China’s Emerging economies have put a threat to skilled craftsmen, especially those who moved from rural areas. Will they change their jobs for a living?

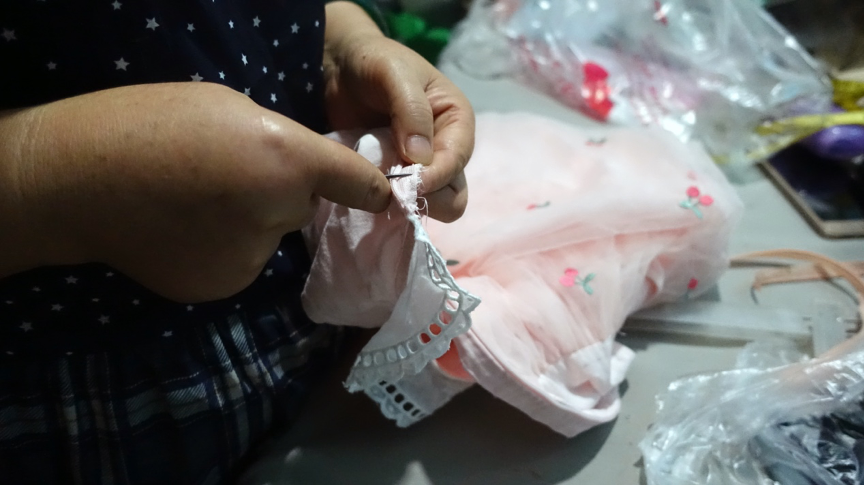

With the sound of a sewing machine, Qin Zeng begins her day at eight in the morning. This is her battlefield; the enemies are those clothes. The first step she took into this field was thirty-five years ago, and she has never looked back.

‘I came to Chengdu from a little village when I was 18,’ she said. ‘and I realised that I should stay here, no matter how hard it was going to be.’

Before Qin was eighteen, the farthest place she had been was the Central Square in Ma’an Town. She had never dreamed that she’d make it to the big city. But in 1985, with her excellent sewing skills, she landed a job with the Chengdu Textile Factory and became a textile worker.

However, it is hard for migrant workers to have a stable job in cities and besides, the prosperity of the textile industry did not last long.

According to the Global Times, China’s textile industry developed rapidly from 1980 to 1997, with the total number of cotton spinning spindles growing from 17.8 million to 42.45 million.

But over time, the textile business was hit by too much competition in the market, a slump in profits and a workforce that was too big for the available work. Since 1992, state-owned textile enterprises have experienced big losses. In 1996 alone, they lost 10.6 billion yuan.

Credit: Changsong Liu

So, in 1995 Qin was forced to leave the textile factory because of the slump in business. She was faced with two choices: either stay in Chengdu with the real possibility of having to change jobs or to back home to the countryside and work the land. She chose the former.LiaoWang, a news journal sponsored by Xinhua News agency, shows that Chinese migrant workers have gone through different stages of development in the past 40 years.

Each stage has allowed migrant workers to explore city life and gradually become citizens. This group of people has transferred their jobs from labour to skilled. They are no longer called ‘migrant workers. Over time they have become known as ‘urban migrants’.

At that time, Qin and her husband rented a shop after they left the textile factory. She began to design and sew clothes for customers and became a professional tailor. Since then, Qin has worked 12 hours per day. She sews around 50 pieces of clothing every day, sometimes more than a hundred. And she’s been here in this shop for more than 20 years.

“Working for others is not a long-term solution, after all, you have to do it for yourself,” Qin said. This is the typical spirit of migrant workers: Be brave and never give up!

However, as new technologies shape the world of work in different ways, new forms of employment and social platforms gradually become an important engine for stable economic growth. For example, some traditional industries such as offline retail and manual manufacturing have been greatly affected. Consumers in China have gradually begun to pursue fast and convenient life experience.

Zhang Chenggang, the director of the China New Employment Form Research Center, Capital University of Economics and Business, said to Sohu News, ‘China should support the development of new forms of employment and its related sharing economy platforms with an inclusive attitude.’ Indeed, China has chased up this opportunity. The advent of the global digital economy has stimulated new demands and greatly increased the frequency of people shopping online.

Many offline retailers are moving to online platforms, adopting new ways to interact with customers. In this year’s annual report, Alibaba — one of China’s biggest e-commerce operators — revealed a staggering 960 million active consumers.

“The new employment form not only provides a large number of job opportunities but also presents a distributed effect, which helps to slow down economic and employment fluctuations,” said Weiguo Yang, Dean of the School of Labor and Human Resources of the Renmin University of China, according to Zhejiang News.

