A long time ago fossil fuels were seen as wonderful, but this whole time they have been slowly killing us – what is going to happen?

We are falling blindly and headlong into a chasm which may already be impossible to escape. Climate experts and activists have been screaming into deaf ears for well over half a century about impending disaster. The evocative image of society teetering on a cliff’s edge has been an effective metaphor signifying the danger humans face, but at this point the metaphor is outdated. The cliff is gone.

For a long time, at least since the turn of the 21st century up until fairly recently, the concept of climate change has been up for debate. Is the climate really changing? Are the effects severe enough to change human society irrevocably? Is there anything we can do to stop it? Experts – scientists who have dedicated their lives to studying this exact topic – would tell you the answer to all three questions is a resounding “YES”. The climate is changing, the effects will be disastrous, and we can still mitigate the worst effects.

Unfortunately for the human race, plenty of mistakes on climate change have been made, both malicious and unintended. The BBC has always attempted to appear impartial and trustworthy, but this has led them to make bad decisions in this regard. Platforming climate change deniers against experts is no more impartial than a debate between a scientist and a believer in the flat earth conspiracy, or a genocide denier and a historian. Platforming two opposing ideas gives massive credence to both, which is fine when there is legitimacy to both but potentially harmful when one idea is ridiculous, unprovable, or dangerous.

Of course, there has also been a significant and malicious effort to downplay and deny the effect that burning fossil fuels is having on the environment. Massively wealthy oil companies like ExxonMobil have an obvious incentive – if fossil fuels are destroying the planet, what will that do to their stock prices? Since at least the 1980s, ExxonMobil and other companies have used their massive power, connections, and coffers to fund and propagate climate denialism. Millions were spent on ‘thinktanks’ whose sole purpose was to create seeds of doubt in the general public about the reality of climate change. If you’ve ever considered ideas such as “If the climate is getting warmer, then why is it so cold?” then you have been influenced by these thinktanks, even if you didn’t realise.

This serves to influence public opinion on environmental issues – climate spending seen as frivolous, protesters and activists seen as unwashed hippies. In turn, this influences the policies presented by political parties, and therefore the policies available for the public to vote for. ExxonMobil also had a unique access to the Bush presidency (2000-2008) which allowed them to influence American climate policy massively and directly for almost a decade. President Bush chose to withdraw from the Kyoto protocol, a worldwide treaty which asked signatory nations to attempt to reduce their carbon emissions, almost immediately after entering office. A 2007 report put together by “A Union of Concerned Scientists” called ‘Smoke, Mirrors, and Hot Air’ compared Exxon’s tactics to those used by tobacco companies trying to deny a link between smoking and cancer.

