Anti-protest laws have sparked global debate, so why did the UK decide to crack down on activism, and what lead to this decision?

Louis sprinted onto the football pitch, his heart racing as nearly 40,000 spectators watched in stunned silence. With a metal zip tie in hand, he quickly fastened himself to the goalpost during the Everton vs. Newcastle Premier League match. His bright orange shirt, reading Just Stop Oil, stood out amongst the blue and white of the angry crowd behind him.

This dramatic scene was just one of many eye-catching moments from the environmental protest group Just Stop Oil, which has dominated headlines across the UK since its inception in 2022. Louis McKechnie, 24, joined the campaign that same year. His actions, along with those of others, have sparked intense debate over protest rights and public order.

Just Stop Oil’s dramatic pitch invasion, in March 2022, was a calculated move designed to maximise impact, “We thought over previous campaigns and what they were missing and one thing that we’d always known is to propagate an idea through society most effectively requires two things. It requires the idea to be controversial and heard by the most people possible. If everybody agrees with what you’re saying, it’s not going to be propagated. People aren’t going to talk or debate if they agree,” says Louis.

You probably recognise them by their bright orange paint, whether they’re spattering it on priceless art or blocking traffic on the M25. Just Stop Oil has made headlines with their bold and controversial tactics, all in a bid to pressure the British government into ending new fossil fuel licensing and production.

The growing visibility and disruptive nature of Just Stop Oil’s protests have prompted a strong government response. The UK government introduced the Public Order Act 2023. This new legislation aims to limit such protests by criminalising many of the methods employed by Just Stop Oil, including high-profile actions like the one Louis staged.

Louis views this response as a sign of the group’s impact, “These laws and acts were brought as a sort of reaction to our protests and our campaigns. But that I believe in itself that is evidence that the tactics and protesting campaigns we’re using are effective and actually threaten their power and control. The whole model is generally first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win,” he says.

This is when Just Stop Oil settled on the perfect target, “So the idea of cultural disruption was created in our circles and what has the biggest following in the country? It’s football. It is the cultural phenomenon with the highest rate of emotional attachment to something that has regular events and is in the mainstream consciousness more regularly and more strongly than anything else,” Louis says.

Recognising this, the group decided it was time to escalate their tactics. Louis continues,“We decided it’s time to use some new tactics and try some new things. We’ll try, to throw mud at the wall until something happens. Until something sticks. This felt like it had the potential to have more social influence than any other tactic previously tried by nonviolent protesters, in recent history in the UK, at least.”

So, Louis sprinted onto the pitch and locked himself to the goalpost—a tactic used by protest groups like Extinction Rebellion and Animal Rising. Louis recalls, “my aim was get to that post and get locked on as fast as possible, so I just ran as fast as I could at that point, I wasn’t feeling fear, there was some adrenaline but it felt like pure focus at that point, oddly similar to a meditative state. So I locked onto the post and soon after that, it felt like job done, I guess it was at that point, I couldn’t even hear the crowds anymore.”

For his actions, Louis received a six-week prison sentence and was charged with aggravated trespass. District Judge Wendy Lloyd, who handed down the sentence, described his actions as ‘reckless’ and ‘potentially very dangerous.’

The protest sparked widespread debate and media coverage across the UK. However, public opinion was largely against the group. A 2023 YouGov survey found that while 17% of respondents viewed Just Stop Oil’s actions favourably, a significant majority of 64% held an unfavourable opinion of the campaign group.

Tom Harris, who is an activist, sees this public backlash as a calculated move by the government. “I think they (the Government) saw a great opportunity to turn the public against radical protests or any more protests because it stops us looking at what they’re doing; it’s far easier to kind of point the finger at Just Stop Oil being the problem rather than to acknowledge that the people Just Stop Oil are protesting about are literally setting our world on fire,” he says.

For Tom, protest is deeply ingrained in the UK’s cultural and historical identity. “The kind of working-class radical history of Britain is something we should be proud of,” he says, reflecting on movements like the suffragettes, the Luddite revolution, the miners’ strikes, and the founding of the RSPCA. People now see protests as like a dirty word, even like unionisation and striking—working-class people are against these things that we should be so proud of, and we have to defend it, verbally and physically,” he says.

Despite this, as Just Stop Oil continued to escalate their protests, the government was already taking steps to tighten its grip on public demonstrations. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 (PCSC) marked the beginning of this clampdown, which culminated in the more stringent Public Order Act 2023.

