As indigenous variants of paddy are making a comeback across the Sundarbans’, how is it helping the farmers economically?

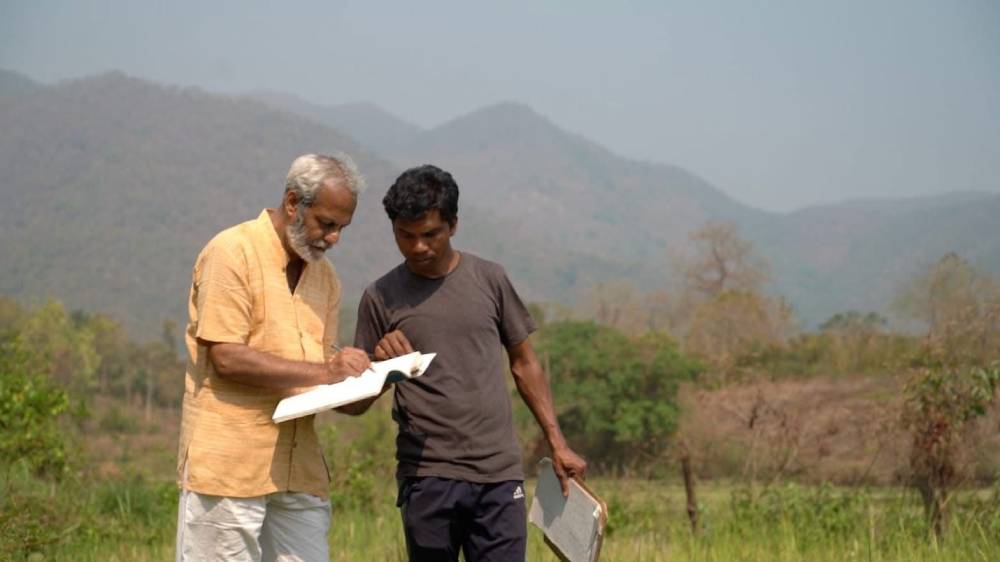

On a humid afternoon in Patharpratima block, deep in the Indian Sundarbans, Somsubhra Sahu rests his weight on a crutch, scanning a muddy paddy field where farmers, mostly women stoop into the soil, planting seedlings in neat rows. The crop is rice, as it has been here for centuries, but not the industrial hybrid varients pushed by government and seed companies. These are Dudheswar, Talmugur, Hamilton—traditional varieties of rice, which could thrive in the increasingly saline soil. These rice varieties, once abandoned but now returning to the delta.

Sahu is not a typical agricultural trainer. He is around fifty-eight, soft-spoken, with the quiet determination of someone who has already fought his battles. A few years ago, he lost a leg in a road accident, while travelling the remote corners of Sunderban to train farmers in the nuances of organic and traditional farming. The injury could have ended his career in the fields, but thanks to his immense will power, he survived.

He recalls crawling up the steps of an agricultural training centre, refusing to let his body dictate his purpose. “An accident and wrong treatment led to the amputation of my leg in 2022. Just a few days after my operation, the block administration requested me to attend a meeting, to train the farmers how to grow rice varieties which can thrive in saline soil. The administration didn’t knew about my condition. How could I miss that opportunity? Even though I had to crawl all the way up to the second floor, I went there and interacted with the farmers”.

He is currently a trainer with the Anandadhara scheme, initiated by the West Bengal government. Launched in 2012, its purpose is to reduce rural poverty by enabling poor households, mostly women to access sustainable livelihoods. In climate hotspots such as the Sundarbans, schemes like these are practically the lifeblood of the local communities.

Coming from a traditional agricultural family in the Durbachati Panchayat area of Patharpratima, Somsubhra is associated with sustainable farming from 1984, just after he left college. Although he tried popularizing the long lost traditional varieties for long, the interest regarding them are comparatively new, all thanks to the almost annual cyclonic surges in this region, starting with the Aila storm of 2009.

“The Amphan storm of 2020 was far more destructive than the Aila of 2009 in terms of livelihood challenges. The flooding was extensive, and it took months for the water to completely subside. After the flood, we noticed that only the traditional varieties such as Dudeshwar, Talmugur etc were able to survive in the stagnant water. All the high yield varieties died off”.

That was the beginning. He experimented with the local farmers. By plating various types of seedlings again and again in the same condition, he came to the conclusion that if the locals have to survive in this situation, they have to mend the way they farm.

However, not only Somsubhra and his team, in the post Amphan period, all the blocks across the Sundarban such as Gosaba, Hingalganj, Kakdwip, Kultali shared similar experience of rice survival. The state government took lesson from that shared experience, and as per current standard operating procedure, after such cyclonic floods, the government distributes only traditional varieties of seed as a relief to the affected farmers.

