More than 100,000 Chinese students are studying in the UK and one in six facing mental health challenges. Is UK doing enough to support the mental health of them?

In 2024, QiQi came from China to study for her master’s degree at SOAS, University of London. She had many expectations for her studies and life abroad, but just two weeks after arriving in London, she encountered a violent incident on the street. This experience had a negative impact on her mental health.

After experiencing the violence, QiQi began to feel fear about starting her life in London. She already had some mental health problems in China, and this incident made her situation worse, causing her life to become unstable.

“I did not expect to experience racism from someone in the second week after arriving in the UK. The person hit me and told me to go back to China. After the incident, I went home and cried. I became afraid to go outside, feeling that anyone on the street could suddenly attack me. I had to take a deep breath every time I left my room,” says QiQi.

QiQi decided to seek help from the university, as she realized that her mental health problems had become serious. She contacted the university well-being service and also used the NHS online consultation. QiQi’ s experience is not unique. In UK universities, many students seek help from the university because of mental health problems. In the 2020/2021 academic year, nearly 210,000 students sought mental health support at UK universities, with an average of 2,032 students per university, according to a report in The Telegraph.

Meanwhile, the number of students with mental health problems continues to increase in UK universities. Michael Sanders, professor of public policy at the Policy Institute, King’ s College London, expressed this view in an article in 2023. “Using a large dataset, collected over a long period, we are able to shine a light on a troubling trend of undergraduate mental health challenges almost tripling in the last seven years,” he says.

Among these students, the proportion of international students experiencing mental health challenges is relatively high, especially Chinese students. In the 2021/22 academic year, Chinese students made up 25% of international students in the UK, and this proportion is expected to reach 70% by 2030, according to a report by the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi).

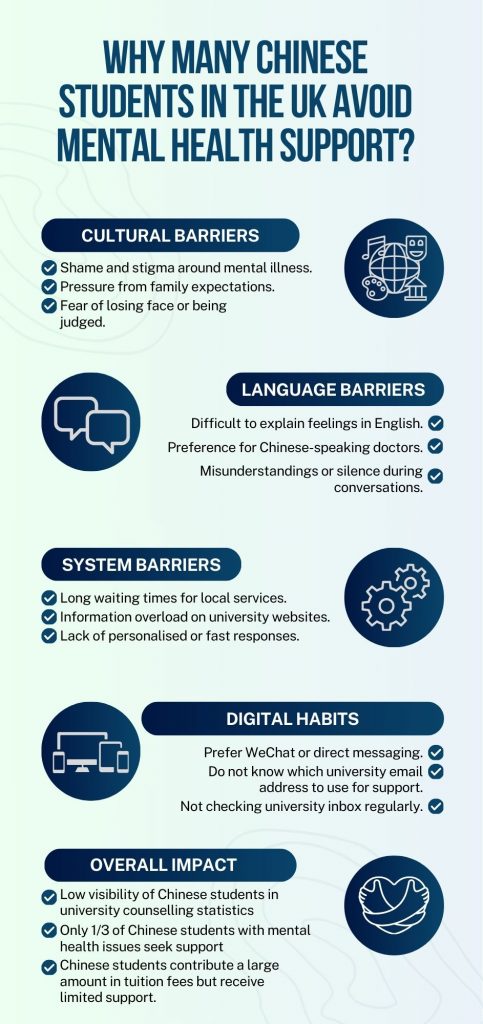

However, despite their large numbers, Chinese students in the UK are less likely to seek formal mental health support compared to local students, according to a study by the National Institute for Health Research.

Data from the UK government also shows that in the 2022/23 financial year, Chinese people used NHS mental health, learning disability and autism services at a rate of 1,883 per 100,000. This shows the overall use of mental health services among Chinese people is low.

This trend is also reflected in the experience of individual Chinese students. “One of my Chinese classmates has schizophrenia. During the university welcome week, we saw a registration desk for the counseling service. He did not dare to register his situation because he felt ashamed, as the registration was in a public place and everyone could see,” says QiQi.

Chinese students make up a large part of the UK university population, but their use of mental health support services remains low. The UK needs to provide more help to address their mental health needs.

A paper by the Hepi points out that Chinese students who come to the UK for study face serious challenges, and UK universities must provide more help for them. Even some Chinese students feel that they are treated as a source of income rather than as valued members of the community, according to Hepi.

These findings are reflected in individual cases. QiQi received a response from the university well-being service soon after she first sought help, and her request for counseling was accepted. However, she felt that the support provided by the staff did not play a major role in easing her mental health problems.

“I think the university staff did not seem trained to deal with cases where foreign students experienced physical violence, but I could see that they were trying to help me,” says QiQi. “Although the first consultation was a disappointment, I later registered my situation with the well-being service, and they have been providing long-term support for me.”

QiQi also contacted the NHS phone consultation. After a long registration process and waiting for a response, she received the phone consultation with local doctors.

“Although I felt that the NHS doctors were willing to help me, I thought they acted more as listeners, while I hoped my problems could be addressed in a practical way rather than only through verbal responses,” says QiQi.

Other Chinese students also face delays and difficulties in accessing mental health support. Ian, a Chinese student from the University of Birmingham. He waited a long time for a response while trying to contact a local GP.

