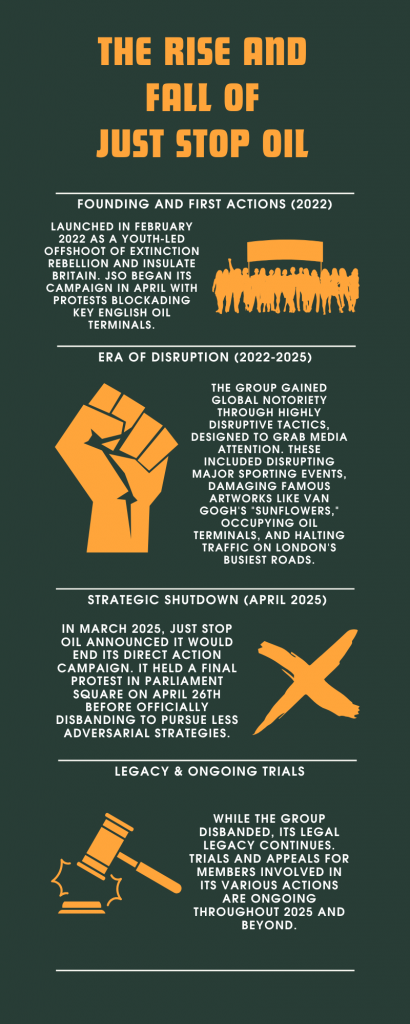

In April 2025, the UK’s loudest climate movement vanished overnight. Some say Just Stop Oil was ‘policed to extinction’, its members say they won. But what really caused their shutdown?

It was still dark when the raid hit.

On a leafy South London street, riot police smashed through the front door of a semi-detached house. Equipped in helmets, batons, and body armour. Their heavy boots thundering across the wooden floor.

“Hands visible! Stay where you are!”

Inside, activists were yanked from sleeping bags and sofas. Phones, books, and bags were photographed, drawers were emptied, luminous-orange banners unfurled.

James Skeet – barefoot, groggy, cuffed – was dragged into the garden without a word of explanation. “They sent 50 riot cops to burst my door open,” Skeet recalls. “A whole street’s worth. It was crazy.”

He hadn’t committed a crime. Not yet. James Skeet, a seasoned Just Stop Oil activist on his way to an interview with Piers Morgan, was arrested for staying in a house where others had allegedly planned a protest, an M25 blockade that never happened.

Scenes like this have led some to claim Just Stop Oil was policed to extinction. Infiltration. Surveillance. Raids. Prosecutions. The legal walls closed in, and activists ran out of breathing room. Eventually, the movement collapsed.

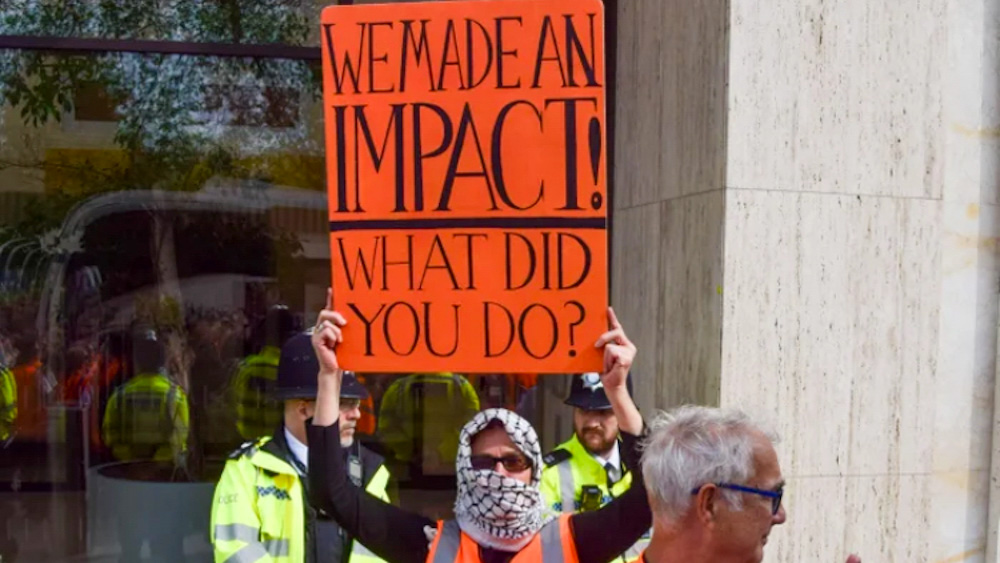

But Just Stop Oil rejects that idea.

In its final press release, the group was clear on its stance:

“Just Stop Oil’s initial demand to end new oil and gas is now government policy, making us one of the most successful civil resistance campaigns in recent history.” As they told supporters, “it is the end of soup on Van Goghs, cornstarch on Stonehenge and slow marching in the streets.”

