The number of adolescents diagnosed as bipolar disorder in China has gone up significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to psychiatrists. How has the pandemic contributed to the rising figure of young patients?

Fang Suyi clenched the book tightly in her hand, her brows furrowed, and stumblingly spit out English words from her mouth. She had been sitting at her desk for an hour but had barely recited one-third of the text.

Recalling the terrible experience these days stuck at home due to seemingly endless days of lockdown in Shanghai since April, Fang’s mind suddenly went blank, her eyes went dark in a trance, and she slumped onto the table. “I quit!” Fang cried. Having struggled for two weeks, she could no longer bear it. With that, she pushed aside the clutter of books and papers on the table, rushed back to her room, and lay down.

From then on, leaving her bed seemed to be the most difficult thing for her. She locked herself in the room, cut off all contact with teachers, and swiped aimlessly at her phone all day.

“I realized that I was depressed. My bipolar disorder had returned,” says Fang Suyi, a 16-year-old high school girl who has suffered from bipolar disorder since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020.

I lost interest and motivation in anything, laying on bed and dwelling on painful things in my mind endlessly every day.

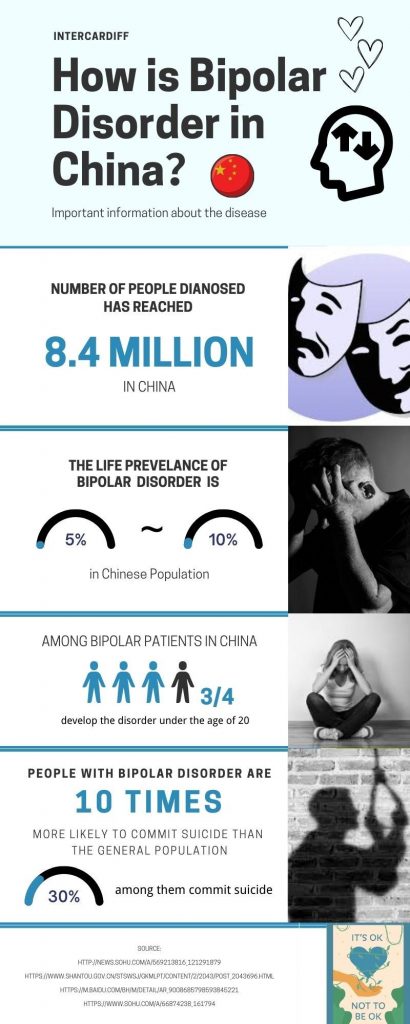

Fang is one among 8.4 million people in China who suffer from bipolar disorder, a psychological disorder characterized by both manic and depressive episodes, with “mood instability” that causes a radical shift in mood between extremely high(mania) and extremely low(depression).

Diagnosed with bipolar disorder at such a young age like Fang is not uncommon in Chinese society. According to Professor Xin Yu from the Institute of Mental Health, Peking University, the peak age of bipolar disorder’s onset in China is 15-19 years old. About three-fourths of patients develop the disorder before the age of 20, and about 50% of patients develop it around the age of 15.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend intensified. The number of people under the age of 17 diagnosed with bipolar disorder has risen significantly in the past three years, according to Nianhong Guan, a member of the Psychiatry Branch of Guangdong Medical Association.

Adolescents with bipolar disorder are at high risk of deliberate self-harm (DSH) and suicide, according to the Journal of Affective Disorders. Peng Daihui, a psychiatrist from Shanghai Mental Health Center, says the sharp rise in the number of young bipolar patients during the pandemic could lead to more adolescent patients resorting to extreme behaviors such as self-harm and suicide, “When they are in a depressive episode, extreme feelings of hopelessness may lead to extreme thoughts of misanthropy or even suicide. And during the over-excited manic episode, they may have extreme thoughts or acts like self-harm or violence to calm them down.”

Bingxuan Li, 15, from Hebei province went through both episodes during the pandemic and committed the different extreme behaviors mentioned by Peng. The 15-year-old junior high school girl swallowed an entire box of psychotropic drugs during a depressive episode when she dropped out of school because she despaired of her study and life, and it caused her food poisoning. But eventually, she was cured.

“The manic and depressive moods alternated twice a week. I was torn and suffered all the time, unable to think properly, and prone to harm myself,” Li recalls, showing her arms and thighs, which bore the scars she had cut with an art knife during her nervous breakdown when her mental state turned manic.

“They gave me temporary relief,” she adds.

What are the reasons behind the rapid increase in adolescent bipolar patients during the pandemic? Andrea Wu, the manager of Bipolar World, China’s first organization focusing on and speaking for bipolar disorder, believes that the increasing number of young people being accurately diagnosed with bipolar disorder contributes to this trend.

For many years, misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder has been common in China. A national study on bipolar disorder shows that the initial diagnosis accuracy is only 7.6%, with most being misdiagnosed as depression or schizophrenia.

However, the rate of misdiagnosis in young people has been declining in recent years, especially during the pandemic. Andrea attributed this to the growing awareness of bipolar disorder in the Chinese medical field. Doctors are thereby putting more emphasis on the alternating nature of depression and mania in bipolar disorder in the diagnostic period.