“I was not satisfied with the GP because it took more than a month from registration to receiving support, and the waiting time was too long for me,” says Ian.

The difficulties of seeking mental health support are not only seen in delays for in-person services, they are also seen in problems of finding information and using online services for Chinese students.

QiQi was confused about the updates of the university mental health service websites. When she searched online for the registration page of her university’s mental health service, she found some old websites that were no longer in use, which made it difficult for her to find the correct entry.

“When I tried to register my mental health problems, I found it hard to find the correct webpage. I found several similar webpages, but when I opened them, they were not in use,” says QiQi.

The confusion is not only caused by outdated online information. Even when UK universities provide a large amount of information during welcome week, including details about mental health support, some Chinese students still find it unclear. This point of view was mentioned by Dr. Erla Magnusdottir, who previously worked at King’ s College London.

Dr. Magnusdottir believes that giving Chinese students too much information during welcome week can make them feel overwhelmed and confused, and they may not remember much of it, because they have just arrived and have many other things to deal with.

“I remember talking to Chinese students who found orientation week exhausting. They had just arrived, were given a large amount of information, and were trying to sort out practical matters like where to live and how to get to campus,” she says.

To help Chinese students access accurate information and understand each step of the mental health support services, UK universities should provide Chinese-language sessions during welcome week. This suggestion was also mentioned by Dr. Magnusdottir.

“You can’t just check a box and say, oh, I gave them all the mental health information during orientation week,” says Dr. Magnusdottir. “There should probably be sessions during orientation in Chinese because the group is large enough. These sessions should be conducted in a culturally appropriate way. I think this is something simple for universities to do, and it is not very costly compared to the amount of funding that this large group of students brings in.”

There is a gap between the economic contribution of Chinese students in the UK and the support they receive. Chinese students contribute 2.3 billion pounds annually in tuition fees to the UK’s higher education sector, yet they continue to receive inadequate support from UK universities, according to a report by The Guardian.

Many higher education institutions have made progress in developing mental health support, but they still face challenges with funding, according to a report published by the UK government.

A record number of universities are in deficit. In the 2023/2024 academic year, 61 out of 143 higher education institutions reported a deficit. according to an analysis by The Telegraph.

This financial pressure has led to cuts in staff and services, and universities have to do this. Vivienne Stern, the chief executive of Universities UK, expressed this view in the analysis.

In the 2023/2024 year, UK universities recorded the highest number of staff cuts, with 10,223 staff members laid off across 108 universities, universities were required to pay 210 million pounds in severance costs, almost double the amount of the previous year, according to The Telegraph. “The reality for most universities is that they have had to make serious cuts,” says Vivienne Stern.

Financial cuts explain some of the gaps in support. But even where services exist, cultural barriers often stop Chinese students from using them.

For many Chinese students, mental health is still a private thing. People do not talk about it at home, and they feel even more uncomfortable talking to strangers. “Chinese people often feel shame about their mental health problems, we usually do not want to talk about these things with others,” says QiQi. “I took a gap year to treat my mental illness, but I would rather tell others that I spent the year traveling than say I was receiving treatment.”

A study by the National Institute for Health Research found that Chinese students in the UK do not often use formal mental health services and prefer to ask friends for help when they have problems.

This was also evident in the experience of Lingjia Zhong, a law student at the University of Bristol. “I know there is counseling through the GP, but I never applied. Most of the time I just try to deal with it by myself,” she says.

Instead of turning to official services, Zhong often relied on informal methods. “When I feel low, I might look at posts on Chinese social media or read things I wrote before to comfort myself. Slowly I can sort it out on my own,” she says.

These cultural barriers mean that many Chinese students do not access the support that is available. This gap raises the question of how universities can make their services more approachable. “I think universities need to do better at making sure they have counselors who speak Chinese and provide materials in Chinese. Students are often tired after using English all day, so if the information pamphlet is not in their first language, they are not going to read it,” says Dr. Magnusdottir.

QiQi agreed that language is a key barrier. She would feel more comfortable if there were Chinese-speaking counselors available. “If the university had Chinese-speaking staff, I would be more willing to seek help. I would not have to worry about my English or spend time explaining my situation,” she says.

For Lingjia Zhong, the problem is not only about language, but also about cultural understanding. “If universities had Chinese services, I would be more willing to go. Using my own language makes me feel safer, and someone with a similar background can better understand what I mean,” she says.

While cultural barriers remain a key issue for Chinese students, many UK universities have increased their mental health budgets in recent years to respond to rising demand.

In the past five years, the average spending on mental health services has gone up by 73%. Some universities, such as Greenwich University, have raised their budgets by almost 600% to meet the rising demand, according to an article from The Times.

The pandemic also caused serious disruption to the education and personal development of young people. As a result, many university students are reporting mental health and wellbeing problems. The rising level of demand needs more government funding, especially as many UK universities are under financial pressure. Professor Sasha Roseneil, vice-chancellor of Sussex University, expressed this view in the article.

These improvements show that UK universities are becoming more aware of the seriousness of students’ mental health problems. But for Chinese students, the services that are available may still not be enough. As Dr. Magnusdottir says:

“Chinese students are such a large group in UK universities, so they need stronger support. I think the current structures are failing Chinese international students on that front, so universities probably need to put in a bit more effort than they do with home students.”