Next year, face surveillance is believed to become so unconstrained that it can detect people with masks. How do a couple of artists use their talents to fight back?

Unlike most artists who draw on canvas or paper, Anna Hart was looking in the mirror, painting her face with a few black strokes, one of which boldly crossed through the bridge of her nose, creating an outlandish and asymmetric pattern.

She was preparing for an upcoming Zoom meeting, in which all the participants would be drawing their faces, learning how to use this unique form of art as a way to deceive facial recognition cameras.

“Let’s dazzle up,” Anna said after a dozen faces turned up on the laptop’s screen. With upbeat background music, attendees started to decorate their features with a variety of material they have on hand. Some taped flamboyant pieces of paper all over their foreheads; the others painted geometric shapes on their cheeks with lipsticks and eyeliners.

“I don’t call it a protest. It’s just sort of a form of performance,” said Anna, co-founder of the Dazzle Club, a collaboration of four artists that question the use of surveillance technology in public. “But it’s great if it did draw awareness,” she added.

Founded in August 2019, the artist-led group used to host monthly silent walks in London prior to the pandemic lockdown in response to the trials of facial recognition surveillance carried out by the police and private companies. It then soon drew significant attention due to the eye-catching, vivid make-up they wore when marching down the streets.

The face-drawing technique, also known as CV Dazzle (Computer Visions), was first created by researcher Adam Harvey, who developed it into an artistic and functional type of camouflage in an attempt to hide his face from detection.

“Since facial recognition relies on identifying relationships of key facial features like symmetry and the colour of the face”, said Georgina Rowlands, one of the co-founders of the club, “the geometrics patterns can work to combat that detection in similar ways, what Adam called the anti-face.”

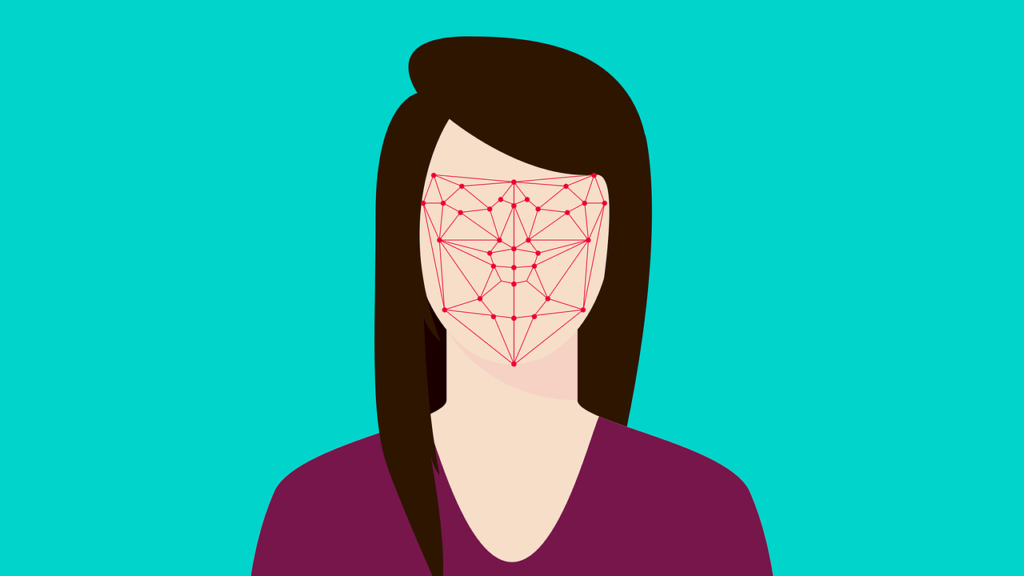

Rather than an ordinary photograph, facial recognition software will calculate distances between a person’s key face features and turn them into a biometric map composed of thousands of dots and lines.

When used for surveillance, it is then well combined with Big Data and computer algorithms; one of the best examples is automated facial recognition (AFR), a digitised surveillance system working with live cameras invented to identify individuals and filtered out the targeted.

Image: The Dazzle Club.

“There will be a database somewhere storing a link between the person’s information (e.g. name) and a biometric fingerprint which represents their face,” said Oli Bartlett, the product manager of DataSparQ, British AI firm, adding that the detection would compare the face it sees with others on that database to check if there is a match among tons of different biometric maps.