Degrees of Warming

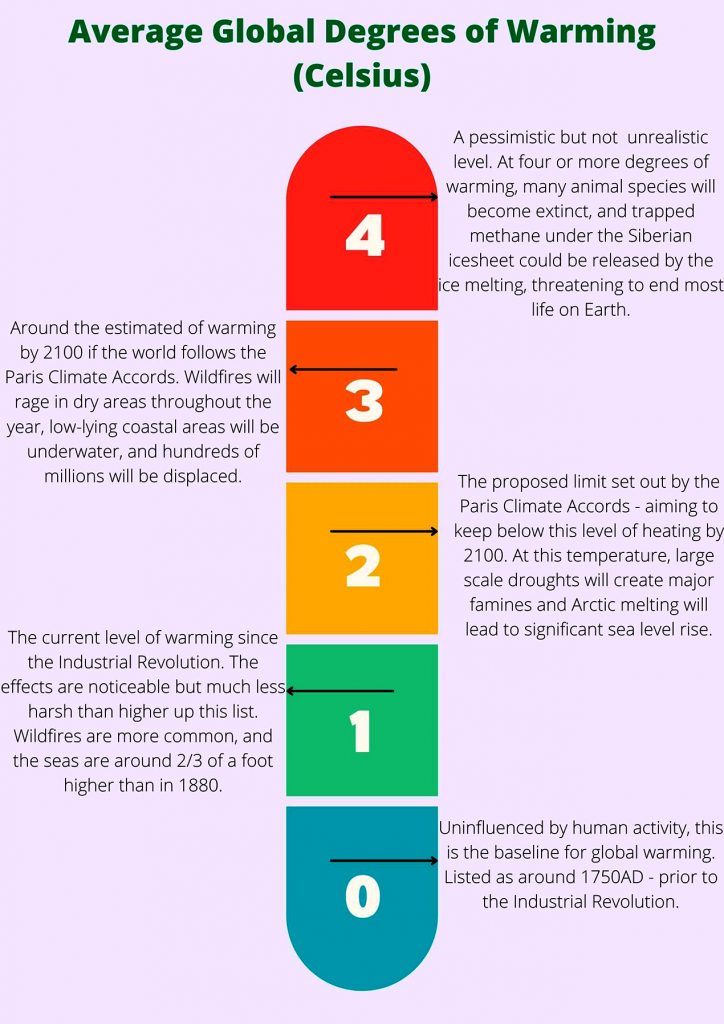

So okay, we know climate change is happening, and we know there has been a concerted effort to hide this from the public. But how bad can it be, really? Scientists assess and predict the effects of climate change based on a model of ‘degrees of warming’. Put simply, for every degree Celsius or so of average warming, the Earth will experience harsher and harsher climate conditions. Although this model works well in academic circles, it may have given credence to the idea that climate change is a minor problem – warming of one or even two degrees Celsius does not sound that bad to someone unfamiliar with climate science. The truth is, even just a couple of degrees of warming will be catastrophic, and we’re on course for far more.

Prior to the 19th century, the effect humans had on the environment was fairly negligible. Although fossil fuels were burned, the scale was insignificant compared to post-industrialisation. Great Britain first started using coal on an industrial scale sometime around 1770, with most of Europe and the USA following the trend soon after. In the two centuries or so since the industrial revolution, the Earth has seen around a degree of warming, and with that has come fairly significant consequences. The sea has risen roughly eight inches globally since 1880. While this may not seem much, for low lying countries like the Netherlands, Bangladesh, and flat islands, this is devastating. Farmland near the coast or on rivers becomes inundated with seawater, killing crops and destroying homes. If global emissions dropped to zero now, we would still see at least another 1.2 to 2.6 feet or more of rising. Millions if not billions of people live in areas at risk from flooding already, and more warming will only make this issue increasingly grave as the 21st century progresses. Rising seas aside, the sheer temperature increase is incredibly dangerous – the degree of warming is not distributed equally across the planet. Humid areas such as in Southeast Asia and elsewhere around the tropics have seen massive increases in temperatures which can make it dangerous to work during the day.

That’s just one degree. What if it was more? The Paris Climate Accords, held in 2015, led to an agreement signed by the countries of the world to keep warming down below two degrees Celsius. This would be a relief, except the accords are non-binding and, as demonstrated by former President Trump, there’s nothing to stop a country retroactively refusing to participate. If warming reaches 2 degrees Celsius by 2100, the coldest nights in the Arctic Circle and Antarctica will be as much as ten degrees hotter on average. At this temperature, we will start to see major melting of the polar and Greenland ice sheets, leading to a huge rise in sea levels. Millions of people will suffer from food insecurity, and cities near the equator will start reaching high enough temperatures to kill. This is still an optimistic estimate.

Three degrees. At this point, society as it exists today will be unrecognisable. Droughts will rock the from South America to Europe to Southeast Asia. Seas will inundate the coasts of Bangladesh, the USA, Europe, and elsewhere across the globe, destroying crops and rendering rivers into watercourses devoid of animal life. Wildfires, such as those recently seen in California and Greece, will be much more intense, last much longer, and destroy far more land. Currently, a realistic estimate for our warming by 2100 is around 3.2°C – the likely result if countries keep to the targets listed in the Paris accords.

