Hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers will emigrate to the UK in the post-protest era, why do YouTubers think it’s important to play a role to assist them?

“If you are a short lady like me, remember to bring more trousers,” says Moon Ma, or Mother Moon, in a YouTube video reminding her audience who considers leaving Hong Kong for the UK. She says: “It’s hard to buy trousers that suit me because the people are taller and thicker in the UK.”

The police raid of the headquarter of Apple Daily, a pro-democracy news outlet and Moon Ma’s employer, made her feel the authorities’ attack on freedom and later take up Westminster’s offer to start a new life in a free society.

“I was disappointed and hopeless about the prospect of Hong Kong, and I didn’t want my daughter to grow up in that environment,” says Moon Ma, a YouTuber who introduces things in the UK ranging from renting houses to holiday destinations, food, and driving exams.

Moon Ma, her husband, and her daughter departed in March 2021 after tireless effort in researching information about her new host country. “I’ve been through it,” says Moon Ma. “I wanted to use my experience to help the people who may come to the UK.”

Hongkongers living under the Chinese Communist Party’s rule have seen their dream of a free and democratic society flee away. In June 2020, China bypassed Hong Kong’s legislative process to impose a National Security Law which claims to criminalise any act of subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces while critics say it is another tool for authority to suppress dissent.

Powerless to bring changes to the city, many Hongkongers have started to think about leaving the city – a phenomenon once happened in the nineties before China took control of Hong Kong from the British.

The longing for a relatively free society has come to a reality for some after the launch of the British National Oversea (BNO) visa in 2021. YouTubers have been among the wave of immigration and they turn their channel as a platform to lessen the worries of Hongkongers who consider leaving Hong Kong.

“You can only have freedom of speech, press and assembly only if you leave Hong Kong,” says Moon Ma who has attended several rallies to raise awareness about Hong Kong in the UK.

There are 123,400 applications for the BNO visa up to the end of March, according to Home Office. At the same time, the Hong Kong government statistics show that the city just experienced the largest mid-year population drop on record, resulting in over 113,000 residents leaving.

Hongkongers look for help on the Internet including through articles, Facebook groups, and YouTube videos.

Hong Kong YouTubers have shared about chores in the UK since the beginning of the immigration wave which they wouldn’t have imagined. Citing political reasons, the founder of Arm Channel TV, a Hong Kong-based YouTube channel which has 300,000 subscribers, announced to emigrate and start another channel to tell Hongkongers’ stories in the UK last August.

“I wouldn’t have thought of using my channel to talk about immigration,” says Moon Ma. Her channel was originally a parenting channel and it has transformed thanks to the government’s crackdown which led to her decision to leave.

Although coming to the UK for a liveable society, some YouTubers also generously share their undesirable experiences, including public safety issues, language barriers, and uncertain weather.

Hong Kong Walker, another YouTuber, says in a video that he was once called a virus in the street. Some experiences, he says, make him feel like he is a second-class citizen.

Cultural shock is a shared difficulty among many Hong Kong immigrants, but living in the UK guarantees them chances to speak out and raise awareness of their home country.

Rallies are seen every month in the UK to raise awareness of the Chinese grip on Hongkongers’ freedom. 12 June, for example, marks the start of the 2019 protest and police brutality against protesters, and Moon Ma attended a rally that day.

“I think protest is already impossible in Hong Kong because of the imposition of National Security Law. If you continue to chant or protest, authorities can use the law to arrest or prosecute you,” says Moon Ma.

For decades, Hong Kong had been the only place in China to hold an annual candlelight vigil to commemorate the hundreds of deaths in the Tiananmen Square Massacre. In 2020, Hong Kong authorities for the first time banned the vigil.

Last year, the vigil organisation disbanded after many of its members were arrested for violating the National Security Law.

Since 2003, Hongkongers had held a rally every 1 July, the anniversary of Britain handing control of Hong Kong to China.

In 2020, thousands of Hongkongers defied a police ban and gathered to protest. It was the last July 1 protest seen in the city.

Besides grassroots efforts on YouTube, dozens of organisations have also been founded to help newcomers to adapt British life. Umbrella Formation is on the list.

The organisation has held workshops for children, visits to a brewery, and lunch gatherings. Terry Leung, the founder of the organisation, says the wave of immigration itself poses pressure on the Hong Kong authorities.

“When people leave, they also bring their money, that certainly puts pressure on the government,” says Terry.

Moon Ma agrees the wave of immigration is a loss to Hong Kong as the city faces capital outflow and brain drain.

Carrie Lam, the then leader of Hong Kong, responding to the surge in emigration, said that the administration would recruit talents from mainland China and overseas.

