Times of upheaval have been the source of inspiration for some of the world’s greatest pieces of art. As we emerge into a post-pandemic world, how are UK artists capturing one of the most unforgettable periods of the 21st century?

Tom Badley

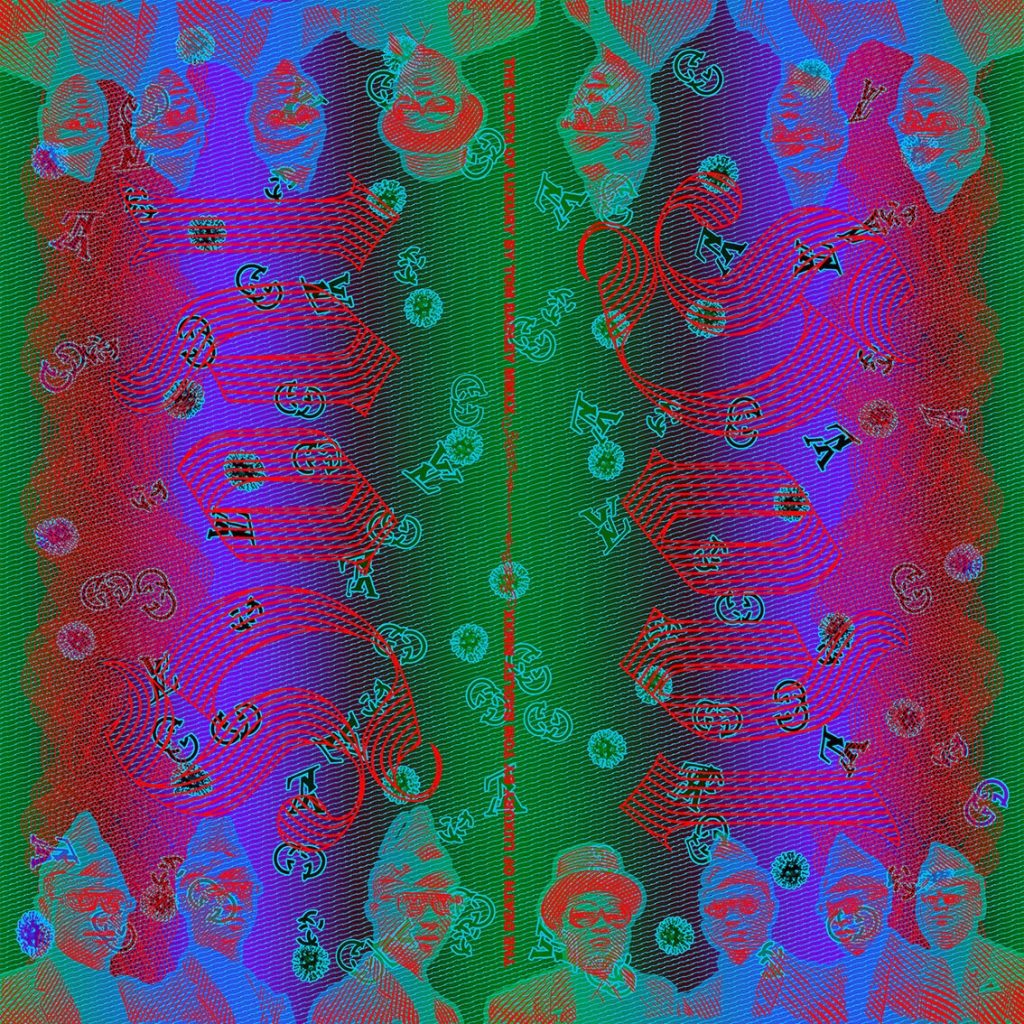

‘PUMP IT’ (2020) by Tom Badley, courtesy of Tom Badley

Memes, coronavirus, the stock market crash and the rise of cryptocurrency are what have defined the year 2020 for artist Tom Badley. Despite coming from a fine art background, Badley has become of the few ‘cryptoartists’ in the world today, using banknote and cryptocurrency-making techniques to create money-inspired art.

