Already being forced to cope with the demons of Islamophobia within the LGBTQIA+ community, how are queer Muslims juggling their faith and identity at the same time?

As reporter Clark Kent dashes into a telephone booth, hastily removes his glasses and dons a bright red cape, he transforms into Superman and saves the world from rogue villains. While his superhero avatar is enchanting to millions of people, for Deenah-al-Aqsa, this is the story of her life.

A journalist during the day, as soon as the clock strikes past 5, she becomes a queer Muslim activist known only by a voice behind the screen and a photograph with the silhouette of a hijab, which she uses as her display. To Deenah, her identity feels like a double-edged sword where she exists both publicly and anonymously, but the fear of being outed to her family forces her to remain behind the pseudonym.

“My identity is a very private thing, which is how I like to keep it. It can be a bit tricky. If I’m sending invoices, it is going to have my real name on it. I have to add a caveat and say, ‘Can you make sure that it’s kept confidential and isn’t publicised in any way?’ It’s hard, it can expose me. I feel a lot of pressure,” she says, mentioning that she has had to hire out rooms while conducting interviews so that she isn’t overheard by her family members.

Although she has grown up with a strong foundation of religion, she feels that it can be quite tumultuous to have faith when there are both good and bad sides to it. “I feel like it’s my anchor,” she says, adding that sometimes it can hold her down too.

“It can be really hard to find a feeling of stability, but that’s when you need faith or an anchor the most,” says Deenah, whose name is Arabic for ‘principles’. “When the seas are stormy, things are difficult, that’s when I hang on to my faith. But it’s not always an easy journey.”

Despite several shortcomings, she chooses to embrace her religion, such that even when it came to picking a surname, she decided on Al-Aqsa, a mosque in Jerusalem. “The Al-Aqsa Mosque is the third holiest site in Islam, so I chose that,” she says. This was the genesis of the name Deenah-al-Aqsa.

While Deenah’s religious identity mingles with her queer one, this is not the case for many others. More than half of Muslims in the UK believe that being queer is not compatible with Islam, according to a recent survey conducted by Hidayah, an LGBTQIA+ Muslim charity. Many Islamic scholars feel the same way, drawing parallels from holy scriptures where homosexual acts were allegedly condemned by God.

When people look at Muslims, they think about all the things that we’re not allowed to do.

Deenah-al-Aqsa

This very concern has forced them into hiding, or keep their queer identity a secret. A study on gay Catholics found that repressing one’s sexual identity in pursuit of a religious one can lead to severe emotional and mental health issues, especially at a young age.

When Khakan Qureshi, a Diversity Role Model for Stonewall, was younger, he faced difficulties navigating his identity as a gay Muslim who grew up in a religious Pakistani household in Birmingham.

“I couldn’t and wouldn’t express myself because our culture, religion, our community would say that homosexuality was a haram – very much taboo, and you can’t identify in that way,” says Khakan, who eventually moved to London to explore his identity as a British Asian. “I had conflicting thoughts in my mind which led to anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts. It didn’t help.”

Hoping that he would find acceptance within the queer community, he began attending LGBTQIA+ events around London to meet similar-minded people. However, it became difficult when he couldn’t find anyone who bore any resemblance to him.

“I was a brown person in a predominantly white club,” he says. “I just saw one Asian face, one or two other black people, but I didn’t feel welcomed in that space. I didn’t feel that level of acceptance.”

This further escalated during the 9/11 attacks that occurred in the United States, when a war of terror was waged against Muslims around the world, which inevitably seeped into queer spaces. The overwhelming amount of Islamophobia Khakan faced made him step away from calling himself a Muslim.

“It was a label I was really fearful of, simply because of the stigma and prejudice,” says Khakan, who was put in a conflicting position with his sexual and religious identity for over two decades due to these intolerances. “From 1990 to 2000, I navigated being gay, and then being Muslim from 2000 to 2010. It took me a long time to marry the two properly.”

Many like Deenah thus choose to keep both separate. Her identity as a queer activist allows her to actively work for the community, while her real identity lets her practise her faith safely without any barriers.

“So much of my faith is deeply personal, that I don’t broadcast to the world,” she says, mentioning how she often struggles with getting up early for the morning prayer, but doesn’t consider that to be a terrible thing. “I see every time I managed to pray on time as a success.”

She believes that such tactics are necessary to ward off the regressive systems built around religion. “It can dismantle the idea that God only exists to punish people, or that religion is this oppressive, patriarchal tool,” she says. “The structures can be patriarchal, but the individual practice of someone’s faith can be a real source of strength against those structures.”

It takes a lot of work to reach that stage, but having communal support that affirms your queer identity can make it better, according to Deenah. “There’s a lot of mischaracterisation that happens. It requires a community to tell you that you’re not a bad Muslim” she says.

