Deprived of the slightest touch, millions in lockdown feel what psychologists refer to as ‘skin hunger,’ humans’ primitive need for physical contact. But in a forcibly touch-less world, do we crave something deeper?

It was day 48 when Perrey Lee finally cried. Or 50. Whichever day it was since March 15, the last day she touched a human.

Lee, who lives alone, was doing it all: she jogged, meditated, groomed five chickens, walked her dog and nurtured saplings. She chatted with the neighbours, Zoomed her family and every Saturday morning, just barely, she grazed the hand that passed her coffee from the drive-thru window.

But on 1 May, 45 minutes into the Iceman Special’s livestream dance party, the 45-year-old lawyer abandoned her fellow dancers in their virtual Houseparty app. She watched the remaining set alone from her living room until her favourite band too signed off into virtual oblivion.

Then, sitting on her couch, Lee cried.

“I hate people who say this is the new normal. It can’t be. Without that — ” Lee touches her skin softly “ — just that little bit, I feel fake. Like I’m not being seen. I’m not actually here. Like I’m not real.”

Lee is one of millions experiencing quarantine’s newest normal: a life hijacked of human touch and an insatiable desire to get it back. Or what scientists refer to as ’skin hunger’, humans’ biological and psychological need for physical contact.

“When you think of skin hunger, you think sex, but this is every notion of touch, every notion of being human,” says Darcy Scoggin, a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) and psychotherapist in New Orleans, Louisiana. Humans are inherently social creatures. Touch, being our most primitive form of communication. “As horrible as any deleterious touch would be, no touch says you don’t exist.”

Skin hunger’s reality is far less sexy than its status as quarantine’s newest slang suggests. The repercussions of going hungry have been pounded into psychological cornerstones for well over a century. It’s why babies in neonatal ICU cling to parents’ bare chests. It’s the reason Canada’s longest-serving prisoner drew blood from his cheek, mixed it with his saliva and dabbed it onto his legs to lure the flies he pretended were his wife’s fingers.

“[Touch] is our model of being,” says Dr. Patrick Sewell, a psychiatrist specialising in addiction and child psychiatry for over 20 years. He notes Romanian orphans‘ lack of touch in early life resulted in permanent physical and cognitive impairment. “We survive, and have survived, through collectivisation and meeting the world as a social unit. The floods of oxytocin and antidepressants bond us.”

Physical touch doesn’t lose potency with age. Touch lowers cortisol levels, bolstering our immune system, hacking stress and anxiety and swamping us with nature’s ‘happy hormones’. It increases trust and generosity in strangers, reduces aggression and directly triggers our sense of pleasure and the urge to make it return. This occurs within milliseconds in both the touched and toucher, even when the touch is unconsciously registered.

I miss the spontaneity of it, the sudden feeling of being human.”

Perrey Lee

In other words, human touch is a two-pronged physiological steroid shot, supercharging the good stuff to keep us calm, sane and connected. Quarantine indefinitely blackballing touch makes for a rather grotesque paradox, particularly coinciding an international rise in one-person households.

“A lot of my clients come to me because that’s their only sense of touch,” says Candy Welch, a licensed massage therapist and owner of Focus Massage and Wellness. She explains that touch acts as a physical ‘I got you’ flowing from mind to body to body to mind. Keeping in touch physically keeps us in touch emotionally. “Right now it’s a big deal. A lot of ailments have returned. It sets in a little more than depression. A sadness. Something we’re missing in life.”

The glut of physiological perks makes our hunger for skin-to-skin seem obvious. But even those never before desperate to touch now notice inklings of disconnect.

It raises the question: Does our hunger scratch deeper than the surface?

I cried because the attempt to recreate the love experience was so hollow. There was no tangible exchange of energy.”

Perrey Lee

“For us to crave touch, it’s nearly a craving to be acknowledged, our basic human nature to be desired and noticed,” Scoggin says. She recalls clients on the brink of divorce rarely engaging in the scantest of touches. Scoggin assigned a simple task: touch, just once, every day for a week.

“They were two new people,” she says on their return. Touch enabled them to trust and relax, but more importantly, to acknowledge each other. “People don’t realise touch is our body’s language until it’s gone. It’s how we experience each other.”

Though not a couple teetering on divorce, many feel divorced from the world and their relationship with it silently crumbling into obscurity as touch dwindles.

“When the [bank] teller calls me baby, if that was a touch, that’s what I miss,” Lee says. “I miss the spontaneity of it, the sudden feeling of being human.”

Yet, Sewell reminds us that touch, though our most basic form, is only one type of communication.

“We’re complex systems, emotionally, physiologically, socially and everything else,” Sewell says. Our complexity demands complex needs, which in turn create a hierarchy. In this, deficits inevitably barrage our status quo.

The good experience we get is not limited to touch.”

Dr. Patrick Sewell

“Many are finding Covid as a deficit, but this deficit is much larger than just literal touch,” Sewell says. “No talking in supermarkets, no waves to strangers, no casual conversations. It’s limited to all forms of acknowledgement.”

Sewell spreads his arms. On the left, people alone. On the right, meaningful connection.

“This,” he says shaking his right hand, “is where the action is, the quality of life.”