“In the past, when a patient told their doctor about their depressive symptoms, most doctors would just assume the patient had depression. But now doctors have realized that even if you only tell me about depression, they will still ask if you have times when your mood is high,” says Andrea, adding that more people with underlying symptoms of bipolar disorder are correctly diagnosed.

Despite the improved diagnosis accuracy, the number of adolescents who developed bipolar disorder or whose symptoms relapsed during the pandemic has also increased. Andrea argues that the prolonged isolation of adolescents at home because of the pandemic is another major cause.

“During the pandemic students have been at home in online classes, staying in a closed, monotonous environment, which for some hurts their mental state,” says Andrea. “In addition, because of the screen, even if someone is not well, it is not as easy to detect as when they are face to face, making it difficult to provide timely medical and psychological intervention.”

Since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, Chinese students have experienced multiple rounds of prolonged isolation at home, such as the 84-day citywide lockdown in Shanghai this year, during which students are barred from leaving home and neighborhood, and returning to school during the quarantine period, but took online courses instead.

Fang is among those who were locked at home taking online courses during the 84-day citywide lockdown. In late March, she was told she could not return to school and would have to take online classes from home. Her life had been disrupted since then. Cutting off from school life and losing contact with her classmates and teachers offline, her depression was growing, and she gradually lost interest in her study and daily routines.

“The anxiety and loneliness quickly intensified in the following weeks as I was overwhelmed by loads of study pressure with no one to talk to and no campus activities to engage in,” Fang says, adding that it was this lack of emotional outlet and accumulation of stress that brought her back to the depressive period leading to her inability to study.

The Chinese government has developed several ongoing mental health policies across the country in response to the mental health crisis due to the pandemic lockdown. And for adolescents, the Ministry of Education required psychiatrists and psychologists in the education system to open psychological support hotlines and online counseling services and provide online psychological crisis intervention services for primary and middle school students.

In spite of this, the situation that China has long faced with extremely low utilization of mental health services was particularly evident during the pandemic. According to a 2020 study on mental health assistance in China, only 4~6% of the general population actively sought out mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Andrea believes that China is at a disadvantage compared to many Western countries in terms of mental health interventions and treatment. “Foreign students have higher health insurance reimbursement for mental disorders,” Andrea explains, “Besides, schools in developed countries are equipped with more medical resources for psychological counseling and offer more sophisticated psychological assistance systems.”

Some psychiatrists believe that the heavy academic pressure during the pandemic has undoubtedly exacerbated middle school students’ mental health problems. Dr. Guo Li from Harbin, says that stressful events often trigger the onset of bipolar disorder, which can be a high-stress event related to study, work, or personal life.

For Fang, it was during her first year in senior high school, the most stressful period for Chinese students, that her depressive symptoms appeared. She recalls the month following the onset of her symptoms when she almost quit her study and drown in misery, “I was absent-mindedly attending online classes and shirked all the homework. My parents came to my room many times to persuade me to study, but I could do nothing but cry.”

However, the current situation that high school students are burdened with heavy study pressure is a long-term situation that remains during the pandemic period. Chinese students traditionally face national selection processes to get into high school and university respectively, which have been carried over in the three years following the COVID-19 outbreak. Students under lockdown still face intense study pressure as they have to prepare for the high school and university entrance exams.

Will things change? Andrea believes that it is difficult to improve teenagers’ mental health problems by relieving academic pressure at present. “It lies in the fact that China’s development level is not high enough and the country has a huge population. Such intense competition will always exist, and even the government can hardly solve the problem from the root,” She explains.

Having met many young patients not receiving adequate treatment due to busy school schedules, she sighed, and shook her head, “Not to discourage bipolar students and try to grant holidays to allow children for treatment, which is the best thing they can do at this stage.”

Fang’s situation, however, was reversed at the height of her depression.

One day she came across an excellent artwork from an art student, and an idea suddenly sprung into her mind—become an art student. “I was suddenly thinking that if I didn’t try to make the life choice of taking art exams now, I might have a very slim chance later on,” she says.

Fang realized that she needed to pull herself together and continue her studies to be admitted to art school and pursue a career path in painting.

“That was like a silver lining in the darkness,” she says. Feeling as if the long-lost hope could be perceived again, she began to pick up the study she had fallen behind. Between then and the recent days when she managed to take her final exams, her mental state tended to improve.

Discovering interests and building self-confidence are key to moving on from the depressive symptoms of bipolar disorder, according to Andrea after long contact with many bipolar patients who have recovered. “The onset of depression is itself a lack of interest and meaning for life. Finding interest and hope is like finding a breach of the illness on a spiritual level and then, together with medication, patients are more likely to recover from their symptoms,” she says.

This is true for Fang. With the lifting of the lockdown in Shanghai since June, her spirits have been improving, as has the city’s rejuvenation. She “unblocked” herself from the room and resumed meeting up with her friends offline. Now she is 100 percent sure that she will be back on campus next term.

While sticking to her medication and studies, she is also refining her painting skill. “For my career plan, being admitted to the China Academy of Art is the first step of my artistic dream. As long as I maintain a good attitude towards life as I continue to recover from my illness, I have confidence in this goal,” Fang says.