“Where are you from?” is not an easy question for 21-year-old Christopher Kuo who born in Germany.

(Images from Christopher)

I have to think about it if I am a Chinese or a German because I am not sure who I am, but I act like a German,” says Christopher Kuo.

“‘You don’t look like us, your eyes are Schlitz Augé (offensive in Germany language,’ which means chick eyes in English). Are you Asian or Chinese? ” This confusion about identity stems from a question that Christopher has often encountered at some point since he was a child.”

Christopher Kuo was born in Hildesheim, Germany, which is a small city so there were very few Asians. He remembers once when he said paying by credit card in German in a shop.

“The shop assistant looked at me so surprised and said ‘you could say it in German, I thought you were going to say it in Chinese.’ I could understand that he maybe didn’t mean any harm, but it still made me confused about who I am when others asked more questions like that. “

Christopher is far from alone in his experiences. Ferat Ali Kocak, an anti-racism activist in Berlin said: “It became clear to us that for various reasons, anti-Asian racism, even if it’s not always visible, is strongly anchored in German society.”

This prejudice has long existed not only in Germany, but also in Europe. Based on actual and imagined to Asia, Europeans have constructed and disseminated images of Asians as ‘different’, ‘exotic’ and ‘dangerous’ since the 13th century to this day.

The history of Germany reflects the fact that from the beginning of the Nazi regime, Asians living in Germany were deported or expelled to concentration and labour camps. The effects of this anti-Asian racism continued to be prevalent even in the decade after German reunification.

Throughout history, it is not only Asians who have experienced such hatred. Prejudice against foreign populations was exacerbated in 2015 following the influx of some three million refugees into Europe.

So, when early Chancellor Angela Merkel adopted an open-door policy towards refugees and admitted one million, this led to a number of shootings against Muslims as well as refugees, and many parliamentary candidates with a migrant background also received death threats. This racism, which is deeply rooted in German society, has been fuelled by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency’s 2020 survey, racial discrimination in Germany has increased significantly. There were 2,101 complaints, compared to 1,176 in 2019. Verbal and physical attacks against Asians accounted for the majority of them.

Asians living in Germany, Germans with a history of Asian immigration, and people who identify as Asian have expressed a rise in anti-Asian hatred.

Christopher also met more new friends at university. Just as he was beginning to look forward to university life. With the outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan, China, Christopher was in more serious crisis.

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Corona-Pandemie (which means Corona-Pandemic in English) has become the German buzzword of the year for 2020. During the Corona-Pandemie period, Asians living in Germany, Germans with a history of Asian immigration and people who identify as Asian report an increase in anti-Asian hatred.

These findings stem from a survey of 4,500 participants’ attitudes in Germany by the German Centre for Migration and Integration Research (DeZIM) and a survey of people with a history of Asian immigration in Germany by the Humboldt and Free Universities.

When I get on the train everyone quickly distances themselves from me. No one dared to sit next to me, recalls Christopher.

And in the beginning, when my parents wore masks on the train, some people would walk away and laugh. But I think it was better than when they said, “Go back to your country.”

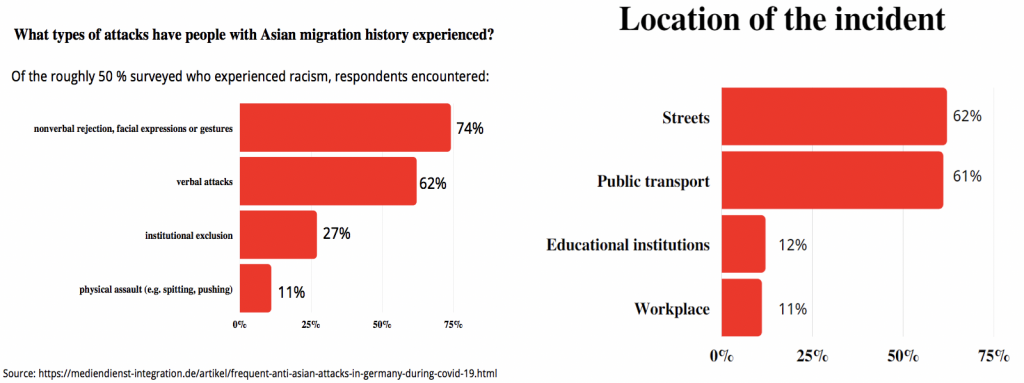

The report also confirms that Christophe’s and his parents’ experience is not an exception. During Covid-19, 74% were subjected to non-verbal discrimination in the form of gestures or facial expressions. 62% received verbal abuse and 11% were subjected to physical abuse, such as being sprayed with disinfectant. Even 27% reported being excluded from institutions such as hospitals or doctors’ surgeries.

These incidents occurred most often in the streets (62%), on public transport (61%), but also in educational institutions (12%) and in the workplace (11%).