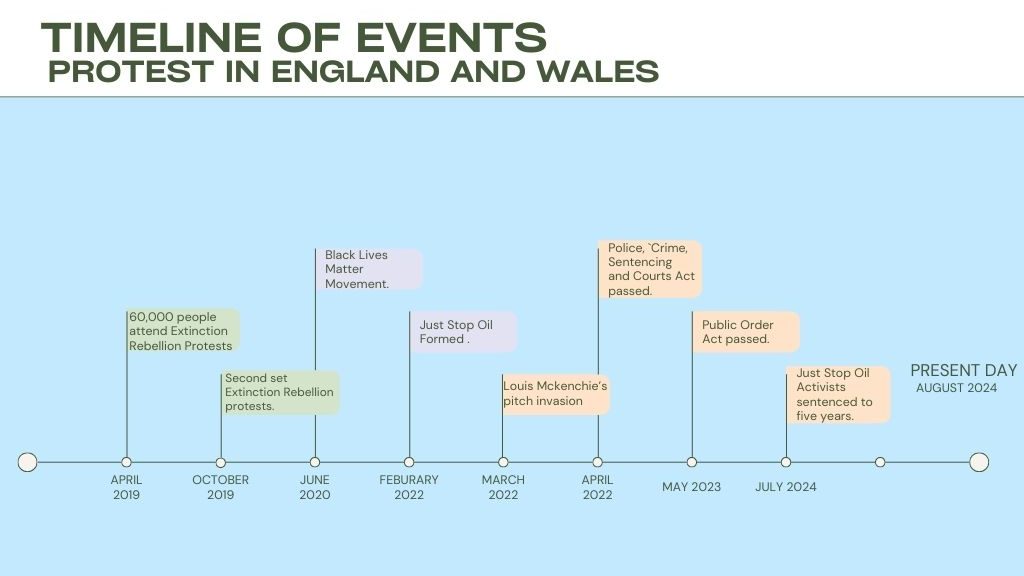

Kevin Blowe, a member of The Network for Police Monitoring (NETPOL), explains the broader context that led to these laws. He notes that the groundwork for the government’s tougher stance on protests was laid back in 2019, a time when political turmoil over Brexit dominated the Conservative Party’s agenda, and Labour was in disarray. Simultaneously, there was a growing urgency to address climate change, leading to a surge in civil disobedience. “This culminated in the huge protests organised by Extinction Rebellion in April and October that year,” says Kevin.

Extinction Rebellion are an environmental campaign group who occupied many key areas of London in 2019. Over 60,000 people attended in an act of mass civil disobedience. They demanded the government ‘act now’ in order to tackle the climate emergency.

Extinction Rebellion’s bold tactics—blocking roads, “locking-on,” and embracing mass arrests—pushed the authorities to their limits and exposed significant flaws in their response strategy. Kevin explains, “the protests were significant because it was a humiliation twice for the Metropolitan Police. Firstly, they got a mauling from senior police and from the right-wing media for failing to crack down on the demonstrations in April. Then when they did decide to crack down, the High Court said that they’d acted unlawfully, and that became the catalyst for immense pressure from the senior levels of policing to introduce this legislation,” he says.

This intense pressure resulted in the introduction of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022. However, as Kevin observes, the government’s response didn’t end there. “The government then fails to get everything it wants and just introduces another piece of legislation; it’s just a knee-jerk reaction,” he explains. This led to the passing of the Public Order Act 2023.

Critiquing these new laws, Kevin argues, “Most of the legislation is poorly worded. It really felt as though it was a reaction; the government was simply looking to have something done because it had, in particular, a cultural war, a kind of aggressive opposition, firstly to climate change activists, but this was also partly due to the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020.”

Yet the introduction of these laws didn’t go unchallenged. They sparked a new wave of activism under the banner of “Kill the Bill,” as thousands took to the streets to fight what they saw as an attack on human rights. Despite the widespread outcry, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act was enacted in April 2022, quickly followed by the even more restrictive Public Order Act in 2023.

Both acts specifically targeted techniques utilised by Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion such as ‘locking-on’. “The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 was focused on giving the police the powers and tools to more effectively neutralise, repress and use intimidation tactics on protests or protesters they deem too effective to be allowed to continue existing. Then the Public Order Act 2023 clamped down on protesters even further, taking away as many of our legal rights as possible,” says activist Louis.

