According to a recent report, the UK needs to invest more effort in learning Chinese culture and language. What are the obstacles to developing Mandarin and Chinese Studies in the UK, and what is the power of learning Chinese for individuals and also for promoting UK-China relations?

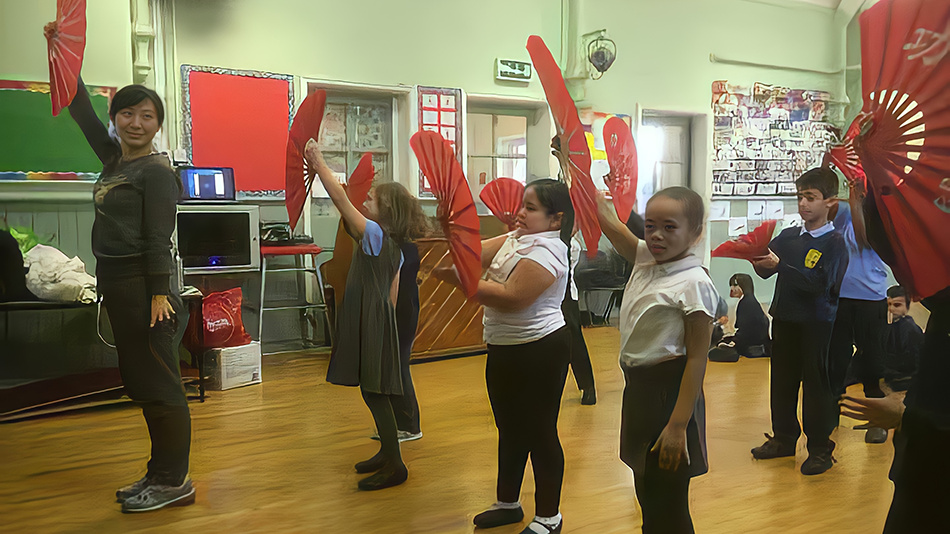

Lucy gently wrote the last stroke on the paper with a brush, swiped it upwards, then exhaled softly. Two large Chinese characters “Ni hao” stood out on the paper.

“What does it mean?” she asked.

“It means Hello,” replied Mandarin teacher Liu Jing, who then read them slowly in Chinese.

As 11-year-old Lucy followed the pronunciation and successfully read it out, Liu gave her big applause and congratulated her on a good start to her Chinese learning journey.

Lucy immediately lit up with a smile and said, “Oh, it’s amazing!” “Ni hao! Ni hao! Ni hao…” She kept repeating this phrase in her newly unlocked language.

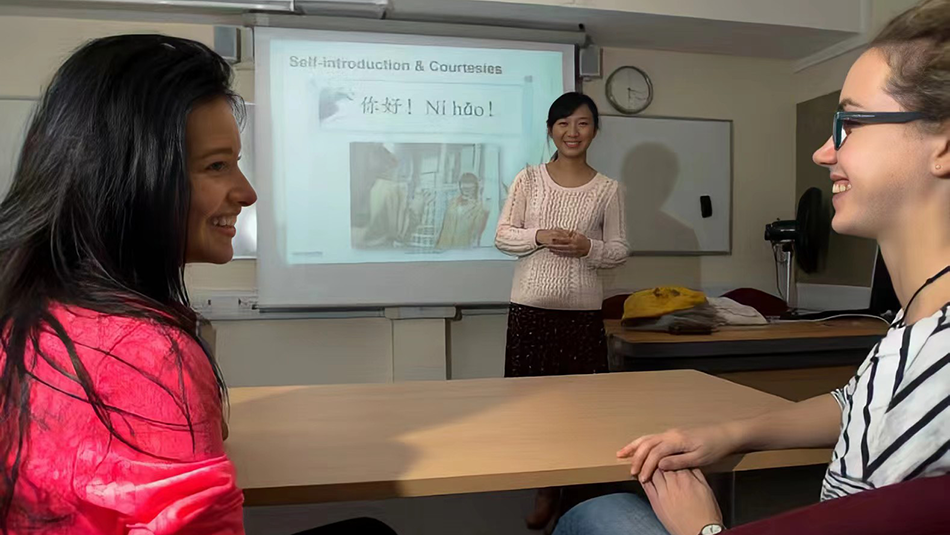

It was the Mandarin lesson in the Chepstow School, as a part of the “Confucius Classroom” program for secondary school students to learn Chinese in Cardiff. Having taught Mandarin in the UK for eight years, Liu deeply realized how learning Chinese could change British people’s careers.

She finds that many of her British students who are proficient in Mandarin tend to gain a greater competitive advantage and have more employment options in the workplace.

“As more and more Chinese go to the workplace in the UK, learning Chinese has far-reaching implications for the younger generation in the UK, as they need to work with Chinese colleagues in the future,” says Liu, now a Chinese tutor in the School of Modern Language at Cardiff University.

As more and more Chinese go to the workplace in the UK, learning Chinese has far-reaching implications for the younger generation in the UK, as they need to work with Chinese colleagues in the future.

Liu Jing, now a Chinese tutor in the School of Modern Language at Cardiff University

Liu’s opinion coincides with the growing popularity of learning Chinese in the UK these years. According to Financial Times, an increasing number of people in the UK are starting to take an interest in learning Mandarin. Research released by British Council also finds that UK parents see Mandarin Chinese as the ‘most beneficial’ non-European language for their children to learn, and a growing number of students take up the language in schools across the UK.

It’s not just China’s significance on a global scale that makes Mandarin an appealing alternative to learning a European language for British people. Many teenagers believe it enables them to explore a brand-new culture and develop a different worldview, and some students who majored in Chinese were particularly resonated.

