A bookshop is selling books that are banned in Hong Kong, and others are trying to remind the uniqueness of their cultural identity, why does it matter?

P loved visiting upstairs bookshops, mostly independent that couldn’t afford high rent when she was still in Hong Kong. It was the time before her family decided to leave the city for the UK because of the political suppression from China.

She is now running her own upstairs bookshop in the town of Loughborough, Leicestershire, where she says banned books in Hong Kong are available.

The desire to access these books shows in the sale of the bookshop. After P started to sell Revolution of Our Times: A Collection of Interviews, the transcript for a documentary about the 2019 protest that hasn’t been screened in Hong Kong, it has been listed as the best-sellers for months.

“It’s not sold in Hong Kong, but it’s well-received here,” says P. “Everyone wants to keep the record.”

The UK has opened its door to citizenship for eligible Hongkongers since early 2021, and figures show that 123,400 have applied for the British National Oversea (BNO) visa. The figure does not indicate how many people have actually arrived on British soil.

The surge of Hongkongers contributes to the success of P’s bookshop which she says the sale is much better than she expected.

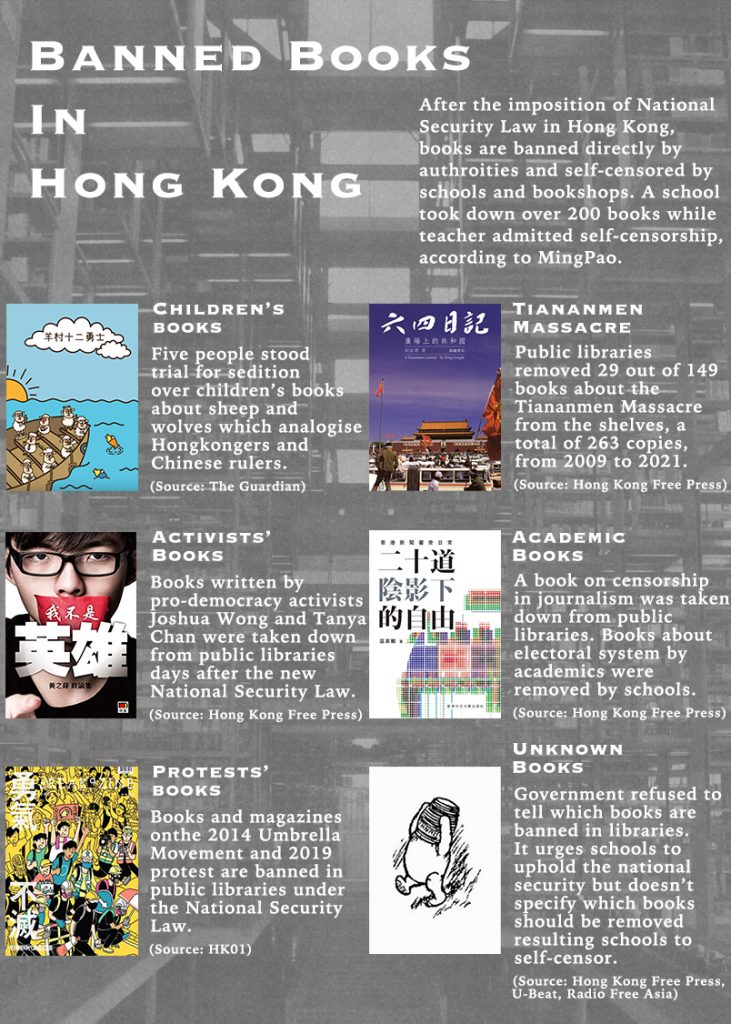

After the democracy movement in 2019 and 2020, the Hong Kong government took down books by democratic figures in the public libraries and refused to disclose which books were banned. Last month, three leading bookshop chains in Hong Kong declined to stock a new book by Chris Patten, Hong Kong’s last governor.

Being a book lover herself, P thinks reading books provides a chance for Hongkongers to explore their identity.

“How do you define yourself? Is it because we share the same history that’s why we are Hongkongers? Or is it because of the same belief? Or is it the place that defines you as a Hongkonger?” says P. “I think cultural and history books serve the purpose to answer these questions.”

The search for Hongkonger identity might happen way before the 2019 protest. P says she noticed more people visited independent bookshops after the 2014 Umbrella Movement, a 79-day occupation demanding democratic reform.

“A lot of people started to think about Hong Kong as a place, to think about being a Hongkonger,” says P.

As books are banned in Hong Kong, books make the preservation of identity possible in the UK. “No boundary separate Hongkongers from Hong Kong,” the bookshop’s website writes. “Connected through books and words, in common breath, we stand together for the revolution of our times.”

A flag with blue background and white words is hanging on the wall behind the counter. It reads “Hong Kong Independence”, a belief that P isn’t shy to admit. Reading, according to P, can prepare Hongkongers for this distant goal.

