Dark tourism is becoming a worldwide phenomenon. Why are people attracted to travelling to places associated with death and disaster?

It was a cold, dewy September morning as Takemi Tan waded through the thicket of the infamous Aokigahara Forest near Mt. Fuji in Japan. Also known as the Sea of Trees or the Suicide Forest, she could barely catch the sunrise, as little light penetrated the forest floor through the thick green canopy above.

Despite the forest’s lush greenery, she saw no animals and heard no birds or insects. The eerie silence was so profound that it felt like the forest was breathing with her. As she walked past signs that said “Do Not Enter”, her eyes fell on a branch, and she froze.

“It was just there—two legs suspended in the air. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. A body was hanging from one of the branches. I am still not sure if it was a man or a woman. It’s an image that will stay with me,” said Mrs Tan.

This incident happened in 2010, the same year over 54 bodies were recovered by authorities from the forest. Between 2013 and 2015, more than 100 suicides were committed in Aokigahara Forest, according to CNN. The Japanese government no longer provides statistics on suicides in the forest. Given Aokigahara’s reputation, why did Mrs Tan still visit it?

“That’s the thing. Despite being known as a suicide forest, it is a wonderful green sanctuary right next to the holy Mt. Fuji. The entire experience itself was very relaxing. After the incident, I visited the place four more times and luckily never encountered more bodies”, said Mrs Tan laughing.

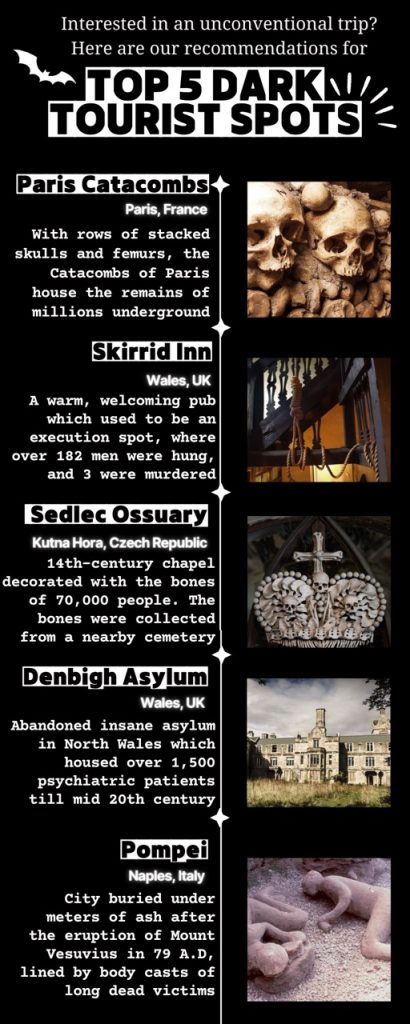

Finding dead bodies did not stop Mrs Tan from exploring Aokigahara Forest, and she is not alone. In her own words, she finds fun in travelling to places associated with the eerie. This type of tourism is called dark tourism or thanatourism. The term, originally coined in 1996 by academics J. John Lennon and Malcolm Foley is defined as visiting and experiencing places where death and disaster have occurred. Examples include the Cambodian Killing Fields, the fire mummies of the Philippines, and Nazi concentration camps.

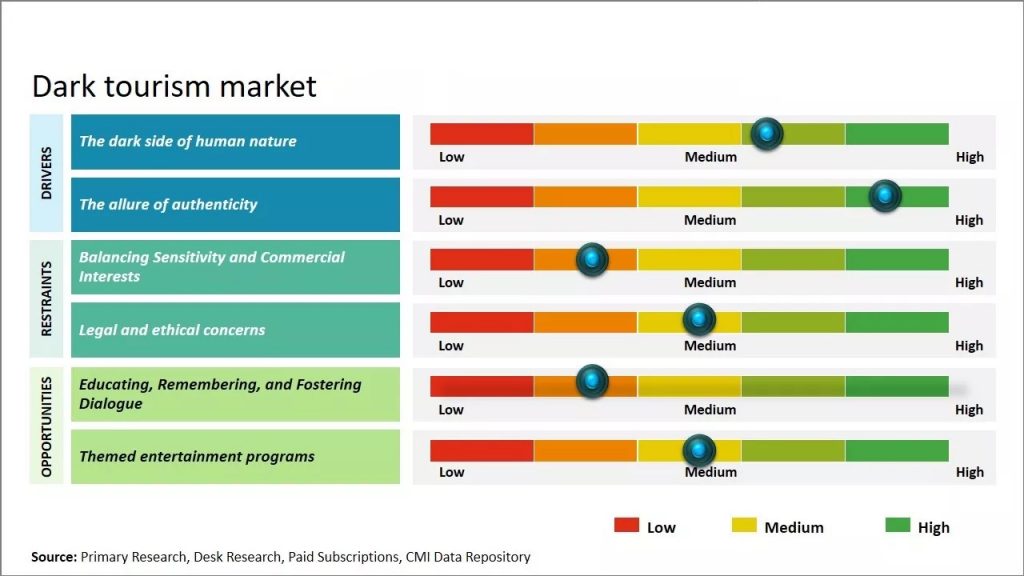

According to research published in Digital Journal, the global dark tourism market is set to reach $43.5 billion by 2031. A significant demographic contributing to its rise in popularity is Generation Z, those born after 2000. In a 2022 survey by Travel News, 91% of Gen Z respondents reported engaging in some form of dark tourism. Amidst the growing market, an important question arises: What attracts people to sites associated with death and darkness?