People who left Hong Kong would eventually realise how good the city was, she said.

Although Terry agrees that leaving the city may mean having more freedom and showing the government that people are losing trust in her, he also says that people should think twice about staying or leaving.

“I don’t preach about everyone to come to the UK,” says Terry. “You have to think about whether moving to the UK is right for you or not. If it doesn’t work for you, then that’s fine not to come.’

Some Hongkongers believe staying in their home country serves the best to continue the democracy movement. Jimmy Lai, the founder of Apple Daily where Moon Ma worked, said he would not leave Hong Kong after the imposition of the National Security Law.

Lai said he wasn’t scared of imprisonment. Now, Apple Daily is closed and the 74-year-old is in jail and still facing other criminal cases.

Yau Wai Ching, an ex-lawmaker who was disqualified by the court after Beijing’s intervention, urges Hongkongers to stay in the city in a video in response to the trend of immigration.

“This trauma may take several years, or even several generations to heal,” she says. “We are the doctors of this place.”

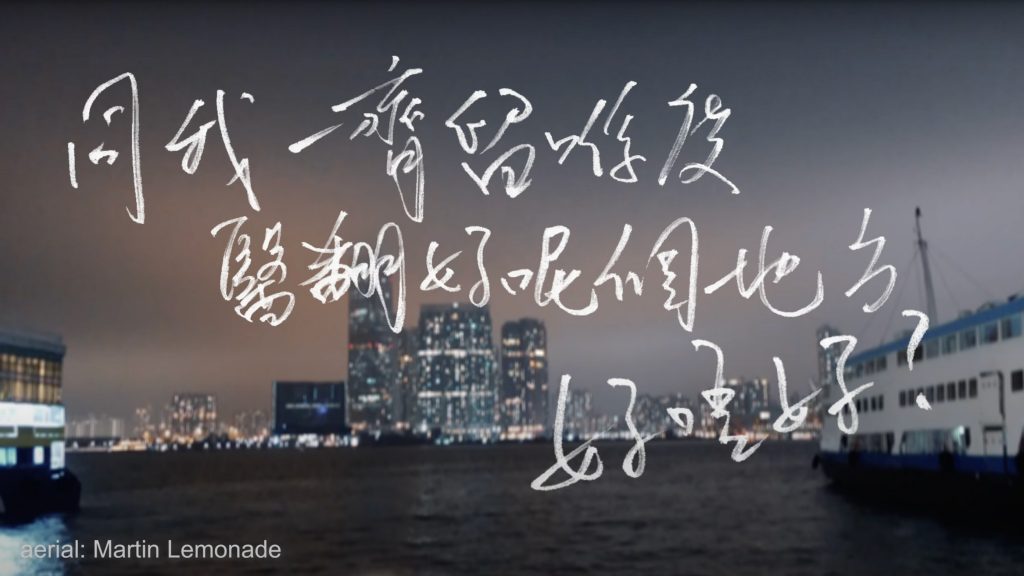

At the end of the video, she asks: “Stay here and heal this place with me, okay?” signalling that if more people are leaving Hong Kong, the prospect of the city will just get worse.

Some Hongkongers, however, somehow don’t feel they have a choice. Chung Kim-wah, a social scientist who is a member of a public survey institution, left Hong Kong for the UK in April saying he had no choice but to be a deserter.

Others, who may not be a public figures, share the feeling of urgency to leave the city due to the vagueness of the red line that will put them be the target of the regime.

Last November, three people were arrested for reposting an online appeal for blank ballots in the legislative council election, in which no opposition took part as many pro-democracy politicians were arrested, imprisoned, and went into exile.

Terry recognises that some people can’t afford to leave Hong Kong and live in the UK. Even still, he believes they will try their best to do whatever they can within the red line to contribute to the pro-democracy movement.

On the other hand, Hongkongers in the UK, should, according to Terry, try hard to assimilate into British society and also help others to adapt to the new environment.

For more than a year, Moon Ma has been a pseudo-immigration consultant, and she is still facing difficulties ranging from living pace, food, language, weather and income in her new home.

The family income is much less than that back in Hong Kong, says Moon Ma. She and her husband both went to work before leaving the city.

Moon Ma is now a housewife to take care of her daughter and handle all the chores. The family hired a domestic worker when they were in Hong Kong.

From things to bring to the UK, reminders when renting a flat, to recommended apps for downland and farms to visit, Moon Ma pledges to update her channel every week to the potential Hong Kong leavers.

Activism like rallies in the UK, Moon Ma says, serves also people in Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong hasn’t shut the Internet yet,” she says. “People can still attain the information online.”