“If there’s a day you have your own country, what system should be used? What system suits Hongkongers? How to survive next to a big nation?” says P. “I think you need a lot of ideas way before it really happens.”

Some Hongkongers may be scared to speak out about Hong Kong because of potential retaliation against family and friends back home. For people who openly speak out like P, it’s a mission accompanies the identity of being a Hongkonger.

“I think we’re here in the UK already, if we’re scared to do everything, then there’s no big difference against staying in Hong Kong,” says P. “Now that I’m in the UK, I will try and see how much I can do.”

P’s bookshop mainly serves Hongkongers, but also attracts visits by Chinese on some occasions. P says: “Sometimes, I introduce books to them and it happens when they haven’t seen a single one of those books.”

Books are becoming more sensitive in Hong Kong. Last month saw the annual book fair banning publishers of books about the 2019 protest.

Early the month, an independent book fair, Hongkongers book fair, was axed by the venue owner. The venue owner told him the event had drawn too much attention on social media, according to the book fair organiser.

Given the tightening control on freedom in Hong Kong, P doesn’t feel like what she is doing will bring about concrete changes to the city, but she neither thinks it’s meaningless.

“I understand people in Hong Kong are really scared nobody is doing anything after two or three years,” P says. “For them, maybe it’s an encouragement. They will think people outside still remember them and want to help them.”

Calvin and his friends have been holding the Festival of Hong Kong, the anniversary of Hong Kong becoming a British colony, since 2014 to preserve the history of the city. But it was his first time organising the event outside Hong Kong citing threats to members.

“We didn’t want people not to remember things about the foundation day, so we decided to start over in the UK,” says Calvin, the organiser for the Festival of Hong Kong.

The turnout in the city of London was out of Calvin’s expectation with some 1,000 attended. “I’m happy to see so many Hongkongers want to get back their past, to get back their roots of Hong Kong spirit,” says Calvin.

Calvin says the 2019 protest has raised people’s awareness to understand the relationship between being a Hongkonger and the history of Hong Kong. Last year, when the annual event was still held in Hong Kong, about 2,000 showed up. Before the protest, according to Calvin, the event attracted twenty to thirty participants at most.

Despite its success, Calvin and his friends decided to relocate the event after the last year’s incident. “During the event, we saw someone was watching us,” says Calvin.

Hongkongers may not have a plan to go back and have their next generations grow up in the UK. Calvin thinks it’s important to have a sense of identity being a Hongkonger.

Hongkongers are not just people who live in Hong Kong, says Calvin. It’s about the characteristics of the people.

When you have a strong sense of identity, according to Calvin, you can’t get rid of it no matter which parts of the world you are in.

Calvin organised a series of talks on Hong Kong’s history. He says the content is designed from the perspective of Hongkongers, neither a Eurocentric nor a Sinocentric approach. He and other members also held a two-day event at Bingsutt, a Hong Kong-style café.

It is a new challenge for Calvin. “We hadn’t thought about having two events in a year. In the past, we’re an organisation only for Foundation Day,” says Calvin.

The promotion of Hong Kong culture has been important to Calvin as he studied for a master’s degree in it and published a book.

His interest came from encounters with foreigners. He says they had difficulty understanding that Hong Kong culture was different from Chinese. “I felt like if I had to let people truly understand that, I had to spend more effort to study how can I explain to them,” says Calvin.

He then wanted other Hongkongers to understand the uniqueness of their culture. He says: “I do so much study and other stuff because I want to let more Hongkongers to know their past and roots and to use the simple way to explain to others people what Hong Kong culture is, and why we’re not Chinese.”

Calvin felt he was a Hongkonger but not a Chinese when he was a teen. It echoes the feeling of lots of Hongkongers.

An average of 39.1% identified themselves as Hongkongers whereas only 17.6% said they were Chinese, according to findings of a Hong Kong independent study, released in June. Only 2.2% of people under 30 would have sensed themselves as Chinese.

Other organisations also attempt to promote Hong Kong culture. Hong Kong Film Festival UK, for example, had its inaugural event in March across four British cities.

A cinema had its website crashed due to the unexpected turnout to secure a ticket for Revolution of Our Times, the documentary about the 2019 protest which had its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival.

“We want to find a way to narrate Hong Kong stories in turbulent times through films,” Wong Ching a co-curator of the festival told Variety. “It is about maintaining the Hong Kong cultural identity.”

Calvin thinks his organisation has tried to make history interesting. “History itself is hard to digest, it’s boring to a lot of people including myself,” says Calvin.

They are still trying to make their message clear and influential. He says: “Of course, we’re still not doing well right now, after all our posts don’t have many likes. Neither the design nor content is catchy enough. We’re gradually exploring our direction.”

In September 2022, London will host the first Hong Kong Bookfair in the UK.

Next January, the Museum of Hong Kong will organise the 10th Festival of Hong Kong for three days.

(updated: Museum of Hong Kong said that they celebrated the Festival of Hong Kong because it was the anniversary that the territory was called Hong Kong.)