According to James Skeet, the end of Britain’s most infamous modern political group was largely anticlimactic, “It wasn’t a big celebratory thing,” he says. “it was like: oh. We won. All right. What now?”

Anna Holland was one of two young people who threw Heinz tomato soup on Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ painting – one of the most infamous climate protest stunts in recent years. Holland, believes the organisation should’ve ended even earlier, saving itself from “petering out,” by declaring victory with the introduction of a new Labour Government: “Just Stop Oil probably should have shut down when Labour came into power, because Labour came into power with the decision to end all new oil and gas licences. That was our demand met. That was our victory. At that point, we should have shut down, because that’s what we set out to do.”

“With social movements, especially in recent decades, it is so rare that we get wins. We don’t know how to celebrate them when we do.”

A Movement Designed To End

For Skeet and others in the core group, the shutdown wasn’t a retreat. It was a designed exit. The Just Stop Oil organisers realised the group would eventually lose their drive, deciding to shut down with a win, before the state could shut them down or the group fell into obscurity, “One thing you notice about the mechanics of social movements is they go in boom-and-bust cycles,” he says. “you get maybe three-year windows. After a while, you start to see the pattern.”

Just Stop Oil was never intended to last. It was built for a singular goal: to end new UK oil and gas licences. That narrow focus was a deliberate contrast to sprawling predecessors like Extinction Rebellion, or Fridays for Future. No assemblies. No manifesto. No internal strife over which causes to support. Just Stop Oil was structured. Activists volunteered for action, and a leadership team assigned them. The movement was a slick machine, built for efficiency. Designed for disruption – and to achieve their one demand.

And, at least in policy terms, they got it.

The new Labour Government ruled new oil and gas licences unlawful. But in doing so, it slashed taxes on oil companies operating in the North Sea. So, whilst JSO achieved its stated goal, North Sea oil drilling still gained ground. Ed Milliband, Labour’s Energy Secretary, framed the move as pragmatic. “Oil and gas production will continue to play an important role, and as the world embraces the drive to clean energy, the North Sea can power our plan for change and a clean energy future in the decades ahead.”

Other leftist voices condemned the movement’s victory. GMB Union, an industrial trade union representing over 600,000 UK workers, advocated against the policy of ending new licenses. Speaking to the BBC, its General Secretary Gary Smith cited concerns around global instability. “In the new geopolitical reality – it’s madness. If the North Sea is being prematurely closed down and we are increasing import dependence – that’s bad for jobs, economic growth and national security.”

Just Stop Oil outwardly ignored the criticism, celebrating the win they were given. They said, “We’ve kept over 4.4 billion barrels of oil in the ground and the courts have ruled new oil and gas licenses unlawful,” JSO’s shutdown press release stated, “we exposed the corruption at the heart of our legal system… And we will continue to speak out for our political prisoners.”

Still, inside the movement, no one thinks the crisis is solved, or that the fight for the climate is over.

“Collapse is basically baked in,” Skeet says. “we’re talking food riots, we’re talking full societal collapse potentially. We’re going to be dealing with some serious shit, mark my words.”

Roger Hallam, JSO’s most visible founder, now serving prison time for his role in the group’s M25 gantry protests, offered a darker assessment. Speaking to the BBC from his cell, Hallam admitted the fight was far from won, saying in the grand scale of the crisis, the group had only made a “marginal impact” on the climate emergency. That failure, he claimed, lay not with Just Stop Oil’s activists, but with the “elites and our leaders” who had “walked away from their responsibility to tackle the climate crisis.”

The State Strikes Back

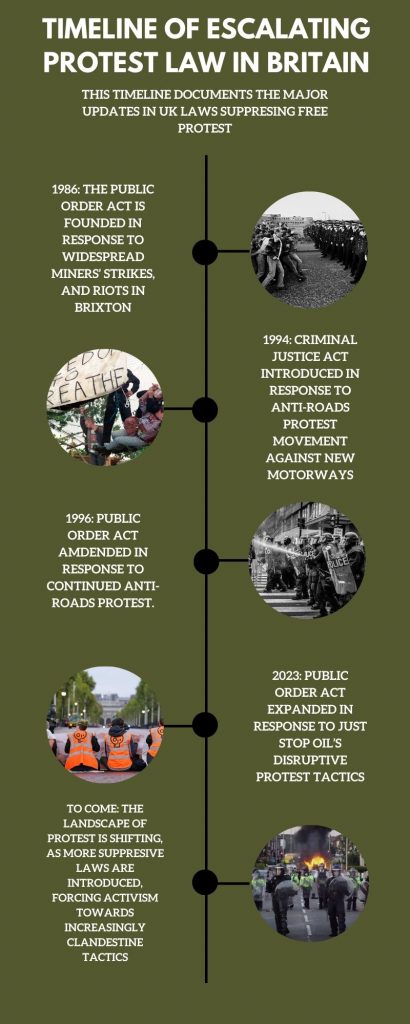

While JSO racked up headlines, the state fought back – hard, condemning activists in an unprecedented state suppression campaign. In three years, Britain passed sweeping new public order laws, many drafted with input from oil-linked think tanks. Blocking roads, ‘locking-on’, even making sufficient noise at protests – all became criminal offences.