Beyond this point is little more than violent misery. Damage costs from climate disasters will become unaffordable – people in certain areas will be living in constantly flooded houses, racked by hurricanes. Food will be incredibly difficult to come by, and many millions will die of hunger or thirst. At this level of heating, we may begin to see even worse knock-on effects that could end life on Earth entirely. Under the Arctic ice sheets lies a sleeping dragon, and we’re starting to wake it up. At four or five degrees of warming, this dragon is likely to begin stirring. Methane. As a greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide is pretty underwhelming, but methane is a real champion, managing to be around 30 times more efficient at trapping heat in the atmosphere. Methane is the reason for Venus’ incredibly high surface temperatures. If the Earth’s temperature increases too much and enough ice is melted, then we will enter a ‘feedback loop’. Essentially, the more we heat, the more methane gets released, the more we heat, the more methane gets released, ad infinitum. This scenario is apocalyptic. If the countries of the world manage to stick to limits set out it may remain out of sight, but we’re already starting to see methane leaking out from deep under Siberia, and many climate models do not sufficiently account for leaked methane.

Healthy Optimism

This does not mean doom and gloom. It certainly is a bleak outlook, but it could always be bleaker. The thing is, we have not reached the point of no return yet. Although we are almost guaranteed between 1.5 and 2 degrees of warming by 2100, it is still possible to keep it at this level and not reach more devastating peaks. There have been significant inroads into generating energy with minimal emissions – wind, solar, geothermal, hydro, and nuclear. These options do have their own problems, but there is huge potential for further development, and none of them have anywhere near the same levels of danger or long-lasting consequences as fossil fuels – even nuclear.

In order to prevent disastrous levels of warming, countries need to strive towards the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 at the latest – if not much, much sooner. This is by no means an unrealistic goal. Costa Rica, a country in Central America, pledged to become carbon neutral by 2021. Currently, the country is powered 99% by renewables. The potential exists for the UK and many other developed nations to become carbon neutral long before 2050. At the moment, the only thing lacking is the political will to make the necessary changes to the economy.

Norway is another massively renewable country, being the largest producer of hydropower in Europe. Its hydropower sector is 90% publicly owned. While privately owned corporations like ExxonMobil are allowed to run roughshod over the environment with little to no consequences, climate change cannot be stopped. The harsh reality is that unless capitalist nations are willing to harshly punish climate crimes – lying about emissions, funding climate denialism, soliciting bribes to politicians – the system of capitalism is unable to take the steps necessary to limit warming. In a world where short term profit and growth wins out over long term stability, renewable energy cannot ever hope to compete against the infinite wealth and influence of fossil fuel companies.

A carbon tax is a popular policy designed to help people lower emissions, by artificially increasing prices on goods and services which cause CO2 emissions. This is a fairly effective policy, but it has pretty major drawbacks too. Terry Thomas, a published environmental scientist currently working on his master’s degree at the University of East Anglia, said: “You’re meant to use that money to subsidise greener products or invest in insulation, but it’s hard to implement without discriminating against poor people, since it’s a flat tax.”

The unfortunate reality is, we’ve created a world addicted to oil. We need it for transport, for industry, for power – every facet of society is entirely reliant on fossil fuels to function. Even with a carbon tax, people will still drive cars to and from work, because the alternatives such as public transport are currently nowhere near well-funded or effective enough for many people in the suburbs. In this case, all a carbon tax will do is take more cash out of hardworking people’s pockets, widening the already massive rich-poor divide in the UK. Ultimately, a tunnel vision approach to climate policy will not achieve the necessary results, and when we look at the best ways to tackle climate change, we need to be focusing on the impacts these policies will have on the least well off in society. It is possible to craft policy which both reduces carbon emissions and directly improves people’s lives.