As awareness grows about the low participation of women in chess, England Women’s Coach Lorin D’Costa discusses their development in the UK. What key challenges must be overcome to inspire more girls to get in touch with the game?

A young Italian girl sat across the board, her eyes focused on the pieces, blocking out everything around her. Lorin D’Costa, her opponent, couldn’t help but admire her skill and focus as she played under the pressure of so many watching eyes.

This happened in 2019, at a major European chess tournament in Germany with nearly 2,000 players. In the fifth game, Lorin faced this 21-year-old player, who quickly became the center of attention. He was amazed at her concentration, even though he was used to playing in big events.

“But then I thought after the game, should she have to be used to this?” Lorin says. “Is it fair that she has so many men watching her, but I don’t have anyone to distract me? Is this just part of being a woman in chess—or in other areas of life? Is that good or bad for me or her? I don’t know.”

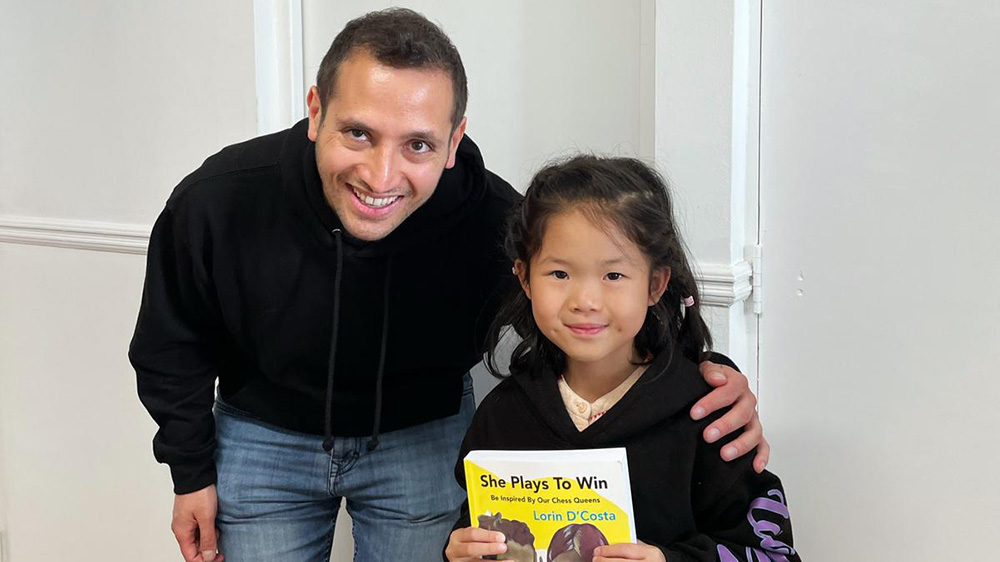

Lorin has long been involved in the world of competitive chess. Beyond his own success as a player, he founded She Plays To Win (SPTW), an organization that focuses on providing more opportunities for girls to learn and compete in chess, aiming to address the gender imbalance in the sport.