“Becoming involved with Chinese language and culture was a personal interest because of the history and arts as well as my awareness of China’s significance on a global scale.” says Kelsey Mckue, an undergraduate student in Modern Chinese at Cardiff University, “I am pretty much interested in Chinese New Year customs and admire the beauty of calligraphy.”

However, a recent report by the Higher Education Policy Institute(Hepi) shows concern over the development of Chinese education in the UK education system. It suggests that the UK education system is facing “a severe national deficit” in China literacy and Mandarin speakers as the number of Chinese Studies students has not increased in the past 25 years.

Wang Xuan, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at Cardiff University, believes that the “deficit” is a lack of intercultural communication. “The number of Mandarin learners has increased, but there is still a shortage of Chinese Studies students to develop intercultural communication skills,” says she, “It’s a step further than learning mandarin.”

The Hepi report states that the UK can benefit more from cooperating with the Chinese government and companies if there are greater trust and more understanding of China, citing the government’s decision to remove Huawei from the UK network, which was estimated to cost BT £500m.

They don’t have enough talent who can do trade and political cooperation with China, many people in the government can only speak Mandarin but cannot understand and work with their Chinese counterparts.

Wang Xuan, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at Cardiff University

According to Wang, not many British universities offer degrees and courses for Chinese Studies, and the lack of teaching resources are important reasons why Chinese studies cannot develop in the UK.

“Many British universities have cut off many liberal arts majors, not to mention offer Chinese Studies degrees,” says Wang, “Funding for humanities majors has been shrinking, so universities don’t have enough money to hire professors in Chinese Studies.”

In British universities, however, some UK-China co-operative Chinese-language education projects have proved to be beneficial for the development of British students with intercultural communication skills. Cardiff University has partnered with Beijing Normal University to launch a dual degree program in Chinese Studies, which enables students to have a two-year immersive study experience in China.

As one of the initiators of the project, Wang mentions that these students have two years of study in China based on the real Chinese cultural, working, and learning environment, which could combine theory with practice and naturally cultivate intercultural communication skills.

Nick Ng, a third-year student of the program, visited China’s historical monuments and cultural sites during his first few months there, an experience he called the best start to his journey of learning Chinese. “Not only could I practice my admittedly rudimentary Chinese language skills in the places I visited, but I was also able to feel a true intimacy with the country and culture,” he says.

Apart from the immersive learning in China, Wang believes that studying Chinese in British schools can also help students develop a deep insight into its culture and society which is quite different from the West, and greatly expand their view of this diverse world.

“The education of today’s British youth should be based on a worldview of global citizenship,” she says, “Therefore, the British education system should include teaching different civilizations and cultures to students, and Chinese Studies is a typical one.”

Some students think that studying Chinese has changed their perceptions of China and brought them a different insight into China’s society and current affairs. Joe Davis, a fourth-year student of the program, shares his experiences of studying Chinese modern history, in which he was amazed at how much China has changed since its reform and opening up.

“Things up here in 1978. Chinese economy and lifestyle have improved massively. So that was an attractive part to study about China is why in recent history have had such amazing growth in their standard of living,” he says.

After exploring Chinese culture, Oliver Hassan, the program’s first-year student, thinks that he can now look at China-related news more comprehensively as he never takes it for granted that what BBC says is true and also looks at what Chinese media says.

“If an English journalist writes something about China, they mainly understand China from a Western political perspective, but not from a cultural perspective,” he says, “If you want to understand the case, the cultural aspect is incredibly important. And that is what I have gained from taking my degree.”

Wang thinks that the first step in improving British people’s intercultural communication skills in Chinese is to develop elementary Chinese education, as a preparatory stage for studying Chinese at university.

“Many students proficient in Chinese start at primary school level and continue through middle and high school, thus giving them a good foundation in Chinese, and then it is not difficult to go deeper,” she said, adding that this makes them more likely to be Chinese studies students.

Wales has already put efforts into popularizing Mandarin and elementary Chinese among minors. Cardiff Confucius Institute has launched a school-based Chinese learning program “Confucius Classroom” which provides Mandarin and Chinese culture courses to 16 primary schools and secondary schools across Wales.

Meanwhile, according to Wang, the Chinese-themed seminar, cultural activities, and experiential classes for primary and secondary school students can also inspire students to choose Chinese studies when entering university. “We regularly visit primary and high schools in Wales and ask international students who have returned from China to share their experiences of studying abroad, which has been very well received by the students,” she says.

The growth of Chinese Studies and Mandarin speakers can play an important role in the UK strategy and policies for better relations with China, according to a report from King’s College of London. However, Wang thinks that the two nations’ relations are a topic far more complicated and unpredictable than language itself.

“The UK is a multi-party parliamentary system, so the future of its relationship with China greatly depends on which party and political leader take office. Besides, the international situation also plays a big role,” she explains.

Even so, Wang remains confident in a better prospect for UK-China relations. “As China’s global influence grows, the increase of British Mandarin speakers is an irreversible trend,” she said. “The weathervane turns that direction, so how soon can the boat reach that end depends on the bilateral relations between two nations in trade, education, and other areas.”

Today, Liu Jing is still dedicated to teaching Chinese languages and culture to the British. Apart from delivering Languages for All courses and Adult courses in the universities, she also plans to teach elementary Chinese to secondary school students in Cardiff next semester.

Rather than changing the stereotype of British learners about China, she hopes that her classes can help more and more British children to understand the country and love its culture.

“I want to open a window for the British to understand the real China and convey to them the positive side of China, not just what the western media conveys,” says Liu.

I want to open a window for the British to understand the real China and convey to them the positive side of China, not just what the western media conveys.

Liu Jing, a Chinese tutor in the School of Modern Language at Cardiff University