Inspired by 2020’s major themes and events, Badley created ‘The Death of Luxury’, a series of nine NFTs which are printed onto silk scarves.

“The whole artwork is about how traditional luxury stores, they felt the brunt of the pandemic because obviously, no one was going into the stores,” he said. “Traditionally luxury goods companies like Versace and people like this, they are terrible at maintaining an online presence. So, they were forced to be online.”

‘HODL’ (2020) courtesy of Tom Badley

‘Dow Crash’ (2020) courtesy of Tom Badley

Badley’s use of NFT design is also significant too. NFT’s, also known as ‘non-fungible tokens’ are digital assets which represent objects such as videos and art. Unlike other cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoins, NFT’s are unable to be exchanged equally which has created digital scarcity. NFT’s have seen a recent boom in the artworld as a way to create, sell and buy artwork.

“This is the year in which Christie’s and Sotheby’s have held really high-profile auctions of digital assets,” said Badley. “So, it was quite a prophetic artwork in that sense, because luxury did die and then it was forced to reinvent itself and become digital the next year.”

Iconic references to the pandemic are dotted throughout the nine works. The piece ‘PUMP IT’ features a cluster of coronavirus particles floating around the artwork. Badley also plays with references to popular and digital culture incorporating viral symbols such as ‘Coffin Dance’ meme.

‘With the pandemic, obviously everyone was stuck and home,” said Badley. “Everyone is hyper-aware of the memes that are on their screen. A lot of those memes found their way into my artwork”

“So pretty much when the market was crashing, and the pandemic was just coming in and governments were just responding to it, there was a meme going around of these coffin dancers. So that just captured the moment perfectly, because it was used whenever anyone failed and the whole world was failing.”

Melinda Matyas

Melinda Matyas’ art series ‘Heroes behind closed doors’ captures the hidden lives of everyday people, sheltering inside as the coronavirus spread. The London-based artist became intrigued by how differently people coped in times of crisis and how this often led to conflict.

“The rage, the hopelessness, the lack of self-composure showed up everywhere, in everyone,” she said. “People became more ‘visible’, showing their real nature in the face of adversity, and that is what really fascinated me throughout the pandemic, and this series was the outcome of that.”

As households were forced together like never before and as peoples’ worlds became restricted to the four walls of their home, Matyas observed peoples’ growing inability to communicate with one another. This became the inspiration behind the painting ‘Silent Distance’.

‘Breakfast Forever’ (2020), courtesy of Melinda Matyas

‘Rising Sun’ (2020), courtesy of Melinda Matyas

“Silent distance represents three people, maybe friends, maybe a family, sitting at a table having dinner, but having nothing to say to each other, which shows what happens when they are forced to be in each other’s presence for too long,” said Matyas.

Simon Hopkinson

Simon Hopkinson has always been fascinated by some of the UK’s forgotten places, locations where most wouldn’t look twice.

Unafraid of dark and emotive material, the pandemic provided the Devon-based painter with new and compelling material. With a new boost of creative purpose, Hopkinson began painting the deserted scenes outside his home and documenting the UK’s strange new reality.

“The first one I did was started in February 2020 and finished before the first lockdown, and was intended as darkly mischievous,” said Hopkinson. “While many artists tried generating some optimism, for me the new landscape seemed to validate and encourage my taste for dystopian imagery.”

Hopkinson’s piece ‘Vax Utopia’ depicts his view whilst waiting for the bus home after visiting his local vaccination centre, where an ‘eerie post-normal feeling seemed to haunt the summer countryside,’ he said.

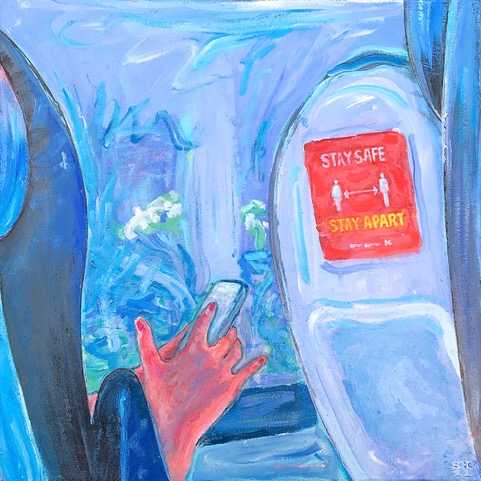

The painting ‘Stay Safe, Stay Apart’ documents Hopkinson’s first tentative return to public transport last April. He noticed a ‘Stay Safe, Stay Apart’ sign, just one of many other reminders of Covid plastered across public spaces. “Together with the hand and phone seemed like good material” he said. “The sign seemed to have wider symbolic significance, bringing to mind other reasons apart from infection risk why people might want to avoid each other.”