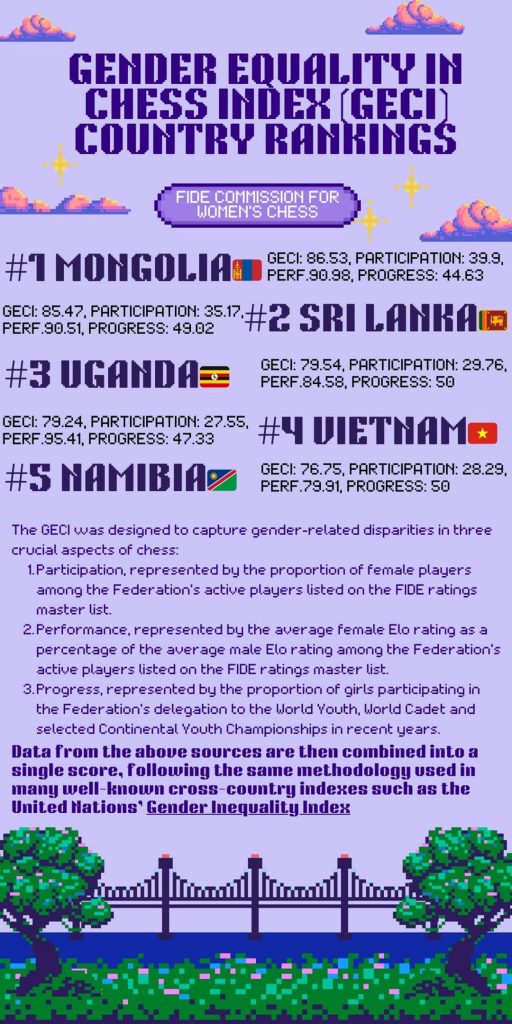

Female participation in chess across Europe, including England, was approximately 7%, according to the European Chess Union in 2019. Apart from countries with a strong chess culture, such as Georgia, Russia and Poland, where they are really pushing chess, most other nations are believed to have similar rates.

A wide range of attitudes towards female chess players over the years encountered by Lorin. While these views often depend on the individual, some comments still stand out and worth paying attention to.

One incident that happened while he was coaching young players in Austria during the European Championships with the English kids. A 9-year-old boy stated, “I think I should always beat girls because girls are stupid, so I should win.” However, he had lost more games against girls than the boys.

“The story is from a long time ago,” Lorin recalls, “but it still was quite shocking to hear it.”

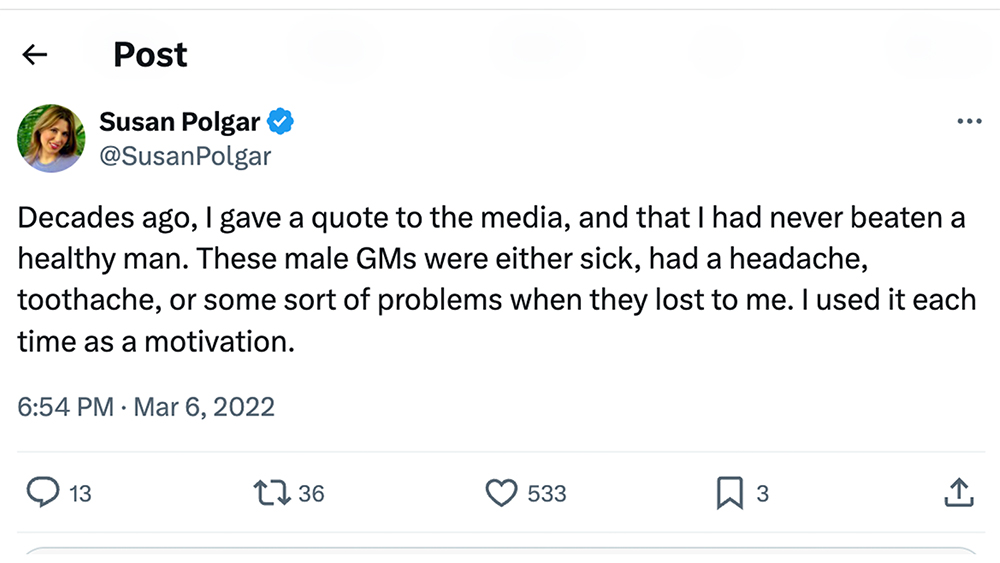

Another example comes from Susan Polgar, one of the greatest female chess players in history. “I had never beaten a healthy man,” she said. Whenever she beat a top player, he always complained of a headache or he was ill or something, because he didn’t want to say that he lost the woman.

“These attitudes maybe are old, and I think that’s probably something you have to ask the girls,” says Lorin. “But I think more a case of this, we just have too few women play. That’s the thing.”

“As a manager, the kind of comment or attitude is a shame,” he says. “Girls should just want to play chess for the love of the game, but instead, they have to play and put up with comments that fit what people expect to hear.”

With deep insights into the unfair treatment and disparity in numbers faced by women in chess, Lorin reflects on how societal pressures influence their participation both on and off the board.

That’s maybe a societal problem rather than just a chess problem.

Lorin D’Costa

As an International Master who plays for England, it wasn’t until he competed in the 2004 World Under 20 Championships in Cochin, India, that he realized there were no English girls being sent to the tournament—because they didn’t even have one.

In hindsight, he attributes this lack of representation to the fact that most girls tend to stop playing chess around the age of 12, during secondary school.

Top players rarely come from girls who give up chess at a young age. “So that’s mostly what we’re trying to do here–to get more girls aged 5-9 to get into chess and stay into chess, to create this community where they can compete with each other,” says Lorin.