The soil itself tells the story. Salinity levels in South 24 Parganas district, where Patharpratima is located, have steadily risen over the past two decades. According to studies by Jadavpur University, nearly fifteen per cent of agricultural land has already become barren. For farmers who live on thin margins, this is not an abstract threat but a daily reckoning.

The key challenge that Somsubhra and his team faced, was convincing the farmers to return back to their traditional roots.

At first, many were sceptical. The memory of the Green Revolution still looms large in Bengal. In the 1960s and 1970s, when food shortage was a daily reality in the countryside, high-yielding seeds promised salvation. Farmers abandoned their traditional seeds for the new “miracle” varieties, encouraged by government subsidies and multinational companies. Yields rose, but only in areas with irrigation, fertilisers and controlled soil conditions. In the fragile ecologies of the Sundarbans, the miracle faltered. By the time climate change added cyclones and sea-level rise to the equation, the very varieties promoted as modernity were the ones failing the fastest.

“Now every year, a farmer must buy seeds and fertilizers from the market. Every year the cost of these inputs is becoming costlier, but earning from the farm is decreasing exponentially. As a result, the farmer is entering a spiraling debt trap every year,” said Somsubhra.

To combat that, he tried convincing the farmers that using traditional farming practices, the cost of agriculture can be brought down significantly.

One of those farmers is Namita Jana. After Amphan swept over the islands in May 2020, her fields resembled a salt pan. Nothing grew. “I thought we were finished,” she says. “We bought seeds from the market, hybrids, but they all failed. Only when we planted the old rice, the ones Somsubhra told us about, did the land respond.”

Pegged on by that confidence, she is currently only farming traditional salt tolerant varieties.

Reflecting her experience, she said, “in 2021, one year after Amphan my land became almost fallow. Earlier I used to get 100 sacks of rice from my 10 bigha land, but in 2021 it came down to just 25 sacks. The very next year, I experimented by mixing High Yield varieties with the traditional ones, and my yield increased to 67 sacks. In 2024, I only farmed traditional varieties and got 105 sacks from my land. I am continuing the trend this year as well”.

In terms of cost efficiency she said, “high yield variety inputs costs around INR 30 thousand in my 10 bigha land. And I used to earn INR 70 thousand by selling it. Now using traditional methods and indigenous varieties, the input cost has come down to INR 12 thousand and I earn around INR 80 to 85 thousand from my produce”.

In this method, the farmers preserve a section of the produce as seeds, and they don’t buy seeds anymore. Somsubhra had taught them to use traditional fertilizers made from clay, cowdung etc and that has also helped significantly lower the input cost.

Unlike Namita Jana, the transition story of Asima Sahu was not that easy. Her inlaws couldn’t farm for a whole year after Amphan. The very next year saw another sweet water flood, but decreased salinity of the soil as well. However, even after the floods, the high yield varieties didn’t grow in their rice fields.

In such a scenario, she requested her in laws to try farming the indigenous varients, about which she learnt from a workshop tutored by Somsubhra. But her in-laws were skeptical.

“I had to practically fight my in-laws, and thanks to my husband I was able to farm indigenous varieties such as Dudheshwar and Talmugur in 2 out of our 6 bigha land. Currently I am not only farming our own lands, but I have also taken some additional land in lease, and farming there as well.”

According to her, using natural fertilizers such as cow dung, fermented soil and jaggery has resulted in better yield per bigha than using chemical fertilizers.

The shift from despair to renewal did not happen overnight. It began when Maity crossed paths with Nilanjan Mishra, a PHD scholar from Kolkata who had returned to his native Sundarbans to help with relief work after Amphan. Mishra had set up Patharpratima Runners, a group that started by distributing food and tarpaulins in the storm’s aftermath. But he quickly realised that handouts could not restore dignity. “People were lining up every week for rice,” he recalls. “We thought: how long will we do this? Unless farming itself is rebuilt, relief will never end.”

Mishra and Maity joined forces, bringing their complementary strengths—one with organisational networks, the other with agricultural knowledge. Together, they convinced a group of small farmers to form a cooperative. The idea was simple yet radical: revive indigenous varieties, farm them collectively, and sell the produce directly in Kolkata at fair prices.

This initiative has resulted in the formation of a farmers co-operative named : Dakshin Sundarban Susthayi Krishi o Krishak Samabyay. Starting with around 5-7 farmers such as Namita Jana, currently the co-operative involves around 25 farmers and they farm around 60-70 bighas in total. Along with traditional rice, which is witnessing an increasing demand in the markets of Kolkata and other big Indian cities, they also sell organic vegetables and chicken as well.

“When we first approached them to farm the sustainable varients of rice, they were worried about the yield. That is what they have been conditioned in the past few decades. They only know that high yield means more produce, which will complement their high input cost and continuously dwindling earning from selling those produce. We had to convince them to focus on the price. Farmers can decide the price of their commodity, and earn atleast a living price, was like a shock to many of our farmers”, said Nilanjan Mishra.

