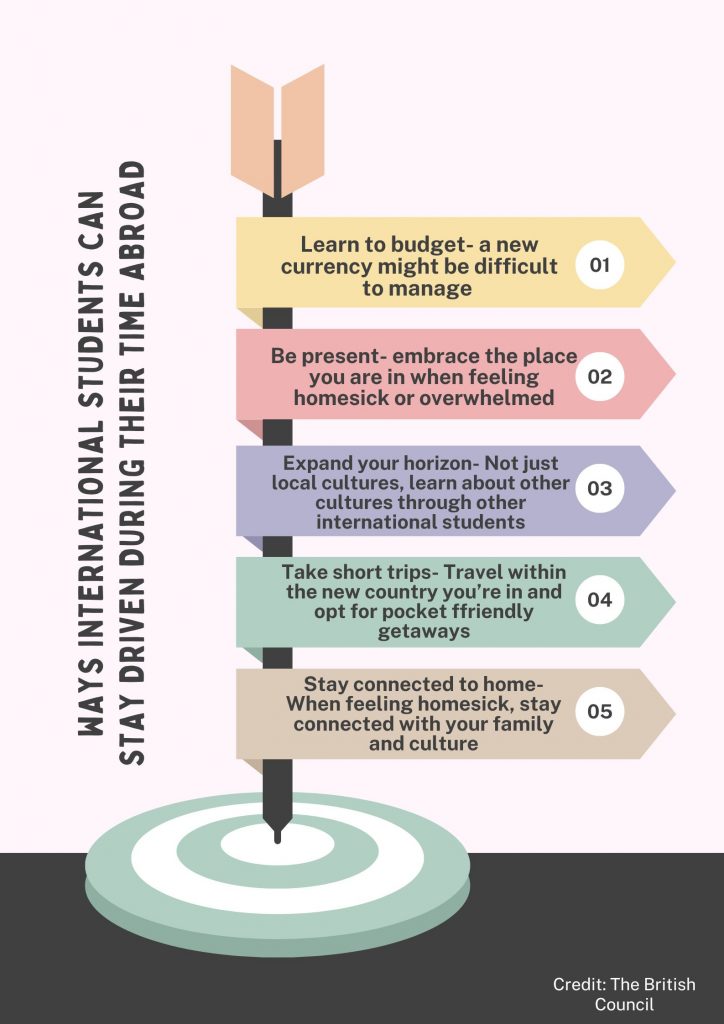

“Exposure to a new country’s culture can have different effects on different people such as some get more attached to the culture, they came from to feel safe and accepted, interacting more with people from their own countries and participating in cultural events to deal with homesickness,” she said. “Keeping in touch with families and visiting them often helps them feel better at difficult times and cope with challenges.”

Dr. Chatterjee goes on to talk about the impact of a student getting completely pulled into the culture they go into. “For such students, the transition is much easier than ones sticking to their roots. However, they often land in a struggle between two identities where they do not feel at home in either country.”

Prakhar regretted being disappointed in his family while being away from them and drifting away from his old self while discovering a new place. “The time when international students are away from home, we only focus on the now instead of looking back at our homes. The homesickness sets in pretty late, and if someone gets detached from their culture like me, it would be very hard for them to find comfort in either of the countries,” said Prakhar.

When Shivam Shah stopped having a normal university experience from the moment he got on a bus back to his accommodation from his university, an old Irishman asked him to get off the bus right before spitting on his face and yelling racial slurs.

It was only his second month in the UK when he fell victim to this traumatic incident where no one other than the bus driver came to his help when the attack got almost physical.

“I was in shock for a minute when the old white man spat on my face calling me names like paki and brown rat. My presence clearly triggered him from the moment he saw me getting on the bus,” said Shivam.

The 25-year-old came to Belfast to begin his postgraduate studies, he did not expect Northern Ireland’s capital to be so racist for him to fall victim to two abusive incidents within six months.

The second incident occurred on a February night when he got out of a pub early without his friend who had accompanied him there. As he lit a cigarette while waiting for a bus, a voice came from behind: “Indian guy, give me one of your cigarettes.” In a matter of minutes, the local called five more people. When they bullied Shivam into giving them all cigarettes, he tried to politely refuse.

“At my refusal, they said, ‘Stop stealing our jobs if you can’t give us cigarettes’ and ran away when they heard a siren from nearby. They were drunk and were determined to corner me into a fight. I am glad I could handle the situation before it got worse,” he said.

Between the occurrences of the two incidents, Shivam was not having a great time in Belfast either. He felt lonely and stuck in a mostly white city and had hardly encountered any international students.

Before coming to the UK, Shivam was an optimistic, kind and hardworking individual who was liked by his peers and co-workers anywhere he worked. With negativity around him, he felt his attitude and motivation change with each day he went to his university.

“I felt left out in my university which mostly had locals or Europeans with a very small number of coloured people. My flat had four home students other than me who were not very welcoming either. It felt like they did not expect many international students to enrol this year,” he said.

Shivam got along with his classmate, Ze who was from China and was friendly with a Turkish international student in his student accommodation. He and Adem bonded over their common experiences in the city and having a smoke every night before going to bed.

“Despite being an extrovert, I stopped trying to make friends after realising everyone’s common attitude towards outsiders in the city,” he said. “There weren’t many South Asians around and Belfast did not have many Indian cultural associations that I knew of which made me isolated from my culture as well.”

After gaining some mental health support, I soon started taking anti-depressants and tried my hand at cannabis

Shivam Shah

In diverse cities like London, Birmingham, and Leicester, each with over 6% of its population as Indians, an international student from India would find ways to their people and find ways to connect with their culture. However, Belfast has minimal Indian influence with only 0.5% of its population being from India.

Shivam took a few trips to London and Birmingham with his friend Adem to break away from the routine of their lives in Belfast. Though he got some respite from the monotony by visiting various Indian neighbourhoods and social hubs, he found himself sinking deep into a depressive pit.

“After gaining some mental health support, I soon started taking anti-depressants and tried my hand at cannabis with my flatmates one evening which soon got me almost dependent on them,” he recalled.

His depression made him detached from his family and friends back home, with his addictions adversely affecting his appetite and well-being. “I was just productive enough to complete all my coursework and submit them on deadline. Otherwise, I was simply smoking and meeting my Turkish friend for drinks on the weekends,” said Shivam.

Following the second incident at the bus station, he was unable to concentrate on his assignments or chores and was desperate to go back home for the summer but felt stuck in his condition.

Pallavi Bose, an employee at an overseas education guide group that aids students in applying to universities abroad and helps them through the process, shared insights about students who come back to India following their education instead of pursuing a Graduate Visa.

“Students normally have very distinct experiences in different parts of the UK with many facing challenges unlike others like racism and other forms of discrimination. It often discourages them from continuing in the UK to find jobs after facing repeated rejections,” she said. “They prefer coming back to India and finding jobs in their fields instead of trying hard to get one in the UK which they consider increasingly competitive.”

“I could not earn much of a side income as I was unable to get a part-time job during my term time. Most places refused to hire me and some that did want to have a very low wage,” Shivam said. “I feel ashamed to ask my parents for money as I have been so out of touch with them in the past year.”

A bright, hopeful Shivam had come to the UK with aspirations and goals of excelling in his master’s degree and making a life for himself away from home. However, his homesickness has made him decide to go home as soon as he finishes his degree.

“I miss my family and the warmth of my house for a long time and want to go back to India to get away from the negativity I have faced all this while. I hope to come back and visit a better side of the UK next time,” he said.