This has also become the core challenge SPTW seeks to address: How can they encourage girls not only to start playing chess but to continue as they grow older, particularly past the age of 12?

Yet, despite the obstacles, Lorin is hopeful. “But attitudes are changing,” he says. “Nowadays, these comments are fewer and fewer.”

For decades, Lorin has always shown respect to the opponents he’s encountered. When they sit down to chat, many are willing to open up about their experiences in the game, offering insights into both highs and lows of their journeys.

The stories of women like Antoaneta Stefanova, the 2004 Women’s World Chess Champion, remind us how far we’ve come—and how far we still have to go. During their dinner together, Antoaneta reflected on her own experiences in the chess community, sharing the difficulties she had faced along the way.

“The young girls now, they don’t know how bad it was for me in the 1990s,” Antoaneta said. Lorin asked, “It’s still bad, right?”

“Yes,” she admitted, “but it was much worse for me because I was the only girl.” She was about 18 at the time, and the challenges felt overwhelming. Antoaneta described her situation as “sink or swim”.

Her determination stood out as she pushed through the challenges of a male-dominated environment. She ultimately decided, “Either I quite or I really want to play chess, and I just dealt with it.”

Now in her 40s, Antoaneta acknowledges, “Look, I helped make it better, but there’s still more we can do.” “It’s sad that these things happened,” Lorin agrees, “but hopefully, they can be changed. We can improve every we address this kind of attitude.”

While progress has been made, Lorin knows that overcoming these attitudes is only part of the challenge. Beyond the biases, another factor contributing to the gender gap in chess is the social element, especially when it comes to keeping girls engaged after the age of 12.

One of Lorin’s students is highly talented, but chess isn’t her top priority. She’s more interested in other sports and doesn’t feel the drive to commit more time to chess.

Lorin often finds himself competing with her social life. “I’m trying to get her to play chess, but it’s hard when I’m up against her neighborhood friends,” he says.

The problem is, if she attends a chess tournament, she might miss out on social activities. “There are so few girls. They think it’s going to be boring,” Lorin explains. In June, a 13-year-old student hesitated to join a London tournament, then pointed to two other girls and said, “If they go, I’ll go.”

Moments like this remind Lorin how much girls depend on social connections to stay engaged. “If there are only 4 girls and 150 boys at a tournament, that’s not fun for them. But if there are 40 girls, they’re more likely to come.”

Creating that sense of community is a key mission of She Plays To Win. Lorin, as a male coach, does what he can—sending emails to girls and parents, urging them to participate, and building connections.

In August, 15 girls from his program travelled to Barcelona for a tournament. “I pushed hard for this,” Lorin says. He thought about more than just the chess—where they would stay, how they could socialize, if they’d have time to explore the city and enjoy themselves as a group.

Lorin’s dedication goes beyond teaching chess. He’s working to create a supportive community where girls can thrive, both on and off the board.

Two years ago, while browsing the English Chess Federation (ECF) website, Lorin stumbles upon an omission. Under the “communities” section at the top, it listed junior, senior, international, and other categories—but there was no stage for women’s chess.

Lorin was taken aback. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute, all these girls are learning from me and She Plays To Win, but the national body ECF, they don’t have a page,’” he recalls. For a coach dedicating his career to promoting girls in chess, this is a stark reminder of the visibility challenges women face in the game.

Without hesitation, he sent an email to the ECF. “I know a lot of people there,” Lorin explains, “so I said, ‘You don’t even have a page on your own website. How can I possibly tell the girls to sign up to English Chess Federation?’”

Remarkably, within a week, the ECF staff responded. They had rectified the issue, and now a dedicated women’s chess page was live. It obviously was a small but significant victory. The ECF is clearly working hard to improve. They regularly hold women’s tournaments, with recently one scheduled at the end of August.

The website lists a Director of Women’s Chess, who has been dedicated to organizing these events and, over the past three years, has consistently pushed for funding. “What we can see is everything is improving, but still a little lonely,” Lorin acknowledges. Moments like this show there’s always more to be done.

That’s where She Plays To Win comes in. The organization is focused on promoting girls’ chess across different age groups, supporting girls and young women in primary school, secondary school, and universities up to the age of 28.