In Nilanjan’s vision, ensuring a decent earning of the farmers is not enough. To ensure sustainance, the farmer’s well being should also be taken care of. “Farmers should consume their produce and celebrate it in the first phase. We ensure that during the traditional harvest festivals such as nabanna and also during our monthly meetings, we cook and eat our own produce together.”

According to Nilanjan, in the near future they plan to organize health screening camps to investigate the negative impacts, such as various cancers and respiratory diseases of chemical fertilizers in the farmings families. They also plan to set up processing units and agricultural laboratories to ensure that farming becomes lucrative, not just a mean for sustenance.

In the initial phase, this initiative got help from Debal Deb, an internationally acclaimed ecologist, who distributed free seeds.

“Seeds became commodities,” said Deb, who runs the seed bank Vrihi and alternative farming school in the Niyamgiri hiils of the Indian state of Odisha. “What used to be shared and saved by communities became patented, bought, and sold. Farmers were told to forget their old varieties. But those seeds had centuries of adaptation inside them. They were insurance against exactly the kind of crisis we face today.”

Deb has spent decades collecting and preserving indigenous rice. On his farm in Odisha, he maintains over 1,400 varieties, many of which are shared with farmers in the Sundarbans. “Varieties like Talmugur and Matla can withstand saltwater. Others can survive submergence for weeks. These are treasures, not relics.”

Deb himself had mixed response when he first tried to help the farmers after Amphan in 2020. He distributed free seeds to around 50 farmers, but only 2-3 of them kept those precious seeds and used them. When asked about the difference of yield between the high yield varieties and the traditional ones, he said, “the survival of the land is in question. If the land becomes uncultivable, and saline, where will one farm the high yield ones?”.

Resistance often comes from the family, but women farmers, Somsubhra notes, have been the most willing to experiment. Patient and meticulous, they see beyond one season’s yield to the longer arc of resilience. Today, women form nearly sixty per cent of the cooperative’s members. They not only farm but also help package and market the rice to city consumers who are willing to pay premium prices for “heritage grains.” A kilogram of Dudheswar can fetch twice the price of industrial rice in Kolkata’s organic stores, making the cooperative economically viable.

The state government, for its part, has taken cautious steps toward supporting this shift. The Agriculture Department has distributed some salt-tolerant varieties like Hamilton and Matla, and programmes like Anandadhara encourage women’s self-help groups to take up alternative farming. In 2022, the government announced plans to scale up distribution of indigenous seeds across several coastal districts. Yet activists argue this remains marginal compared to the subsidies and infrastructure still directed towards hybrids and chemical inputs. “The government talks about resilience, but its policies favour multinational seed firms,” Somsubhra said. “The post of agricultural assistant officer is practically non existant across rural Bengal, with a few thousand vacancies. The agents of pesticide and seed companies take their place and misinform the farmers.”

“Before 1960’s people would laugh if anyone told them that seeds had to be bought. But thanks to the green revolution, it is has become a high priced commodity, something which is increasingly getting out of the purchasing capacity of the farmers”, said Somsubhra.

In Patharpratima, however the future feels more fragile. Each cyclone pushes the sea further inland. Each year, more land is lost. For families that survive on a few bighas of paddy, the margin of error is shrinking. And yet, in the small patches where indigenous seeds take root, a different story is visible.

During a recent cooperative meeting, sacks of Radhatilak and Talmugur were stacked for shipment. The rice has a nutty aroma, prized by urban consumers who are rediscovering heritage food. But to the farmers, its value is deeper. “This rice is proof that we can still live here,” Namita says. “When everything else failed, this survived.”

For Somsubhra, the symbolism is personal. He knows what it means to rebuild from loss. His missing leg makes every step a struggle, but he continues to spend his days in muddy fields, his crutch planted deep in the soil. Watching the women transplant seedlings, he smiles. “When I see them succeed, my pain disappears,” he said.

The story of indigenous rice in the Sundarbans is not only about agriculture. It is about sovereignty, dignity, and resilience in a drowning world. The Green Revolution promised abundance but eroded autonomy. Now, in the shadow of climate change, farmers are reclaiming seeds not as commodities but as heritage.

As dusk settles over Patharpratima, the crickets sing and the tide rises in the Matla river, carrying salt further inland. The future here is uncertain, but the fields shimmer with young shoots of rice, stubbornly green against the odds. Somsubhra leans on his crutch, his gaze steady. “We cannot control the sea or the storms,” he says. “But with our seeds, we can still control our hunger. That is our power.”

For him, every grain of Dudheswar or Radhatilak is more than food. It is memory, resistance, and hope—a reminder that resilience often begins with the smallest of things, nurtured in the hands of those who refuse to give up.