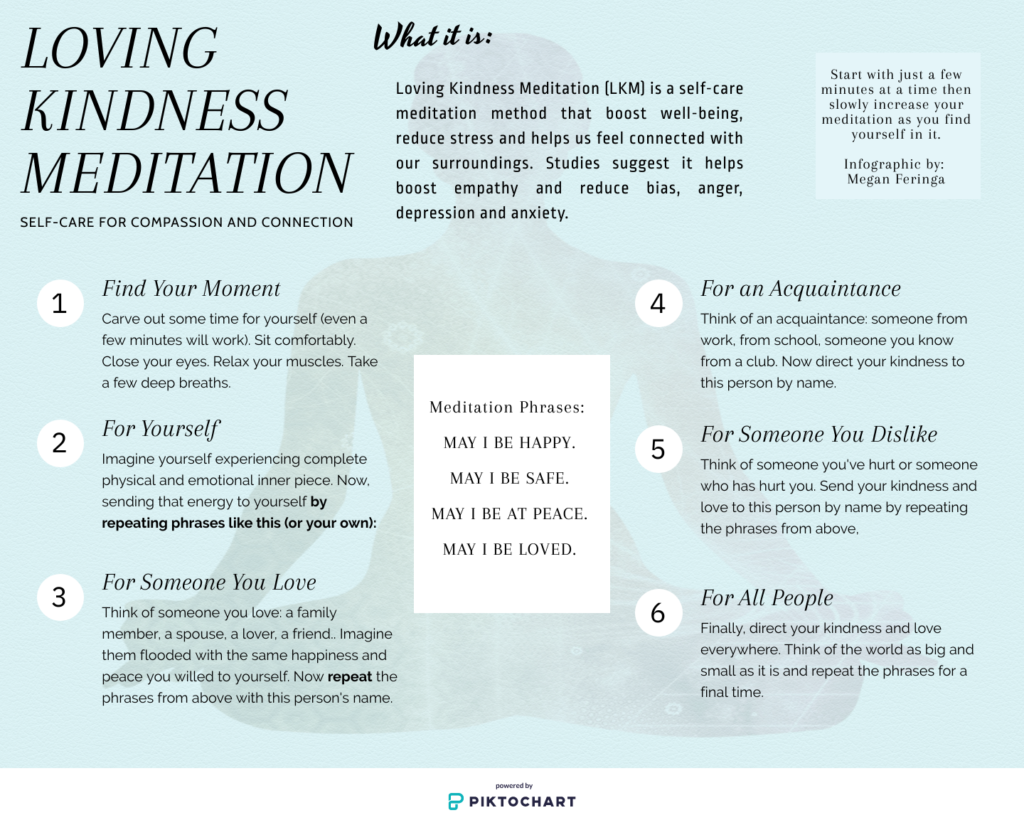

Sating our hunger, thus moving from left to right, requires meaningful connection with another. But that connection doesn’t have to be physical necessarily. Studies show that Loving Kindness Meditation creates the same internal milieu that physically touching does, as do random acts of kindness performed or watched. It depends on our meaning.

“Can you feel me? Can you experience me?” Sewell leans into his camera with a smile. “I could be here remote, detached, impervious, but I’m not.”

How we communicate creates a space, he says. If communication is safe, inclusive and mutual, we feel recognised and valued, yielding the same immune and chemical goldmines derived when we touch.

“The good experience we get is not limited to touch,” he says.

Much can be said for technology’s ability to connect us during the pandemic. Days of geographical constraints are over. But what technology bridges, skin-to-skin still bears a gap, some much larger than others.

“There’s a space we create when we touch, an in-person space you can’t get through a screen,” Lee says. “I cried because the attempt to recreate the love experience was so hollow. There was no tangible exchange of energy.”

It’s why Scoggin doesn’t recommend sex toys and haptic devices to mimic sensations. Toys cannot replicate the subtle verve of exchanged touch, not even a handshake. But we can make our other communications more meaningful. In fact, we might not have a choice.

I know as somebody who would hug a leper before this, I’m now frightened.”

Darcy Scoggin, LCSW

No universal standard for touch exists, nor for skin hunger. Some endure depression, anxiety, or malaise. Some a sense of loss. Others are abjectly recoiling thinking of breaking the two-meter protocol in a store aisle, let alone relishing in what months ago was an innocuous hello hug.

“Everyone has different boundaries. How people perceive touch is based upon those,” Scoggin says. “Boundaries must be respected. This age of Corona is going to really put some fear in people who never had boundaries before. I know as somebody who would hug a leper before this, I’m now frightened.”

Despite texts imploring Welch for a re-open date and her own hands tingling to do so, the last three months are hard to snub: Will she feel apprehensive? Will her clients? How does one promise safe touch while wearing facemasks?

“It won’t be so much getting into the door, but once they get through the door. I don’t know if the feelings will be the same about it,” Welch says.

Despite social distancing restrictions peeling back officially, new personal rules of engagement aren’t far-fetched. It’s a jilting prospect for those aching to return to the raw, impromptu touch of former days reminding them they exist.

“You’re going to have variable degrees of heightened need for support,” Sewell says. “Some people will be incredibly resilient in the face of it. They won’t lose their sense of place and connection with others. Others will be anxious and uneasy, and hence have a real sense of being alone and stressed.”

Then again, Sewell received texts for his birthday in March. He notices more people phoning bygone high school friends, joining online book clubs, and sending the more occasional check-in message. While the climactic ending of millions embracing in a pub might be lost to fiction, our hunger is more than skin deep. Acts of kindness and meaningful connection kindle the physical and relational boons we currently find ourselves dry of, but what if we don’t forget that?

“Perhaps that revival will continue,” Sewell says. “Perhaps a more balanced, connected way of living versus a distracted, stimulatory experience will elicit. Maybe people will catch on. Maybe we will be more aware of our interdependency.”