The tipping point came with the Stansted 15 ruling, which gutted the necessity defence—the legal argument that a crime was justified to prevent greater harm. “The legal space for protest shrank dramatically,” says Professor Graeme Hayes, a protest law expert at Aston University. “Activists now face jail time without being able to explain why they acted. That’s changed everything. It’s fundamentally anti-democratic. It denies activists their speech rights in court. But it also denies juries their decisional function. It enables state overreach and removes a valuable feedback mechanism.”

Hayes criticises the policies implemented by current Secretary of State, Yvette Cooper. “I don’t think they care,” he says, “Yvette Cooper for example simply doesn’t care if activists can’t justify themselves.”

James Skeet knows it first-hand, having been drawn through a multi-year court case for his pre-emptive arrest in an alleged conspiracy to stage a gantry protest. “I’ve just come out of a court case where I was looking at four to five years,” he says. “the consequences are massive.”

Holland has also seen the effects of state suppression. Released on conditional discharge, all signs pointed to them being able to avoid time behind bars. “I had glowing character references, I’m part-way through a master’s degree, and I’m under 25, all signs pointed to me getting suspended at worst. And then…” she pauses for a moment, “I was sent to prison anyway, and still got one of the harshest sentences for criminal damage ever, and that was a really hard moment. I had essentially gone against my nature for the past two years, and not taken any action, all to protect my family. And then I couldn’t protect them.”

Holland admits that state suppression was successful. The government’s campaign of arrests, imprisonment, and imposing bail conditions meant there simply weren’t enough willing activists for the movement to continue. “The policing was definitely a big part of it. Up until the Air Force actions, when so many of us got sent to prison in essentially one fell swoop, it was pretty much the same few people who were working full-time within Just Stop Oil. There was a small group, because it’d gotten so difficult to get people to stand up and join us, so there was simply no one to take our place when we all went to prison.”

Privilege And The Price Of Disruption

But even within the movement, there was a quiet reckoning: JSO’s tactics relied on privilege.

The average member? White. Middle class. University educated. The kind of person who could risk arrest without risking everything.

“If you’re going to encourage people to get arrested, class privilege is an asset,” says Professor Hayes. “it’s a form of white privilege… the environmental movement remains very white, very middle class.”

Those within the movement argue that their lack of diversity is exactly the point, allowing activists to be arrested en-masse, a form of protest in of itself. “With regards to us being predominantly white and middle class. Yeah, that’s absolutely fair. We are. The way our legal system is rigged in this country, it’s white middle-class people who are most able to get arrested and take these actions that break the law.”

“The police are so systemically racist. As a non-binary person myself, even as a female-bodied person, I was terrified about how the police would treat me and their prejudice against me. Of course, you’re going to see white middle class people on these front lines, because we are the people who can give up the time and give up the money to be able to take these actions.”

Still, they reckon with the criticism, taking it in their stride.

“I almost sometimes feel quite vindicated when people use these arguments against us… If it’s the upper class trying to punch down at us, it makes me feel quite vindicated to think about the only thing they can find to criticise about us is who it is taking the action.”

What Comes Next?

“Governments everywhere are retreating from doing what is needed,” Just Stop Oil’s final message warned. “as we head towards 2°C of global heating by the 2030s… Billions of people will have to move or die.”

Their tone wasn’t triumphant. It was urgent.

“We are creating a new strategy… Nothing short of a revolution is going to protect us from the coming storms.”

Whether that strategy means smaller cells, a pivot to political systems, or something more radical, no one’s saying. Yet.

But one thing is clear: the next phase won’t look like the last.

“It’s not going to be about disruption anymore,” Skeet says. “not in the same way. Not at the same scale.”

Holland sees the prescription of Palestine Action as a watershed moment for protest in Britain. The state’s move to proscribe the group has been largely unpopular, fuelling the existing pro-Palestine movement: “Whatever comes next, it’s going to be different. And I think this has been the turning point we’ve needed… It feels like the first time the public are really standing behind us and are really on our side.”

They’re already thinking beyond protest, towards organising politically, “What I want to see happen is a joining together of community focus groups and more disruptive radical groups… When we bring down this system of corruption and genocide and sheer injustice on all fronts, we need to make sure that we have the foundations ready to build the community we want to see.”

And for all the scrutiny, for all the collapse and the chaos, Holland remains resolute: “History will vindicate us. This is something we see happen in every social movement. Whatever movement is fighting for good, they are hated at the time and then they are loved.”