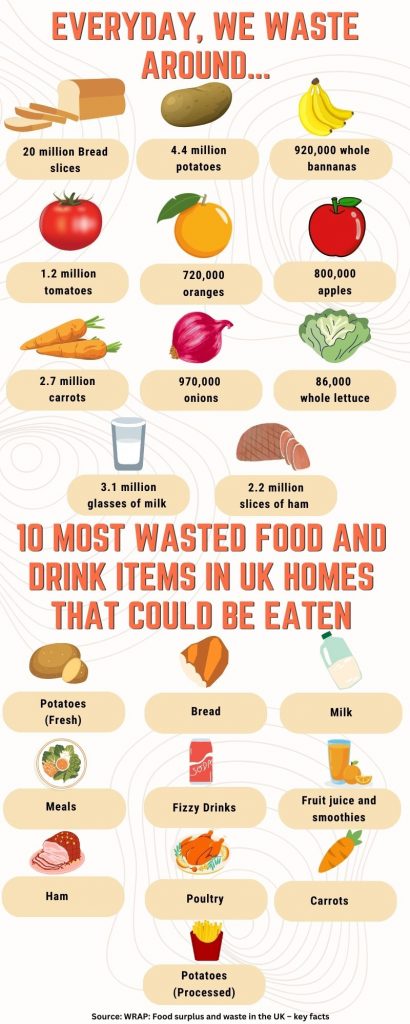

Last year one in four UK children experienced food insecurity while a staggering 3 billion meals worth of food goes to bins each year. Charities are working to rescue this food and make it available to those in need but is it the solution to the country’s food crisis?

It’s the early hours of the day and as the first rays of light brighten the skyline in Brighton a band of trucks docks just outside several supermarkets. As soon as they place themselves in the parking lot crates and pallets upon pallets of avocados, bread, fruits, vegetables, and meat are swiftly taken from the shop and neatly stacked in the back of the vehicle. This is food that could not be sold off supermarket shelves, but is perfectly edible and would go to waste unless rescued.

Once loaded, it is then taken to the Real Junk Food Project Brighton’s central warehouse, where the food will be sorted, weighed and shipped off again to the project’s pay-as-feel shops and cafes. This would save this food from being a part of over 12.9 million tonnes of food wasted annually in the United Kingdom which is enough to produce at least 3 billion meals according to a leading charity. Cafes belonging to the Real Junk Food Project are like any other cafes — bustling with chatters and enveloped in aromatic fragrances from the different delicacies they serve. Paul Loman, one of the Directors of the project says, their business model is anything but ordinary.

“The objective of our business is to drive ourselves out of business by reducing all of the food waste so that there wouldn’t be any,” says Loman. “That’s an ideal view and it will never happen, but our project is a business of increasing awareness that food is available for use.”

The Real Junk Food Project works under the slogan ‘feed bellies not bins’ and rescues food in supermarkets that could not be sold due to any reason but is perfectly edible. This food is then made available to people who need it via their cafes and pay-as-you-feel cafes.

“The global stat is that about a third of the world’s food production goes to waste and there are a lot of people who are hungry who need that food. That was the prime motivation,” says Loman.

Over four-and-a-half million people faced food insecurity by July 2022, recording a rise of 8.8% in the number of households facing food insecurity, according to a leading food charity. Whereas, almost half of the UK population reported buying less food in the first few weeks of July this year, according to official government figures. The Real Junk Food Project uses a donation-based approach to help make its locations more accessible and eliminate the stigma around depending on charities for food.

“We emphasise that people have the right to the food. We’re open to everybody because we ask for donations and we try not to stigmatise people who can’t pay,” says Loman. “It’s very important in the messaging that when people come we say, ‘Are you able to make a donation today’ or ‘Pay what you can’.”

He emphasises that not just stigma, but people are hesitant to avail food from charities like The Real Junk Food Project due to a lack of awareness about the type of food they provide.

“I think the misconception is that some people think we’ve taken it [the food] out of the bin. They think, ‘I don’t want to eat that sort of thing’,” says Loman. “So it’s really about showing people that it’s not like that. That we go to the supermarkets through the front door, this is just food that they, for some reason won’t sell because it’s reached some sort of best-before date, even though in a lot of cases it’s still perfectly edible.

