One in five UK adults have expressed worry about their body image as a result of images used in advertising and on social media. Are fitness influencers serving their readers best interests at heart or are they making use of their online platform for personal gain?

Jennifer can still vividly recall the incessant taunts from her bullies at school, who always made her feel unworthy. Their harsh insults lowered her self-esteem to the extent where she no longer felt safe being her genuine self in public and pushed herself to disguise who she truly was.

Now, when she scrolls through her Instagram feed, Jennifer McKenzie is bombarded with posts telling her how many calories she should consume each day or how she may achieve the ‘ideal’ body. The endless images of thin, toned bodies followed by messages telling her how she should look, bring her back to a time when she didn’t feel valued.

“I adopted the belief that I wasn’t good enough, that it wasn’t safe to be in the world, and I had really bad anxiety because of the way I looked,” said Jennifer, who had always been an active child but when she gained weight as she grew older, felt pressure to look and act a certain way. “You must look younger, you must look slim, you must please everybody before yourself. These were the messages that I got when I was younger as a teenager and going into my early 20s, and I actually started taking weight loss pills. I was starving myself and overexercising because I didn’t want to be fat, because I thought fat made me unworthy and unlovable.”

Jennifer, who now works as a life coach specialising in anxiety, shared that social media’s emphasis on objectifying women’s body shape caused her to feel under pressure to meet unattainable body standards. She said, “I think the pressure to be skinny and tying our size to our health, just because you are slim, doesn’t mean you are healthy.”

The pressure to be perfect became so overpowering for Jennifer that she sought to change her appearance and take drastic measures that endangered her life. She said, “I would have all sorts of beauty treatments because of the fear of getting older, because the message was you’re not good enough and when you get older you have to be young and fit…it actually drove me to self-harm. Being really unhealthy, I got down to a size six because I started taking amphetamines and not eating, so it was a really bad time.”

It shows a reel of people’s lives, and they could be lying about how much money they make and lying about how happy they are

Jennifer Mckenzie, Life Coach

People should be more wary of the intentions behind the information that fitness influencers offer with their followers since they only show them what they want them to see, according to Jennifer. “Things like promoting ‘once you’ll lose weight, you’ll be happier’, it gives a false representation of life in general, because we only see people,” she said. “It shows a reel of people’s lives, and they could be lying about how much money they make and lying about how happy they are.”

While the intention behind many of the images posted by fitness influencers on Instagram is to motivate you to lead a healthy and active lifestyle, recent research reveals that these images of muscular figures have a negative impact on people’s perceptions of their bodies and their self-esteem. According to the Mental Health Foundation, one in five UK adults have expressed worry about their body image as a result of images used in advertising and on social media.

Fitness influencers typically portray a lean, toned figure as the ideal, but being skinny doesn’t always guarantee you are healthy. Dr Jade Parnell, a Research Fellow at the Centre of Appearance Research, questions social media influencers’ intentions regarding their promotion of what they consider to be a healthy body, saying “they do promote that if you’re healthy, you are stick thin and I think there’s issues with that when realistically you could be a bigger size but be way healthier. They take it at face value, they see the outer shell and then they say you’re overweight or you’re not healthy, and it doesn’t work that way.”

To help combat the negative impact of social media, fitness influencers should aim to create content that spreads positivity and encourages others to accept all body types, according to Dr Parnell. “For people who are fitness influencers, trying to include and promote other fitness influencers who represent different body types would be very helpful and there are also self-compassion quotes which we find can be quite helpful,” she said. “It leads to greater body acceptance and appreciation.”

While much of the mainstream media portrays unattainable beauty standards in the form of photoshopped celebrities, it is more widely acknowledged as a production. When you see a model on the front cover of a fitness magazine, you know that a team of people are working behind the scenes to design and create the picture. However, social media influencers establish their platforms entirely on their own, with no professional assistance.

Many people find social media to be more harmful because it is easier to be convinced that what influencers are sharing is a real representation of their life. Amy Elizabeth, a personal trainer from London, said: “With fitness magazines, you kind of know that there is a whole team behind creating those amazing images and you know that’s not reality, but I think where social media is so dangerous is that they portray it as reality.”

“I personally still don’t agree with photoshopping or editing in fitness magazines, but at least you know that it is really a performance, whereas social media is designed,” said Amy, who stopped using Instagram after she found it to be an incredibly toxic environment. “It is still a performance, but it’s dressed up as real life and so, the people who look amazing and have all of these great photos of them doing workouts, a lot has gone into making that happen and it is essentially a job because they spend so much time doing it.”

It would be incredibly naïve to say that there weren’t enormous money-making opportunities to be made by looking good on social media and telling others this is how you look as good as me

Matt Evans, health and fitness journalist

In-demand fitness influencers can make hundreds of pounds for a single post, according to research by Curry’s and the Influencer Marketing centre. With almost 4 million followers, British fitness influencer Joe Wicks can earn up to £10,500 for each Instagram post he makes, just by sharing workout advice and nutritional diet plans.

Maintaining and expanding a loyal following is essential for people whose full-time job is to create content for social media. While some fitness influencers may have the best interests of their followers at heart, according to health and fitness journalist Matt Evans, ultimately what drives these influencers to be successful on social media is the opportunity to make money.

“I think some fitness influencers have their followers’ best interests at heart, but It would be incredibly naïve to say that there weren’t enormous money-making opportunities to be made by looking good on social media and telling others this is how you look as good as me,” said Matt. “Whether it is sponsored content or selling supplements or clothing, there are enormous money-making opportunities, so anyone in this day and age with a six pack and an iPhone I’m sure has been tempted to jump on Instagram and make a quick buck.”

