Covid-19 arrived at a time when western governments had seen a surge in populist politics. Leaders who did not want to be seen getting the jab told voters not to listen to experts. Were they responsible for the rise in the anti-vaxxer movement?

September 26, 2020 was cloudy above the crowds gathered at the Rose Garden in the White House. A world-renowned political ceremony was taking place here. After the death of the last US justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a new justice, Amy Coney Barrett, who was supported by the conservative party leader, was about to be introduced at this gathering.

Dignitaries and celebrities who attended the ceremony did not conform to social distancing rules during seating and few wore masks. They broke out in applause to this nominating of their leader, President Donald Trump. However, at least seven people who attended this event were later reported to have had the coronavirus, including the US president and his first lady.

The president had been quarantined, during which accepted nursing; he also had been reported to have gone to the hospital by helicopter due to worsening symptoms. While official reports insist his spirit was good, Trump himself said to the Washington Post: “I am going to Walter Reed hospital; I think I am doing good, but we just need to make sure that things work out.” He also addressed the public in a short video about the virus: “Don’t let it dominate your lives.”

However, inside the White House, a long-term atmosphere of invincibility toward viruses was turning into apprehension and panic. An outside adviser who worked for months in proximity, largely without masks, said to the Washington Post: “People are losing their minds. We don’t want to be talking about coronavirus [because of the] pandemic while now we’re talking about coronavirus. Trump can’t protect the country. He couldn’t even protect himself.”

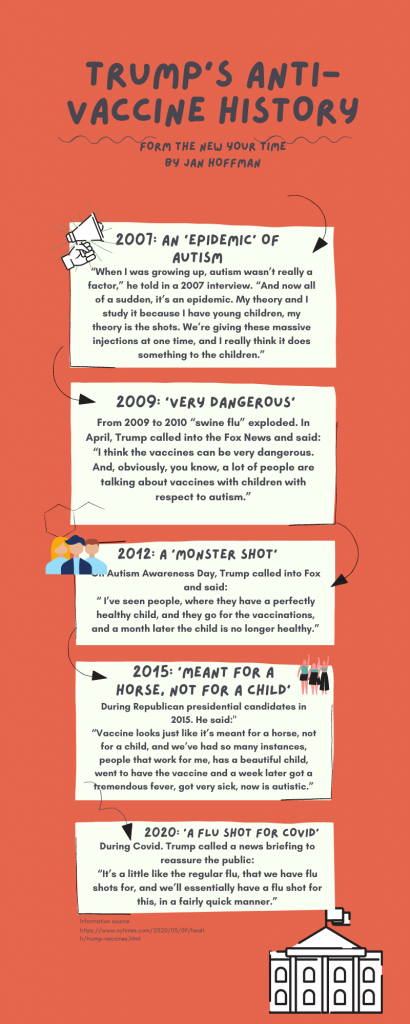

This kind of contradiction in Trump’s administrative team was not new and was representative of what would explode in the months to come. Not only did he and his team show a reckless attitude by avoiding serious talk of Covid, but also, according to the report in the New York Times, he had a long history of scepticism about medical treatment, especially regarding vaccines.

Josephine Lukito, media and politics researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, has pointed out that Trump’s attitude about public health care has had a profound effect not only on the US but also on the world. She said: “Trump’s team was disappointing. People can see the ripple effect in a lot of other countries due to his irresponsibility: this is a serious moment, it wasn’t just Americans looking at him, other world leaders were also turning to Trump and looking at how they should be taking care of their countries.”

Dr Lukito also worries about the impact of Trump’s political expression on the spread of the pandemic. In her view, his irresponsible behaviour and careless speech about vaccines had the potential to stimulate an anti-vaccine movement. In fact, she holds him responsible for the movement that did arise, although he himself denied it. Given his history of spreading misinformation, “it’s not surprising that he is bad for the Covid vaccine,” she said.

Research has confirmed that influential populist political leaders like Trump can fuel the anti-vaccine movement; conversely, anti-vaccine campaigns are not as severe in countries such as Portugal and Belgium, which have low support for populist leaders, as one report discovered. According to the BBC, populism separates two main groups of people: the “ordinary class” and “the corrupt elite,” to the effect that it encourages the public to decide for themselves, rather than take advice from the “elite class.” This parallels the stance of the anti-vaxxers. Unsurprisingly, supporters in these two groups also have a big overlap. The similarity between the rhetoric of populist leaders and that of the anti-vaxxers reflects their similar core values: both claim, “we’ve had enough experts.”

Dr Ceri Hughes, a researcher in politics and media at Cardiff University, elaborates on the core values promoted by populist leaders and the similarities between these values and those of the anti-vaccine movement. As he said, “Populist leaders make appeals to say they want common sense. They want the real people to make decisions rather than the elite class, which is a rugged individualism of freedom or freedom to choose. This is the same as anti-vaxxers because doctors, the medical establishment, [and] researchers at university all fall under this elite category.”

Dr Hughes has also said: “Populism brings a misinformation flood and makes the world into a misleading information manipulated age. In the US, whether to get a vaccination is becoming a political stance rather than a personal choice.”

In the West, Trump’s influence on the anti-vaccine movement is unquestionable. The New York Times revealed that Trump was dismissive of scientific authority for a full decade before he became president. Furthermore, he did not modify or retract any of his statements when physicians forcefully repudiated him. Rather, he let it be known that he is proud of never having got a flu vaccine. Despite the overwhelming evidence from the scientific community attesting to the efficacy and safety of vaccines, he continued to spread skepticism and outright distrust of vaccines on social media. His disparaging comments were targeted to a whole range of vaccines, from childhood immunizations, which he linked with autism, to a dismissal of the flu vaccine.