Ideally, CV Dazzle can work effectively to paralyse face detection, but as the algorithm is an intelligently self-improving system that would only get smarter after more practices, the modern camouflage cannot always guarantee a successful trick in front of the cameras.

Instead, it has done a better job to demonstrate an act of defiance in an innovative way. “We are interested not just in building the awareness of how our images and data has been gathered,” said Anna, “but also in building new expression and sociable resistance with collective and creative expression.”

Yet, as a country reported to have over six million cameras, more than any other nation except China, Britain is actually known for its relatively high acceptance for developing surveillance technology among other Western democracies.

Few in the UK share the same concern as the artists do; citizens are said to sit comfortably with myriad monitoring cameras, due to either the belief of promises for security enhancement or the obliviousness to copious CCTV and how surveillance has been developed around them.

As Anna described, after Dazzle walks, people’s most common feedback was: “Wow! I didn’t realise there were so many cameras everywhere.” She found this reaction “interesting” because none of the club members had pointed out any cameras during marching. “So, it’s a way of paying close attention to what’s going on in our cities,” she said.

“It’s not like being watched is a new thing. Who is visible? Who is giving permission to be seen and not to be seen?” Anna said, emphasising that what prompted her to take action was not the scale of camera installation, but the rapidly increasing surveillance in public.

A 2019 survey showed that in fact, up to 63% of Britons supported the police using facial recognition for criminal investigation. But the figure fell dramatically in terms of day-to-day policing. This result, researchers noted, indicated that people didn’t know much about the new technology but hoped the police can introduce it under proper legislation

Back in the 1960s, CCTV cameras already covered certain areas of London and have proliferated since then. However, it’s by the late 1990s that biometric identification started to spring up due to heightened terrorism in the West. Nowadays, the entire landscape has changed over the past decade as surveillance combined with facial recognition has become more prevalent than ever.

A report suggested that the use of biometric technology had increased by almost 30% from 2005 to 2010, and the worth of the biometric system market was estimated to stand at $65.3 billion by 2024, which would nearly double the figure in 2019.

Due to its lucrative potential, Western countries are now competing to develop facial recognition, ambitious to lead the race to dominate the global AI market. And Britain is no doubt one of the states that embrace this tendency.

In the UK, facial recognition cameras have already been deployed in many public spaces with or without people’s knowledge, and private businesses are keen to advance the technology and cooperate with governing bodies.

A case in point is Facewatch, British leading facial recognition company. Its products have been widely used in bars and grocery stores in England to prevent and reduce cases of shoplifting. And Argent, the UK tech giant, has installed the AFR system at King’s Cross Estate to help the police detect crime.

Also, privacy campaign groups such as Liberty and Big Brother Watch noted that Live Facial Recognition (LFR), the real-time facial identification technology similar to AFR, had been rolled out by the Metropolitan Police with no parliamentary debate since 2015.

In London, ten trials of LFR were staggered throughout last year with camera-installed vans parking at some of the most densely populated areas. A news video from the BBC also showed that a citizen who covered his face when passing through the camera ended up paying a £90 fine for obstruction and having his photo taken forcefully.

When Anna first joined a demonstration launched by Liberty, she also found the operation rather disturbing. “There were twenty uniformed police. We know there’s a lot of plainclothes police around the operation too,” she said. “People crossing the road cannot come through because it’s semi blocked, and they would be stopped by the police.”

(The material used in this video is attributed in YouTube description box)

Despite campaigners’ opposition, in January this year, the Met further started using LFR with CCTV to identify suspects on the streets rather than simply trialling it by facial recognition vans. The operation once again led to a huge backlash from civil rights organisations, although the police said they had informed local communities in advance.

The Met insisted that it was in the public interest to integrate LFR technology as a policing tool to firstly, reduce the expenditure of police deployment and secondly, to enhance the efficiency of catching wanted-offenders and “taking a dangerous criminal off the streets”. But as for the latter, there is little evidence to prove it is true and even the police said in their internal report that its measure “is harder to quantify”.

Besides, when it comes to preventing crime and capturing criminals, face recognition can also be quite desirable to shop owners. Not to mention identifying shoplifters and offenders on a watchlist, many businesses are likely to boost their revenue from a more efficient, technology-driven service.