Dr Peter Magano, a professor of tourism management at London Metropolitan University says, “There is darkness within all of us. When we witness an accident on the road, don’t most of us unintentionally slow down to catch a glimpse? The human psyche is drawn to sites connected with mortality and dark tourism provides that.”

This sentiment is echoed by Enrique Barratt, a software developer based in Cardiff who has been travelling since his university days. After turning 40 five years ago, he decided he was done with visiting the usual tourist spots, and this led him to the allure of dark tourism.

“I have been solo travelling and backpacking across countries for over three decades now, and my favourite and most exciting travel story is still my trip to Indonesia, witnessing locals dressing their dead relatives in an afterlife ritual,” he says.

Image credits: Reddit

Enrique described the Manene ritual on Indonesia’s Sulawesi island, where hundreds of corpses are exhumed and dressed in the village of Torea. This ritual honours the spirits and provides offerings. After opening the grave chamber and cleaning the area, the bodies are dried under the sun before their clothes are changed. “One family even adorned the corpse of their grandfather with a bucket hat, sunglasses, and a cigarette,” says Enrique.

Dark tourism might be the latest catchphrase, but the concept isn’t new. Our fascination with death and murder has existed since the beginning of time. When death, especially by violent means was a common occurrence, it was also considered acceptable as a form of entertainment.

Over 2000 years ago, Romans, famous for killing those who opposed them, celebrated victories with the deaths of their enemies. They also frequently brought slaves and paraded them in front of cheering crowds. Gladiators, who could be slaves, criminals, or even volunteers, would fight each other (and sometimes wild animals) to death in large arenas like the Colosseum. The audience travelling from far and wide would cheer and jeer, and the winner’s fate would often depend on their approval.

Associate Professor Akira Ide of Kanazawa University, Japan, a pioneer in the study of dark tourism, emphasises its many advantages. Visiting dark tourist sites allows us to confront past tragedies and understand the lessons they hold. This reflection can help us make better choices in the future. Such experiences can prompt us to re-evaluate our own values and way of life. By encountering different perspectives on hardship and suffering, we gain a broader understanding of the world. It is important, he notes, to support these efforts economically through tourism and to link the lessons of the past to the future.

Tourist fascination with death is not new to the UK. When Pan Am Flight 103 crashed in Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988, the tourism impact was immediate. The day after the crash, newspapers reported a six- to seven-mile traffic jam on the main road to Lockerbie. The Automobile Association received over 2,000 inquiries from people asking for the best route to the crash site.

When managed properly, it is possible to monetise this influx of tourists. However, locals, survivors, and victims’ families are important stakeholders whose feelings and opinions must be considered. Some survivors and families believe that a site of death and disaster should not be memorialised, let alone become a tourist attraction. This conflict, where visitors want to know but locals want to forget creates a heritage dissonance or cultural gap.

“The line between visiting these places for entertainment and education and insulting locals is very thin. If not mindful, dark tourism can have serious consequences for those connected to the place,” says Dr Magano. This has caused trouble before, with people crossing the boundary between respect and sightseeing.

In 2015, prominent YouTuber Logan Paul filmed himself discovering the corpse of a suicide victim in Aokigahara Forest and uploaded the footage to his channel. The video gained 6.3 million views within 24 hours of being uploaded. Paul’s depiction of the corpse, which was censored, and his group’s reactions quickly led to significant backlash. He was blacklisted by several sponsors and YouTube nearly banned him from the platform.

While the media has expanded the market for dark tourism, the advent of smartphones and social media has made it feel increasingly exploitative. Those seeking to create engaging content for their followers can easily become insensitive and be accused of lacking respect for the victims of these tragedies.

In 2019, visitors to Auschwitz were encouraged by museum organisers to respect the memory of those affected by the Holocaust. This followed a number of people posing for photographs on the train tracks leading to the concentration camp, recreating scenes of Jewish victims being dragged to the camp.

Media and pop culture have drawn more attention to some of the world’s most intriguing places. A recent example is the success of the Indian movie “Manjummel Boys,” set in the infamous Guna Cave, also known as the Devil’s Kitchen, in Tamil Nadu, India. The cave gained fame as over 50 people disappeared without a trace over the years, with no bodies ever found. The movie is based on the survival story of the only person who managed to escape after falling into the underground, twisted cave.

Following the box office hit of the movie earlier this year, thousands of people flocked to the caves, despite knowing how dangerous they are. Although the entrance to the caves has been sealed shut for public safety, the surge in interest and popularity demonstrates the public’s fascination with places associated with death and disaster.

Dark tourism, if not practiced safely, can have dangerous consequences.

Dr Peter Magano

Dark tourism helps to memorialise tragic events and history and even boosts the local economy. However, it also has negative aspects. “The clout-chasing nature of social media makes it difficult to toe the line between shedding light on the importance of these sites and failing to respect the magnitude of the moment,” says Dr Magano.

The future of responsible dark tourism lies in the hands of both visitors and administrators. Dr Magano says, “The increase in tourists, predominantly Gen Z, to these dark tourist hotspots must be coupled with campaigns urging respect and raising awareness of why these destinations are significant.”

Despite the unconventional nature of dark tourism, travellers like Mrs Tan find ways to create meaningful memories while acknowledging the sombre nature of these destinations. “It pains me to see tourists disrespect these places,” she says. “A true dark tourist understands the importance of respect. Those who don’t are simply insensitive and contribute to negative stereotypes about dark tourism, which can be a thrilling and educational pursuit when done responsibly.”

For those curious about dark tourism, Mrs Tan offers encouraging advice, “If you’re unsure but intrigued, don’t be afraid to try it. Of course, it is not for everyone. But as I say, once you go dark, you can never go back” she said as she laughed.