Due to the high death toll during the Covid pandemic, Trump had to adjust his anti-vaccine rhetoric to make room for an exception: a powerful vaccine for the public that he promised his team would provide. However, the production of this “super vaccine” was nowhere in the making, and the promise of its delivery was based not on expert forecasting but on his own judgment.

Politico’s research also indicates that after the Covid vaccines were produced, a paradox in attitude existed among Trump supporters, who regarded the speed of its production as Trump’s contribution, while also insisting that people should not get vaccinated unless they work in a high-risk environment. They did not think the government should tell them what they needed to do and remained skeptical of mass vaccination, viewing it as risky. As Emerald Robinson, White House correspondent for the pro-Trump television network Newsmax, said on Twitter: “People don’t need vaccines, but the politicians want it for control.”

This kind of populist medical opinion is satisfying psychologically because it allows people to feel in control of their own lives. Only they can decide what’s right for themselves. Unfortunately, the strategy is threatening people’s lives, as Dr. Hughes has stated. Anti-intellectualism, which along with elitism lies at the root of populism, “is where people are prepared to die rather than do what the government or anyone is telling them,” Dr. Hughes says. “They believe they are free people; they can decide by themselves.”

Modern technology enables this stance. As Dr. Hughes also points out, formerly, “people had to rely on doctors to know what was wrong with them when they felt ill . . . while now people can Google it and diagnose themselves in five minutes. And that’s easier to diagnose in the way that they want. So, the intelligence divergence and anti-intellectualism movement have increased.”

The easy availability of technology supports populism and anti-intellectualism in another way: it allows populist leaders to use misleading content to manipulate political election directions. For example, during the US election in 2020, Trump’s administration was fired, and Biden won the presidential position. The BBC confirmed the reasons for Trump’s failure: chaotic managing and controlling of the Covid pandemic along with his unfounded conspiracy theory threats. Ironically, Trump utilized misleading information in an attempt to win the election; that he failed was a rare triumph of reason.

Trump did not accept his failure all at once. He published a speech to attack Biden’s team and attributed the result to fabricated cheating. In his words, “Joe Biden kept talking about how good [a] job he’s doing on the distribution of the vaccine that was developed by the Trump administration. He’s not doing well at all. People are refusing to take the vaccine because they don’t trust his administration, they don’t trust the election results.” CNN criticized this segment of his remarks about the Covid-vaccine as being highly misleading to the public. In sum, Trump affirmed misguided doubts people have about receiving the Covid-19 vaccine, while painting the vaccine push in a partisan light with his comparison to the 2020 election.

According to Dr Lukito, misleading public statements by influential political leaders can have a huge impact on public attitudes to healthcare. As she said, “If there are prominent politicians or influential individuals who spread misinformation, especially in the medical field, it will increase the likelihood that other people consume this kind of misinformation.”

Dr Hughes shows that misinformation lay at the foundation of Trump’s campaign. As he pointed out, “the Washington Post fact-checker listed 30,000 times where Trump said something untrue. During his presidency [this kind of lying] became normalized.”

In the UK, although populism is not the mainstream ideology of the British party, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been seen as a fervent supporter of Trump. He also is famous for losing facts. Thus, his triumph in Brexit has been seen as resonant with Trump’s political success in the US. For example, on the issue of Brexit immigration, the campaign, represented by him, has spread many conspiracy theories to galvanize supporters’ emotions.

Dr Hughes believes this kind of fearmongering is occurring more frequently than ever among populist leaders. What would once have been heavily sanctioned, “now seems to be accepted,” he said. He is referring to the spins on truth that amount to outright lies.

The anti-vaccine movement has been foundational to Donald Trump’s support. One survey conducted in 2018 by Dr Matthew Hornsey and his colleagues confirms that Trump’s voters are more vaccine-hesitant than other Americans. His research also shows that if someone believes any aspect of one kind of conspiracy theory, that person is more likely to have a conspiracy theory worldview.

In addition to advancing conspiracy theories, Trump has been seen as the hero of other kinds of anti-intellectual movements, such as Qanon. This movement is inextricably linked to the anti-vaccine protests in that are all based on conspiracy theories having their origin in the belief that President Trump is waging a secret war against the so-called “elite.” These are the “Satan-worshipping pedophiles” in government, business, and the media. Although Trump never supported Qanon directly, his frequent interactions with the leaders of the movement, which is riddled with internal controversy, are indicative of his underlying support.

According to Dr Hughes, anti-intellectualism and anti-elitism are currently being used to advantage more than ever among the political leaders of populist campaigns. As he said, “these political leaders present information in a manner they must know is going to be appealing to a certain group of the populace. False information is more appealing to people.”

It follows that false information is what populist leaders disseminate to the public. The resulting political schisms need to be taken with the utmost seriousness by society. Although some people are trying to bridge the increasing gulf between political ideologies, this will not happen anytime soon when others, when discussing the pandemic and vaccines, are more concerned with their political stance and identity than with real lives.

This is the view of Dr. Hughes, he said : Extreme political polarization, especially in the US, but also between parties in the UK and other western countries, has gone one for many years. Our issue isn’t largely resolved and there’s lots of residual resentment. And that’s going to take time to heal.