In the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine, how has the conflict affected the lives of Russians living in the UK?

Maxim had two choices. Go home to Moscow and risk arrest and a possible prison sentence or seek asylum in Britain. He was confident he could go home unscathed, he had nothing to hide, and he had done nothing wrong. His wife, Eugeniya, was convinced that his innocence may not spare him from a Russian jail cell. With just minutes until departure from Heathrow, the decision needed to be made.

They calculated the risks; two different paths could lead to two very different outcomes. With that in mind, they approached the Police at the UK border. Asylum and a new life in Britain had begun. The role his wife had in convincing him to stay in Britain was not lost on Maxim, “Now, with the information what I know, my wife saved my life,” he says.

Two and a half years later and since invasion of Ukraine, protests had sprouted up across the UK. At one such demonstration I saw Maxim speaking to the crowd. His large, broad stature leaned over the demonstrators as they wielded home-made anti-war placards and displayed blue and gold colours that cut through the grey March sky on Cardiff’s busy high street.

Maxim and Eugeniya regularly attend demonstrations. they feel that Russians outside the Russian border have a responsibility to speak out against the conflict.

“I believe that Russians must do everything now to stop the war. They can support the Ukrainians, they can come to the protest, they can share this information they can say their opinions on the internet…they can do anything to stop the war,” says Maxim.

The Russian government has come down heavily on anti-war demonstrations. Alongside Maxim’s boss being imprisoned for three years on what the couple describe as unlawful charges, leading to their asylum, Maxim and Eugeniya appreciate the risk that comes with political dissidence in Russia.

However, they are not alone in their opposition to the invasion. Vitalijs a Latvian born Russian, now living in Warwickshire, also deeply condemns the war. He describes how the conflict has taken a profound emotional toll on him, “My manager asked me if everything is ok… I just broke, I just couldn’t stop crying…. I just couldn’t hold my tears anymore,” he says.

During the start of the initial conflict in Ukraine in 2014, Vitalijs was able to look at the case put across by his fellow Russians, however the invasion quickly changed this. “After 24th of February, I was just switched off [Russian] television completely, and I was looking into what exactly was going on from the Ukraine point of view.”

His views on Putin have also shifted, “I have changed my views dramatically since all of that started, everyone has viewed Putin as the saviour of the Russian Federation,” he continues, “You can’t just go and bomb an independent country… because you want them to be with you or you don’t believe they’re supposed to have their own path.”

Despite his disdain for the Russian government, Vitalijs still finds the footage of Russian soldiers being killed incredibly difficult. “I couldn’t calm down for a few weeks… especially seeing people from both sides and especially from the Russian side being killed,” he says.

NATO believes 7,000 – 15,000 Russian soldiers have been killed. Despite the death toll, some Russians believe that this is a necessity.

“I don’t like it but… I support it, and on our protest, we say provide missiles, stop the Russian army … the faster the war ends the faster people stop dying,” says Maxim.

I don’t mind if I’m from this country, it doesn’t mean I’m related to those people

Eugeniya

Maxim and Eugeniya are aligned on their condemnation of the invasion and their support of Ukraine. However, their opinions differ when it comes to sympathies for the Russian soldiers. Eugeniya’s mild, soft voice does not mask that she has a harder sentiment on this subject than her husband.

“It was sad because they all were saying they were almost children, 18 years old. So, they were saying we didn’t want to go to Ukraine, we didn’t know we’re going to Ukraine. And I believed that because I know it often works like this in Russia,” she continues, “I don’t believe this anymore. They will know where they’re going, so, it’s fine. If Ukraine would attack Russia, I will be the same against Ukrainians … I don’t mind if I’m from this country, it doesn’t mean I’m related to those people.”