“We get pallets of avocados or whatever, which is just surplus and just given to us. I think they’re quite shocked at how much food there is around that that is available,” he says.

Through several of its pop-up cafes and pay-as-you-feel shops across Brighton, Loman believes the project is changing that perception.

“We principally use surplus food and produce what we like to say is healthy and nutritious meals but we make them available to everybody regardless of their ability to pay. We might have a barista coffee and all the things that you get in a nice cafe,” says Loman. “And we say that everybody should have the right to have that sort of experience regardless of their ability to pay.”

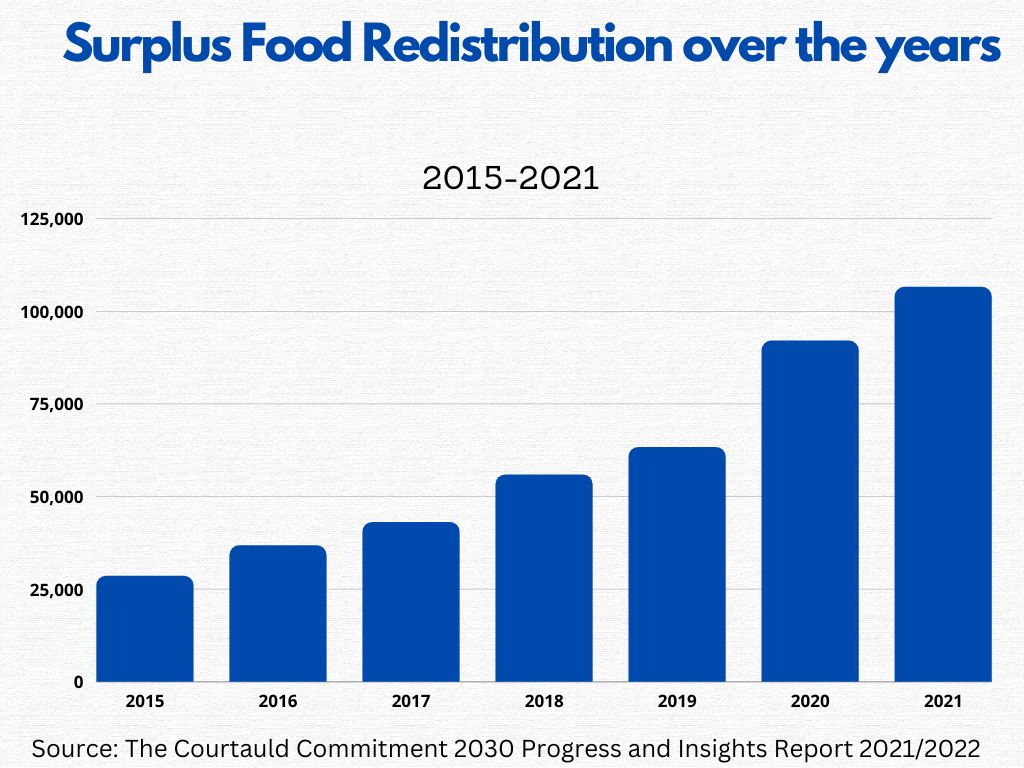

As food prices rose at the fastest rates in 2023, more people were driven to use food banks or charities that redistribute surplus food. Nearly 760,000 people turned to food banks for the first time last year as a record number of 3 million food packages were distributed, according to the largest food bank network in the UK. However, campaigners argue that food banks and charities are not a permanent solution to the country’s growing hunger problem.

Dr Martin Caraher an academic and food policy activist believes food banks and similar surplus food redistribution charities are ‘successful failures’.

He says, “They are successes because they keep growing, but they’re failures because they can’t tackle the real causes of food insecurity. It’s beyond their means. So it’s like sticking plaster on a problem.”

The number of food banks in the country has increased significantly in the last 22 years. Trussell Trust, which operates over half of the food bank in the country opened its first food bank in the year 2000, and by the year 2022, it had over 1400 food banks across the country. In addition to Trussell Trust food banks, there are at least 1,172 independent food banks across the country taking the UK’s total tally to over 2500 food banks.

“In 2000 there were no food banks in the UK, maybe one or two, but there was really no structure,” says Dr Caraher. “Now we’ve got a number of papers talking about food banks or food charity more generally as a third food system. So there is hospitality, retail and now charity food. What it’s done is it’s allowed the supermarkets, some hospitality, to just dump their surplus food on the food bank.”