Now, SPTW has about 1,500 girls on their list from across the UK, representing a wide range of ages and experience levels. Chess offers more than just competition—it builds strategic thinking, resilience, and confidence.

For young girls, there are not just game skills; they are life skills. Learning to think ahead, make calculated decisions, and adapt to changing circumstances helps girls develop mindset that will serve them in any career they pursue.

It also teaches them how to handle both victories and setbacks with grace, lessons that extend far beyond the chessboard. As stated on the SPTW website, “It’s time to give more girls the best possible opening move in life.”

Since the launch of SPTW, five English girls have become Women FIDE Master, which is the first title for chess. “What’s happening is some girls are achieving this, and other girls are saying, ‘We want to do it too,’” Lorin explains. “One of the ways we can grow is by girls inspiring other girls to do it.”

A young girl who joined the very first online lesson SPTW held. In just four years, she became a FIDE Master, and today she ranks in the top five in the world for girls under 12, with a current rating of 2,118.

“She is very social,” Lorin says, “We gave her the opportunity to play on the squad and meet other girls.” This connection has been key—not only in forming friendships but also in helping her develop her chess skills.

Lorin is quick to point out that, while SPTW played a role, her success is ultimately driven by her own determination. “We’re just a small part of it. We cannot claim the success of it. But even if it’s very small, I’m happy to say it was a small piece of the celebration,” he says.

It was her self-motivation that truly propelled her to where she is today. “She’s really created a good friendship, but also the chess aspect has really helped her grow,” Lorin adds.

Despite the successes, SPTW still faces challenges when it comes to reaching more girls and keeping existing members engaged. “We’re still a long way from reaching out,” Lorin admits. “But we don’t have budget for advertising.”

To keep the community informed and engaged, SPTW sends out monthly emails, updating members on what’s happening within the organization. “Every month, we write to them about what we’re doing,” Lorin says.

This September, they plan to introduce a reform, including a detailed calendar of events. Additionally, the SPTW website features a dedicated “Join” page, making it easy for new members to sign up and become part of the growing chess community.

Looking to the future, Lorin envisions a chess world with true gender equality with 50% men and 50% women. But with current female participation hovering around 7%, he acknowledges there’s a long way to go. “So even if we get 35%, 40% women in total, that would be really, really good,” says Lorin.

“Many girls don’t know how to get into it. They’re scared a little bit, whatever, lots of reasons,” Lorin says. His mission is to help break down those barriers, encouraging more girls to give chess a try and, finally, fall in love with the game.

As a coach, Lorin’s advice to girls starting out in chess is simple yet profound: believe in yourself and understand that success in chess isn’t about intelligence. “It’s not about whether you’re smart enough, because you are,” he says.

Instead, he emphasized perseverance. “The main thing is how you have some resilience to understand chess, especially in the beginning. You lose—like I lost my first five games when I was nine years old in my first tournament—but I was willing to come back.”

Many girls, Lorin explains, are discouraged after a negative first experience. “A lot of girls tell me, ‘If I have a very negative experience the first time, I don’t want to go again.’” That’s something SPTW is actively working to address. “The first time they play in a tournament, then we will keep them in, and then they will get good.”

His key message is about believing in themselves, especially when things are tough. “They have to stay strong and realize that with chess, you don’t always win or you hardly ever win at the beginning,” Lorin says.

“It’s a learning process, chess is a tough game—that’s the beauty of it. You have to face challenges, play with more experienced players, and even lose. But what did you learn? How are you improving for the next time?”

In a video featured on the She Plays to Win website, several girls share why chess has been so beneficial to them. “Chess has helped me achieve,” one girl says. Another adds, “Chess helps me learn sportsmanship, and I found it really fun because I like thinking logically.”

For others, the impact goes beyond the game. “Chess helped me become a more confident person,” one girl shares. Another explains, “Chess helped me to think ahead.”

One of the girls sums up her experience by saying, “Chess has taught me to overcome failure, learn from my mistakes, and it’s allowed me to travel the world and make connections with lots of people.”

In chess, when a pawn reaches the end of the board, it could be promoted to a queen. Similarly, girls could achieve their unlimited potential through chess.

With persistence and the right support, more girls will not only enter the world of chess but also excel in it. The future of chess is bright, and women are an essential part of it. “Stay strong, understand that becoming good at chess takes time, and you’ll learn to love and enjoy the game.”