The lack of inclusivity towards Muslims in queer spaces obstructs them from having such conversations. Nearly two-thirds of Muslims don’t feel like they belong in the LGBTQIA+ community due to often being misunderstood or being unable to express their views.

Deenah says that she sticks out like a sore thumb due to her cultural and physical identity, and what people assume of her. “When people look at Muslims, they think about all the things that we’re not allowed to do. That’s what differentiates us from the rest in noticeable waves,” she says.

Another factor that sets her apart is her hijab. Deenah says, “As someone who wears a hijab, it comes from seeing me as representing oppression or restriction, to conflate me with countries that punish homosexuality. I am not those countries, and I shouldn’t be conflated with them simply because of a piece of cloth I wear on my head.”

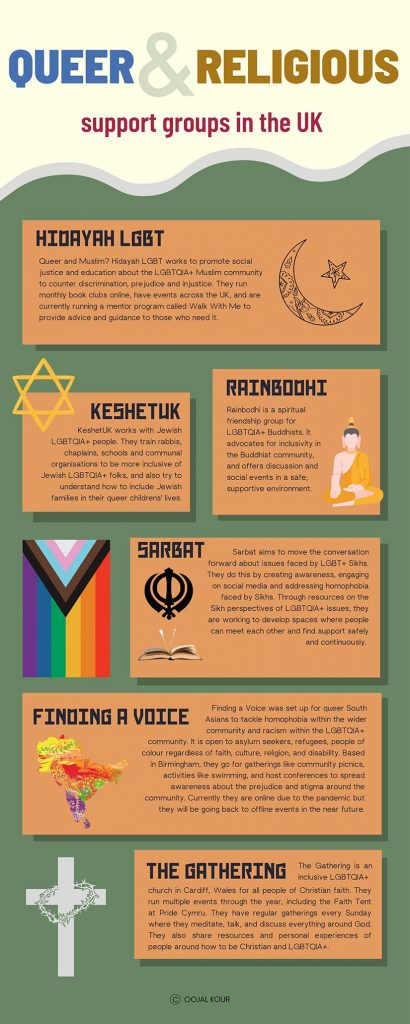

Luckily for her, she was able to find support through Hidayah. The Arabic term for ‘guidance’, the organisation was set up five years ago to be a space specifically for people who felt like they couldn’t be Muslim and queer at the same time. Today, it stands to provide welfare and a sense of community, while also emphasising activism against social injustice and discrimination on all grounds.

Deenah hopes that Hidayah can be a support system for many more Muslims in the UK who are hidden and queer. One of the ways she is trying to do that is by running a monthly book club online.

“You need to be around people like you and normalise certain things that might make you feel othered,” she says, adding that it is an incredibly important space for the participants who attend it even from the US and South Africa.

The book club focuses on privacy, cost-effectiveness, and providing a haven where people can have open discussions. Deenah says, “When we do our book clubs, most of us have our cameras off. There’s anonymity which you can guarantee. That doesn’t negate the experience for us because our chat will be very lively. We’re just giving people the space to communicate what they want, which can be helpful and liberating.”

The book club has received several positive reviews according to Deenah, who remembers a participant saying that it helped them come back to Islam. Another person felt that it was a safe space where they could be heard and accepted. “That is what Islam is about, standing up for the oppressed and running against injustice,” she says.

Working with Hidayah has made a difference in Deenah’s life as well, as she has been able to reconnect with her spirituality and learn how to embrace her faith more. Today, she has found a community where she belongs, with friends who are her chosen family. “It makes a huge difference because there is this feeling that I’m not alone,” she says.

For Khakan to find his chosen family, he had to realise that there was no point in waiting for someone else to help him do that – he had to do it himself. Thus, seven years ago, he founded Finding a Voice, an LGBTQIA+ charity to bring like-minded people together of South Asian heritage.

Many people weren’t comfortable in their own skin and were unwilling to speak out against any injustices, which inspired him to bridge that divide between multiple communities.

“It was about tackling homophobia and Islamophobia within the wider community, but also to look at how we could navigate prejudices within the LGBTQIA+ community as well,” he says. “It was to dispel the myths and the stereotypes, and to say that we come in different shapes and sizes and identify in different ways.”

For people to succeed in doing this, Khakan believes they need to be vocal and visible. “The only way you can do it is to fight it,” he says. “It’s about us being the kind of skin that we are, sharing the similar kind of cultures and traditions, and being able to overcome it.”

He asks queer Muslims to unite as an oppressed minority, and not succumb to the norms of the wider society. “We are just ordinary people wanting to lead our lives and be who we are. Whether you like it or not, we’re going to continue to be here.”