Like many, one of Hopkinson’s main reasons for leaving the house was to exercise, taking walks at night around the streets of Exeter. He began noticing the small risks people took to carry out what once were normal day-to-day tasks. A man sat alone in a takeaway piqued Hopkinson’s interest, this resulting in the painting ‘Breath Threat’.

“I’d done quite a few paintings of people alone in public spaces before the pandemic which aimed to reflect social isolation or sometimes, in more confined settings, the sense also of a trapped self,” Hopkinson said.

“The one in the painting lends something disturbing, I think, to scene which might be called slightly Hopperish, both by adding to a slight sense of claustrophobia and reminding that the air you breath these days is potentially lethal.”

Mary Rouncefield

Inspiration was hard to find when the pandemic hit for Bristol-based artist, Mary Rouncefield. It wasn’t until she took some time to admire some of Picasso’s famous masterpieces, that she felt a spark of inspiration return.

The late master’s depictions of anxiety and human suffering seemed to reflect what was happening in the UK, she said. Determined to get over this creative lull, she searched her house for left-over canvases and began experimenting with Picasso’s style, channelling her thoughts and fears about the pandemic.

Rouncefield’s ‘A Hidden Enemy’ takes inspiration from Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, an iconic anti-war scene that portrays the suffering of the Spanish Civil War. The pandemic seemed to be a battle too, she said, with healthcare workers risking it all on the frontline to treat thousands of people falling ill and dying from coronavirus in the UK.

‘Woman In A Mask’ (2020), courtesy of Mary Rouncefield

“People were talking about the fight against the virus and war, and I remembered Picasso’s piece Guernica,” she said. “He used that painting to show a massacre of really quite ordinary, innocent people in a village in Spain. I felt that quite ordinary, innocent people were dying here in a different way.”

Rouncefield also strived to capture the widespread anxiety felt by the UK population, drawing inspiration from Picasso’s distorted facial expressions. She began to incorporate an item into her paintings that has become symbolic of the Covid-19 pandemic, the facemask. An item that has come to be the source of recent political and societal divides. Rouncefield was most interested in how facemasks changed how people saw each other, and although they obscured peoples’ faces, fear can still be seen in their eyes.

Darcey Murphey

The pandemic left art student, Darcey Murphey, feeling like she was stuck in time. Like many other students, she moved back home during lockdown, but she was stranded without any of her normal art supplies.

However, this forced the art student to begin experimenting with new materials. Using one of the only resources she had, soft pastels, the 21-year-old artist began to make art which reflected her mental state and how her world had seemed to have come to a stand-still.

“I think I was able to reflect my feelings of exhaustion but also calmness with Covid, and how I felt as though I was just floating through it,” she said. “Looking back, I think my work was a way for me to escape and make the most of the pretty bad situation we were all in.”

This sense of suspension in time is captured in Murphey’s work ‘Jellyfish’, depicting a human form floating in the air supported by a luminescent cluster of marine creatures.

Murphey also decided to use her work as a political statement, to vent her frustrations at the UK government’s handling of the pandemic. The piece ‘Day 1 Day 2 Day 3’ depicts buried human heads emerging out of some soil as a figure buries them like plants, a scene reflecting the UK’s rising death toll. Murphey also refers to a looming feeling of unease during lockdown, an awareness that whilst people tried to continue their day-to-day tasks, people were dying across the UK.

“With this piece I was attempting to reflect how everyday life had just become a bit weird even when doing normal things such as gardening,” she said. “Something just didn’t feel right!”