The Real Junk Food Project Brighton has to separate out around 10% of the food that they receive from supermarkets because supermarkets and hospitality businesses often send them food that is not edible.

“Well, we don’t actually use everything that we’re given because to some extent the supermarkets use us as a bit of a dumping ground. So rather than waste it, they’ll just give us some food that frankly isn’t edible” says Loman. “We do actually end up having to compost it as it’s not edible and we have a responsibility as we’re effectively in the food industry.”

However, not all surplus food redistribution charities have sufficient resources to manage large quantities of surplus food. Dr. Caraher believes that even if all of the surplus food in the food system is made available to such charities and food banks, it would simply overwhelm them.

“They can’t store perishable goods, they can only store dry goods because they haven’t got refrigerators, so they can’t handle them. They’re not registered to handle perishable foods and there’s a whole load of problems like that with the food bank problem,” says Dr Caraher.

He argues that these problems, coupled with limited access to food banks make it hard for people to avail food from them in times of need like the Covid-19 pandemic. Households facing food insecurity in the country increased from 7.6% during Covid-19 to a high of 9.7% during Covid-19. This affected 4.7 million adults and 2.3 million children across the UK, according to a leading surplus food redistribution charity.

“We didn’t actually have a food problem, we had loads of food in the country. We just couldn’t distribute it to people. We couldn’t distribute it through the supermarkets because of lockdown and distancing issues and we didn’t have records of those who were food insecure because the charities didn’t keep those detailed records,” says Dr Caraher. “The other thing that happened with Covid-19 was that many of the charities involved relied on volunteers, and a lot of those volunteers were vulnerable themselves to Covid-19, so they didn’t go to work and the whole system fell apart.”

Still, members of the government have often hailed food banks as the potential solution to the food insecurity crisis from time to time — something that has been repeatedly opposed by activists and experts in the field of food redistribution. Dr. Caraher believes that though food banks provide food to the needy, they cannot be a long-term solution.

“Food banks feed people who are hungry, that’s what they do. They don’t attack the underlying issues of food insecurity because they can’t,” says Dr Caraher. “Members of the government are quite happy to point to food banks as doing all these good things which aren’t tackling the underlying causes of food insecurity.”

“That’s about income, it’s about living conditions, it’s about general inflation and that’s not their (food banks’) role. It can give people skills, it can give people food, but they can’t tackle those underlying conditions,” adds Dr Caraher.

The importance of putting money in people’s hands to alleviate food poverty instead of depending on banks is also reiterated by major food bank networks across the UK.

In response to the Spring Budget 2023, the Chief Executive of Trussell Trust, Emma Revie said, “We remain concerned that social security is not providing people with enough income to afford the essentials. This has been a huge factor in our network having to distribute more than 7,000 emergency food parcels a day this winter. Even after April’s uplift, the standard UC (universal credit) payment will still fall £35 short each week of covering the cost of essentials like food, heating and connectivity.”

The Independent Food Aid Network, which also advocates using a cash-first strategy to combat food insecurity, advises local governments to give adequate, well-publicised, and easily accessible cash payments to people experiencing financial hardship and unable to afford food, rather than having them be dependent on food banks.

Citing the United States as an example, Dr. Caraher explained that this model can work well in economies recovering from a crisis.

“They introduced three stimulus packages, which were essentially cash and their food insecurity rates during Covid decreased so more people were food secure because they were getting cash, not food benefits but cash,” he says. “And they basically used that cash pretty well.

“Particularly mothers use cash very well to feed their families. There’s always some abuse in systems, I’m not saying there isn’t but when you hear ministers talk, you think everybody abuses the system. Actually, the abuse in the system is so small, it’s not even worth talking about,” he says.

Mr Loman too believes though it is crucial to feed people as food insecurity rises, surplus food redistribution only serves as temporary relief.

“It shouldn’t be necessary that people are relying to go to food banks. This is a terrible blight on society, that so many people can’t afford to do their shopping and feed their kids. The charities, or people like ourselves are patching up a system, that’s broken and there needs to be some other more systemic change. I do agree that to some extent we are a plaster on the problem,” says Loman.

“Surplus food is not a solution. I think it’s quite useful and it’s highlighting a particular issue, but it’s not really dealing with the underlying causes of food poverty.”