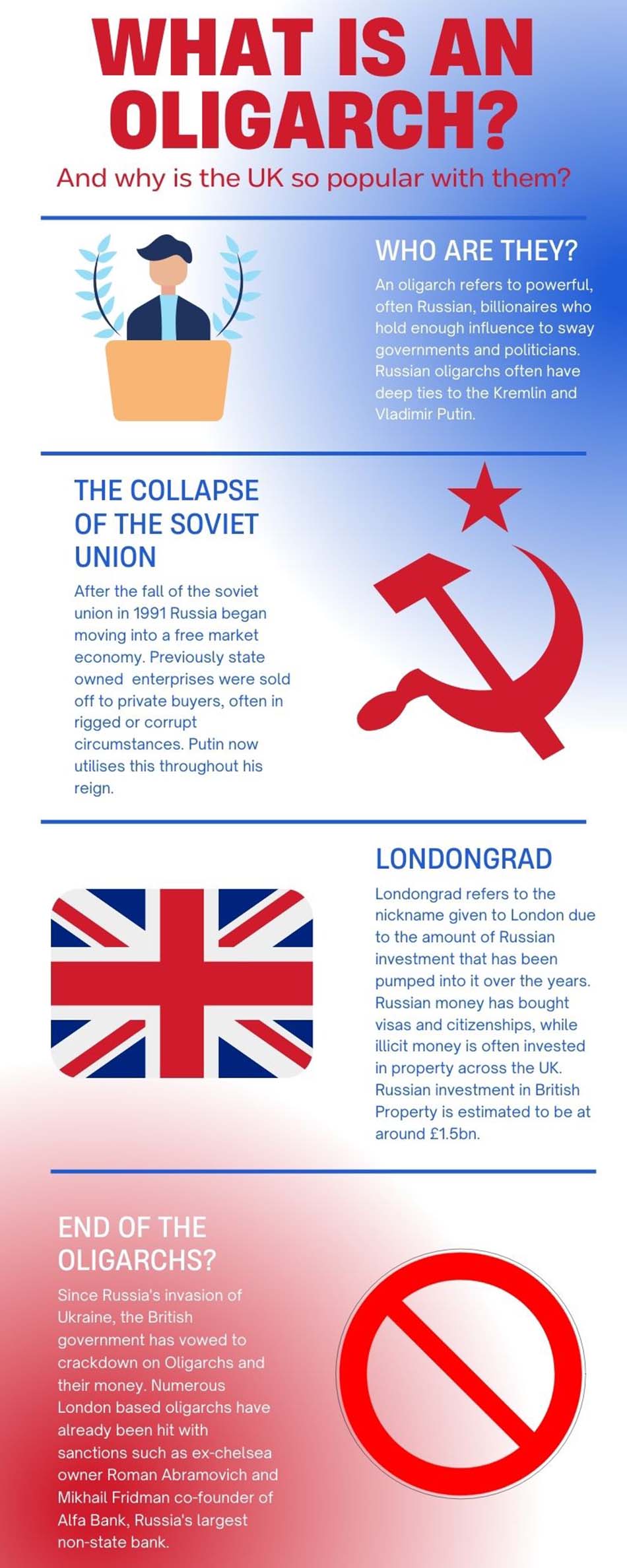

While the western world continues to arm Ukraine, wealthy Russian oligarchs in the UK, with suspected ties to Putin, have been hit with heavy sanctions including asset freezes and travel bans. London has long been a city where oligarchs have invested their wealth, leading to some, including Maxim, referring to the capital as “Londongrad”.

However, measures such as the economic crime bill, set to be introduced later this year, aim to stop overseas assets being hidden through properties in the UK.

Eugeniya finds it unsettling that these people have been welcomed into the UK, “We just don’t like these Russian oligarchs here. They were invited. The oligarchs here were given them visas.” She said, “we know where this money came from. They came from the killings, from the military. They sell the weapons. They sell drugs.”

However, Olia, a Bulgarian-born Russian, believes Russia is being seen unfairly in the eyes of the UK, “There’s a lot of unneeded hatred… towards Russians, and they are really being made to look like the villains of the world,” she says.

Despite living in the UK for over half of her life, Olia stands firm in her views, “In my political views, you can consider me Russian 100%,” she says.

“I think war is the worst thing that can happen. It’s devastating. absolutely devastating. But all the Russians are doing is they’re protecting the Russians in Ukraine,” she says clearly and purposefully.

She is also confident of Putin’s leadership and intentions, “I genuinely think he is a very, very clever guy. I think he’s looking after his people,” says Olia.

Across the UK, support is shown for Ukraine, from flags in front gardens, to Facebook posts, to protests and demonstrations in town centres. Olia counts herself in the minority in this respect, “I’m surrounded by people that have the other side of the argument. And this is what makes it more difficult for me, because I feel like I’m a lone wolf,” says Olia. “I’m too scared to speak out, because I’ve got completely the opposite view.”

I think the overall opinion of people in England is that the Russians are just crazy and they slaughter people

Olia

Olia recalls a moment at the gym where someone asked, ‘you’re not Russian are you?’, and though she does not feel discriminated against, she feels the opinions of British people towards Russians are unjustly harsh, “I think the overall opinion of people in England is that the Russians are just crazy and they slaughter people,” she says.

To live peacefully, Olia feels she must not allow her views to impact her relationships. “I don’t let these things affect my life…I’ve had a few tiffs with people. But I’m not ostracised, because all of these people, I’m still friends with.”

Vitalijs has found himself butting heads with family and friends, not least with his older brother of whom he had a serious argument with over the phone during the first days of the war. However, when it comes to family, he too sees a necessity to leave war and politics out of the conversation. However, outside of his family, relationships can be more vulnerable.

“I’m always going to find common language with my brother, but people who are not so close to me … my friends, I just lost the contact with them and do not talk with them anymore,” he says.

Vitalijs knows his views make him an outlier, “It is difficult to accept that you are on your own in such waters,” he says.

However, in the UK, he is not isolated when it comes to his disregard for Russian media. In March, RT News, described by UK culture secretary Nadine Dorris as, ‘Putin’s polluting propaganda machine’, was removed from UK televisions.

“To be Russian is one thing, and to be a Patriot is one thing, and to support the government is another thing

Vitalijs

To Vitalijs, Russian ‘propaganda’ is the cause for his family’s way of thinking and is an effective tool in the Russian arsenal. “It is really horrible weapon… because people who watch it and who believe in it, they are just blindfolded, brainwashed, and did not see these atrocities, all these killings, deaths of people in Ukraine.”

The information war, however, is not one-sided. Just as the world accuses Russian broadcasters of fake news, so does Olia of western media outlets, “What the media is showing you here is something that it’s a bit like a twisted mirror, you look at it, but the reflection’s completely the opposite of what’s happening,” she says.

Despite conflicting opinions between Russian speakers in the UK, there is still common ground to be found in the idea that identity is not created by the decisions of governments. “To be Russian is really, really difficult. You need to be able to divide to be Russian and to support the Russian government,” says Vitalijs. “To be Russian is one thing, and to be a Patriot is one thing, and to support the government is another thing.”

Olia feels her grievances lie with the British government, not her neighbours. “Britain is not exclusively the government. I feel like I belong with the people. But I don’t feel that I belong with a government,” she says.

However, as common ground seems out of sight in war-torn Ukraine, Maxim and Eugeniya build their lives in the UK, they continue to protest the invasion, safe in the knowledge they will not see a Russian prison cell. “I feel very good. United Kingdom, it is where we’re okay,” says Maxim.

With Britain as their new home, Maxim, in his deep voice and thick Russian accent he radiates with positivity when he talks about his future. “Yes, we’re really hopeful about it. And so, looking for a lot of plans.”