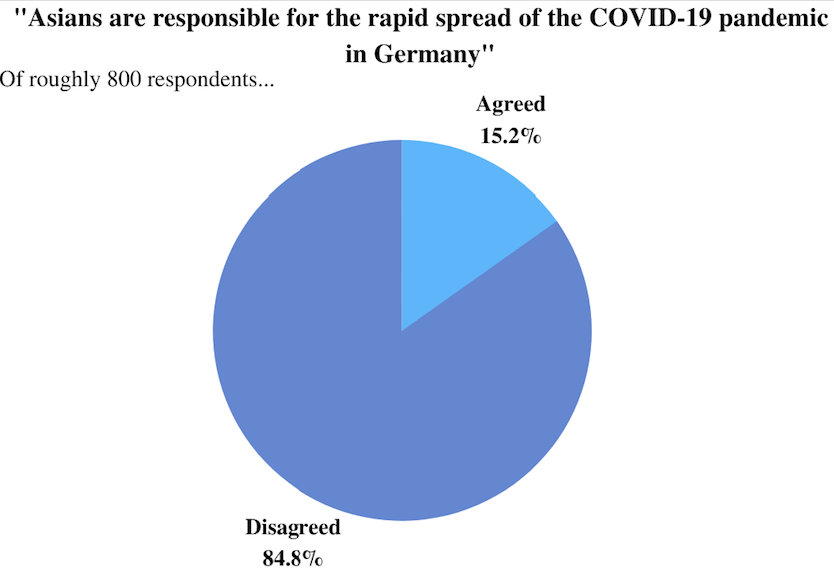

Furthermore, in a population survey, more than 15% of the 800 Germans interviewed believed that “Asians are responsible for the rapid spread of COVID-19”. Of the 4,100 respondents who identified themselves as white, 10.8% said they “would feel uncomfortable having Asians as family members.

Christopher believes that this anti-Asian sentiment in Germany also stems from some differences in medical perceptions.

“When the epidemic first started, my parents were already wearing masks before the government made it compulsory to wear them in public places. The Chinese felt that the masks would protect them from infection. “

Christoper says that Germans do not understand this behavior. It is a common belief in Western culture that a healthy person does not need to wear a mask. “People think that wearing a mask is because you are sick. Even then the news said we don’t need the mask. “

Even now that the government has started requiring masks to be worn in public, Christopher says you can still see people either wearing masks with their noses showing or pulling up their T-shirts to cover their mouths before entering the supermarket.

But for my parents and my grandmother in China, it couldn’t happen,” Christopher says with a smile.

Christopher Kuo is already a third-generation Chinese who grew up in Germany, but this does not seem to have allayed the fears of Christopher’s parents that their son’s identity would not really be recognized.

His mother still vividly remembers as a child when the first time Christopher was teased and rejected by his classmates because of his Chinese appearance.

“The teacher called me into school and when I heard what had happened, I was really upset. I didn’t want him to have to deal with that at such a young age because we chose to live in Germany.”

For Christopher’s parents, a different appearance from the Germans did not serve any purpose other than to create difficulties for their son’s future.

“Even though he has a Chinese face. But he doesn’t speak Chinese very well, and he doesn’t have any friends in China. So, it is unlikely that he will return to China in the future. And since he was born here, Germany is his homeland.”

A 2008 study involving Debbie Ma, a professor of psychology at California State University, Northridge, reinforced the habit of judging people’s race and identity by their appearance.

By having American college participants of different ethnic backgrounds and ages were more likely to implicitly think Kate Winslet, the English actress, as “American”, than Lucy Liu, the New York-born star of Chinese heritage.

“Because of that,” Debbie Ma says, “it’s very easy to quickly label and assign stereotypes and associations with those categories” – that an East Asian person is foreign, even if they are not, for example.

This is why many Asian immigrants, including native-born people like Christopher, are still trapped in this identity dilemma. Their different appearance from Westerners makes them a “minority group”.

Frank W, the author of the book ‘Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White’, describe this sentiment in this way.

“When others reduce your entire identity to a simple facial feature, it can have a lasting psychological effect. “

“Few who regard themselves as members of the mainstream understand what it is like to be ashamed of one’s parents, to be constantly striving to be just like everyone else without ever being able to fit in. “

“Perpetual Foreigner” is also a point that has been mentioned several times in the “Stop Asian Hates” campaign that began in the US in March 2021.

Many Asians feel that they have faced this dilemma of not being accepted by mainstream society since before the Covid-19 epidemic broke out. ‘You don’t belong here,’ ‘Go back to your own country.’ The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic only exacerbated the problem.

Why they just don’t understand? We are all the same, we all have blood, flesh, bones and we all make mistakes,” Christopher says.

But compared to the support and campaigning for the ” Black Lives Matter” protests in 2019 following the death of African American George Floyd at the hands of police, the Asian protest groups have a long way to go. Shouting “Stop Asian Hate” is just the first step.