The factsheet that explains why the government proposed the Public Order Act 2023 explicitly refers to Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil are reasons for the legislation.

Louis knows the stakes firsthand. He used the controversial “locking-on” tactic during the high-profile pitch invasion, determined to make a statement. “I was using a plastic cable tie with strong steel on the inside; it was a bicycle lock that was meant purposely to look like it was a lot weaker than it was,” he reveals. “That’s why it took them so long to remove me.” This tactic has a long history in protest movements, but the new legislation aims to make it much riskier for those willing to push the boundaries.

While the Public Order Act 2023 has sparked fierce debate, not everyone sees it as a game-changer for the right to protest. Legal expert David Mead, who specialises in civil liberties and protest, suggests that the impact of the legislation may be overstated.“Most of the things that are in the Public Order Act 2023 were probably captured by other pieces of legislation,” he explains. “In other words, the gap that it’s filling is very small.”

The human rights organisation Amnesty International also hold the view that police already have ‘sufficient powers to manage protest safely and to prevent violence or other serious criminal activity’.

David acknowledges that protests are by nature disruptive, and finding the right balance is crucial. “It’s undoubtedly the case that a lot of people do get very inconvenienced and angry at the M25 being blocked for seven hours or people slow marching through London or other major cities. This has obviously caused trouble for people,” he says.

But the real question, David argues, is whether the solution lies in the expanded powers now available to the authorities. “I think there is a need for balance,” he continues. “I don’t think anyone would disagree on this. The police and the government would always say we protect people’s rights to protest peacefully. The question is, where is that balance properly struck and by whom is it properly struck?”

This question of balance has come into sharp focus with the recent, highly controversial decision to impose unprecedentedly long sentences on five Just Stop Oil activists. Roger Hallam, a co-founder of the group, was handed a five-year sentence, while four others received four-year terms.

They were convicted under the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 for conspiracy to commit public nuisance in connection with a video Zoom call that those prosecuted had attended.. These sentences are the longest ever handed down to non-violent protesters in the UK.

In comparison, the average sentence in the UK for violence against the person is 1.7 years and theft offences just eight months according to a report published by the data group Statista.

David describes these sentences as “unbelievably disproportionate.” Reflecting on how the legal landscape has changed, he notes, “A couple of years ago, you’d be advising protesters that even if you go on this action and get arrested, you’ll probably get a suspended sentence; you might get a month inside if you’ve committed two or three offences, as a sort of slightly tokenistic gesture, but you’re really not going to be spending lots of time in prison.” The activists are now expect to appeal the sentences in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). “I’d be absolutely gobsmacked if the ECHR decide they are proportionate.”

David further comments on the broader trend over the past two decades, noting that “in the last 20 years, there hasn’t been any piece of legislation that sort of facilitates or makes it easier for people to dissent and to protest. Everything else since the Human Rights Act came into force in 2000…has been adding layers of criminal offences or policing power.”

He continues, “so it seems to me even at the most basic level, it would be fairly easy to suggest that the balance hasn’t been struck because if you’re loading one set of scales repeatedly on one side, the balance is going to go. Either the balance was wrong in the first place, was far too favourable to people protesting, or at some stage we’ve reached an equilibrium and we’ve now gone past it.”

Louis expresses his outrage at the severe sentences handed down to his fellow activists, “five years in prison for going on a Zoom call and thinking about a protest and asking people if they’d be interested in partaking is absolute insanity. It shows the state’s desperate; it shows that they’re losing control and they don’t know what to do. They were trying to send a message of strength, that they will not stand for us. But what it really is a message of fear, they’re scared of the fact that they’re not pulling all the strings,” he says.

Louis also foresees an increase in imprisonment for activists, he says, “we’re going to see a lot more of our friends and loved ones go to prison, yeah we’re going to see a fair amount of people going to prison who didn’t even really partake in these protests just because by giving us the impression that they don’t care how involved we are, they’ll go for anybody – it’s an intimidation tactic that they’ve relied on historically.”

Given these concerns, Louis has decided to step back from direct action due to the heightened risks, “I’m terrified for the next 5-10 years, even the next year. I expect to see the majority of my friends get sent to prison with heavy sentences for acting out of love and kindness for all beings and all life. Because they can’t stand the injustice anymore and they’re gonna get hit hard for it. There’s a fair chance I am as well at this point. I would probably say I have about a coin flip odds of staying out of prison for the next year or two at best, and that’s even if I’m not that’s even with me not actively participating in protests.”