Yang points out that offline consumption is now declining. At the same time, online consumption is growing exponentially, and new forms of employment have become prevail.

The report on China’s Sharing Economy Development (2020), issued by the China National Information Center, reveals that the number of employees on platform companies that emerged in the form of new business models reached 6.23 million in 2019, a year-on-year increase of 4.2%. Also, the number of jobs driven by online platforms reached about 78 million, an increase of 4% from the last year.

Credit: China National Information Center

Lei Yan used to be a physical clothing store owner. Since graduating from university in 2006, she has moved from her hometown Fushun to Chengdu to start a clothing store business.

In the first two years of working for the clothing store, Yan had to take the early morning bus to Hehuachi (Chengdu Retail Market) every day to buy goods. She chose clothes in that retail market from 2 to 4 every morning and brought them back to the store for the second day’s sale. “There won’t be many customers when the weather is bad,” Yan said. “Sometimes we did not sell as much as we expected. We have to take a loss.”

But since the e-commerce gradually emerged, Yan and her friends launched online Taobao shops, and the physical store was closed. The online store’s sales far exceed the previous physical one.

Yan said that she used to rely on physical labour since she needed to carry her clothes back and forth to the stockroom. Sometimes she would be on her feet all day in the shop. All that is a thing of the past and today, she says she relies more on instinct and nous. She believes she will learn how to become a good operation manager for online shops.

Nowadays, young people are keen on online shopping. Various online shopping festivals and live-stream service launched by China’s well-known e-commerce platform Taobao are constantly promoting young people to spend money online.

According to Finance China, live-stream service has become a new engine for e-commerce development.

China’s business big data shows, e-commerce live-stream platforms in China has exceeded 10 million in the first half of 2020, the number of active live-stream platform anchors has surpassed 400,000, with more than 50 billion views and 20 million products on the online shop shelves.

Jiaqi Li, who born in Yueyang, Hunan, was just a behind-the-counter shop assistant for L’Oréal in Nanchang, a second-tier city in China before he became a household name.

In 2016, he chased an opportunity.

Li created his online empire on Alibaba’s live-stream platforms by selling lipsticks. His slogans and tips have made him “the King of Lipstick in China”.

Credit: CGTN

During Li’s live-streaming shows on Taobao, he attracted an audience of more than 36 million. He even managed to generate more than $145 million in sales, with only five minutes spent on each product.

The staff from the live-stream platform team said that the e-commerce platforms are regarded as a means of promotion by merchants. That is because all the online shops will refer to factors such as product search rankings and sales volume, and the form of live-stream service has brought people’s attention to their products.

Li has transformed his life by chasing the on-going trend. Meanwhile, this selling mode has reshaped the shopping behavior of young Chinese consumers.

“I’m too busy at work to shop around. But it is easy for me to watch live streaming rooms and decide what to buy even when I am on the subway on my way to work,” said Ms. Wei, a white-collar worker who works for a financial company.

Indeed, more and more dot-com companies in China such as Taobao, Jingdong, Suning, have diversified their service from offline to online and have launched their online shopping apps for customers to provide with the high-quality and efficient shopping experience.

Behind the scene of the rapid development of new employment patterns and the changing shopping behaviour of consumers, Qin, in her 50s, has met the biggest challenge in her life.

She thinks that she cannot adapt to the new e-commerce trend quickly. But she’s also afraid that even though she’s worked hard all her life, there may be nothing to show for it in future.

Qin began to think about the development of her shop under the current circumstances.

During the coronavirus epidemic this year, Qin had to close her shop for two months in line with the latest policies of the local government.

“I can’t close the sewing shop forever.” Qin said, “My daughter is still studying abroad, and I have to earn more money for her tuition fees.”

She started sending her physical store addresses to customers for the first time via WeChat (China’s social media software) and received some clothes that needed to be sewn. In this regard, Qin said that she can work more efficiently.

In March, Qin’s shop was finally re-opened for customers, she said more and more customers have been bringing their clothes to her shop. Since the coronavirus lockdown restricts shopping behaviour, most people switched to online platforms to buy clothes. But they cannot try on clothes that they want to buy immediately.

As a result, most shoppers end up sending clothes back if they don’t fit. However, a growing number are seeking out skilled tailors to alter the clothes to fit.

“There is always a way out,” said Qin.

When she was asked if she would consider starting an online business in the future, she smiled and said, “I just want a better life, and I will fight for it.”