Social media influencers are subject to very few rules when it comes to sponsorship deals and unlike fitness magazines, they can promote what they like without any evidence that the product they are advertising actually works or that they use it themselves.

Michelle Lewin has more than 15 million Instagram followers who pay attention to her meal prep, exercise advice and gym selfies. She was, however, widely criticised in 2018 for encouraging poor dietary habits as well as for endorsing extremely dangerous weight loss pills.

It may be quite detrimental for consumers to seek advice from social media influencers who lack credentials or understanding of the products they are advertising. Matt said, “When people follow these workouts and they don’t see the results they see on their phone, it can lead them to trying increasingly dangerous stuff whether its crash dieting, negative body image issues, low self-esteem, anxiety and depression.”

People are using social media more than ever to get free workouts, nutrition advice, and wellness support, which is fuelling the success of fitness influencers in the industry, according to a Cleveland Clinic and Parade Magazine survey. More than half of the women surveyed between the ages of 25 and 49 have made health or fitness decisions after visiting social media.

With the rapid growth of fitness influencers, many people have questioned whether they truly want to help their followers achieve a healthier lifestyle or if they are using their platform for personal gain. Fitness influencer Brittany Dawn Davis endured severe backlash from her followers in 2018 when she scammed them into paying for personalised diet plans, workout regimens, and online coaching sessions only to deliver nothing. Instead, her followers received a generic diet and workout plan that weren’t unique to them.

Davis sold custom fitness plans ranging from $92 to $300, as well as her own personal time to each client, but after conversing with one another, clients realised they were given similar or identical plans and never had face-to-face interaction with the fitness coach.

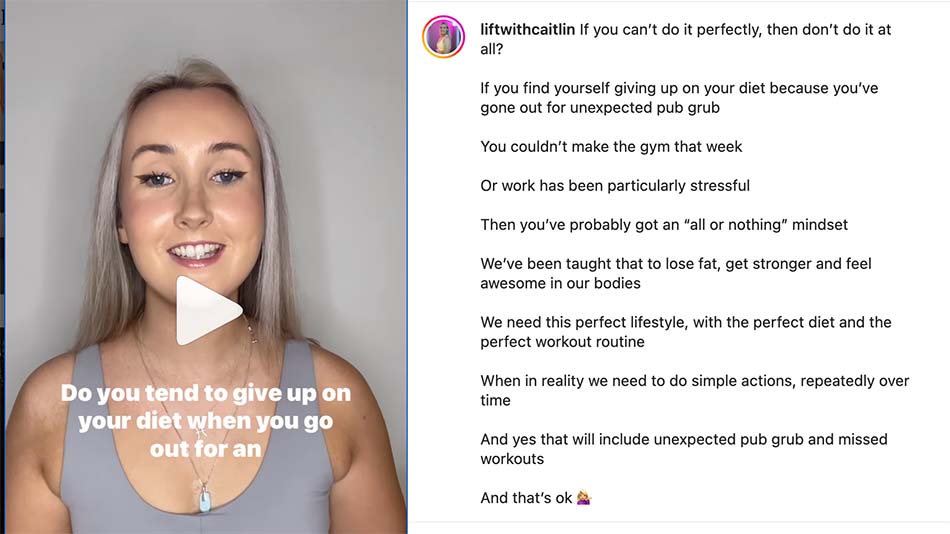

While some fitness influencers have genuine intentions and aim to positively impact their followers’ lives, according to personal trainer Caitlin Davies, there are still many on social media who prioritise making money over the well-being of their followers, demolishing the reputation of those trying to do good.

“It is easy to just make up or exaggerate the truth and do anything to get the reach, and then as soon as you get the reach, people will start buying a programme, so it can be really abused,” said Caitlin Davies, who initially launched her fitness account on Instagram for herself while she began her PT training course.

Now that she has a strong following, Caitlin recognises how easy it is for fitness influencers to take advantage of their consumers and use them for their own benefit, putting their needs before their follower’s welfare. “You could earn money if you wanted to and get that following, showing what you do and then as soon as you have that following you could totally take advantage of it and sell them something that has no value at all, and if your morals are ok with that, you’d earn loads of money.”

The reputation of online coaching is being tainted by people who are leveraging their status to get more possibilities, according to Caitlin, who has witnessed first-hand the harm other fitness influencers have done to their consumers. She said, “potential clients have had a bad experience in the past because they got sent a PDF of what to eat and told to go to the gym a couple of times a week, and that’s what they expect online coaching is and the rest of us have to re-teach them and try and get them to trust us.”

You actually stand out more in fitness now if you look normal than if you are absolutely ripped

Caitlin Davies, Fitness Influencer and Personal Trainer

Following the advice of fitness influencers who normalise various body types is becoming more popular. It’s important to have a good working connection with your personal trainer, says Caitlin, who thinks you shouldn’t follow fitness influencers just because of how they look but rather because of how they can help you achieve your own ambitions.

Since starting her fitness account, Caitlin has suggested that one way for fitness influencers to appear more authentic is to be more approachable with their followers by demonstrating to them that they also lead ordinary lives. “Looking normal and relatable, that actually appeals to them, so I think you suddenly learn that it is a big benefit and part of your brand, that you are a normal person,” she said. “You actually stand out more in fitness now if you look normal than if you are absolutely ripped.”