For example, in 2019, DataSparQ released an unprecedented product called AI Bar, using facial recognition to identify customers. With no need to present ID to be served, it drastically reduced the serving times and long queues. “It’s a frictionless ID for the customer,” said Oli Bartlett, the product manager of the company.

But what’s worth noticing is that although the revolution was reported to enable pubs to serve around 1,600 additional pints each year, it turned out that DataSparQ had to suspend the product because of restrictions in accordance with the EU’s data protection and privacy law: General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

“We need to get explicit consent to use biometric data to identify a person – we need to identify the person so we can track them through the queue. Getting explicit consent on entering a bar isn’t really workable,” Mr Bartlett said.

In this case, GDPR seemed strict enough to successfully protect people’s biometric information from being exposed as it made the operator liable for obtaining a formal affirmative response before conducting the system.

And more reassuringly, Brexit didn’t bring much difference to the overall rules, except for a few big changes, one of which was that the leading supervisor and regulator of the law is no longer an advisory panel of the EU but Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the British data protection regulator.

However, the Met wrote in a report, “As an emerging technology, LFR is not subject to dedicated legislation.” In other words. no specific law is now limiting the use of face detection and holding state authorities to account.

“A lot of surveillance adapting and changing because of the pandemic,”

Emily Roderick, co-founder of the Dazzle Club

The LFR trials police have conducted regardless of controversy were declared to be appropriate because according to the ICO, the data protection law was “flexible to ensure that biometric data can be processed in compliance with the essential legal obligations and safeguards”. It is clear that the use of facial recognition is growing at break-neck speed in the UK with few obstacles.

At the same time, surveillance technology seems to have gained more public acceptance following the COVID-19 pandemic as it has become an efficient method to weather the widespread infection after being applied to the healthcare system and virus-tracking applications.

“A lot of surveillance adapting and changing because of the pandemic,” said Emily Roderick, co-founder of the Dazzle Club, which stayed active by hosting virtual Dazzle Walk during the lockdown. “It’s important to continue those discussions and it’s very topical now to keep those thoughts out there for people.”

Additionally, although the pandemic has rendered wearing masks a common thing among people, it is estimated that by 2021 any face coverings can no longer help one slip through the dense monitoring network.

Because a state-funded research project led by the University of Surrey called FACER2VM is underway, aiming to bring biometric industries to a new level where the detection can still identify individuals with their appearances covered.

The project is also being conducted with Jiangnan University in China, a country that is believed to have the most advanced surveillance system and has shown the world how powerful and abusive the technology can be by putting ethnic minorities under strict supervision.

A British researcher wrote in the report, “Unconstrained face biometrics capability will significantly contribute to the government’s security agenda in the framework of smart cities and national security.” Apparently, the UK is heading towards a surveillance state.

Though compared to a communist country, democratic regimes seem to have more robust laws to protect personal data from being misused, academics in the UK still warned that without further legislation, developing face biometrics can be problematic, especially when merely a minority of citizens are aware of the underlying crises.

It is not as though democracy would suddenly collapse, as a senior correspondent – Kai Strittmatter noted in his book about Chinese surveillance system, the main concern was the government’s reckless attitude towards new technologies.

After all, technology can be fairly neutral, or some say it is like a double-edged sword, composed of benefits and drawbacks, and the outcome highly depends on who owns and how one uses it. But when it comes to automated facial recognition, the design is intended to be intrusive by monitoring people’s behaviour and assuming them to be suspicious.

That is to say, when westerners are pointing their fingers at the Chinese government for its abusive surveillance system, how can people make sure the technology with great potential to be oppressive will not be misused in the UK, either deliberately or accidentally?

Either rushing into a nationwide biometrics CCTV system or slowing down the development until rigid legislations are put in place, Britain seems to not consider a thorough ban on facial recognition as some states in the US do. If it is inevitable for the UK to become a data-driven surveillance society, the question is, are Britons ready to enter?

The best response to the rhetoric is probably to stay educated and wary of the controversy between the surveillance system and civil rights, as the founders of the Dazzle Club, who cast doubt on the use of LFR, empowering individuals to realise the negative impacts through actions and discussions.

“We’re really interested in doing things together, paying attention to things like this,” Anna said. “The really great thing about the collaboration is that it came out of a conversation between the four of us, as women, as artists, as human beings.”