As more young women enter embalming, their videos challenge gender bias in China’s deathcare. Can a make-up brush on Douyin change minds?

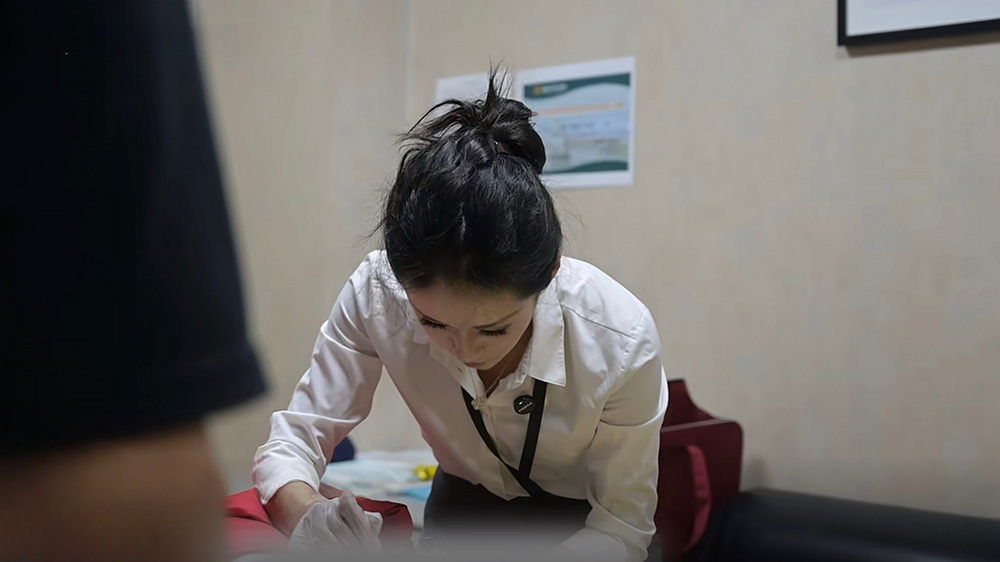

In each of her Douyin videos, Pan Honglei’s voice comes first—warm, steady, and addressed to the family just off camera. The frame often fades up from black, touches her face for a beat, then drops to gloves, tools, and a laid-out tray. No soundtrack or filters—just an orderly rhythm.

Her clips foreground method over mood: a fixed camera, gloved hands and tools in close-up, step labels on screen, and clear notes about what will not be shown. The point is simple: show the steps, keep the dignity.

“My friends always say that it’s a pity that you are so beautiful to do this job,” she said. “But what I want to say is, why does society have to divide occupation and gender? What men can do is the same as what women can do, and they can do better.”

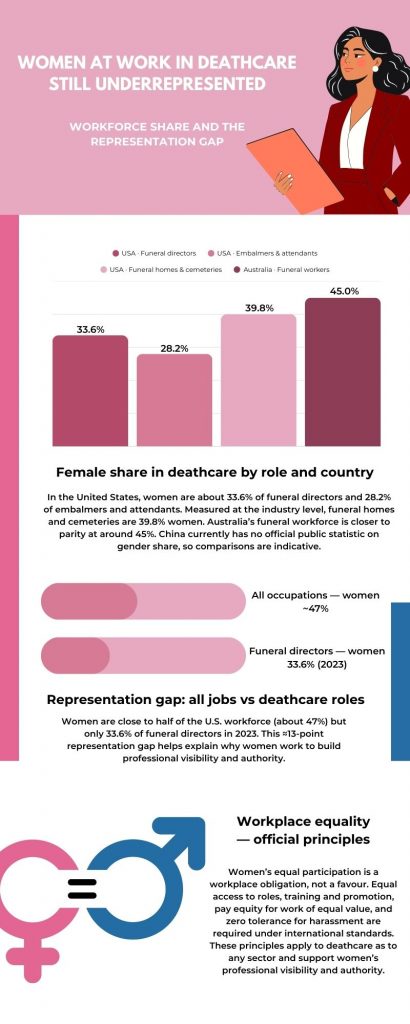

Although more women are entering funeral work worldwide, the balance remains uneven. U.S. occupational data indicate women are roughly one-third of morticians, undertakers, and funeral directors in 2023, a reminder the field still skews male.

In China, there are no official figures, and women publicly showing procedures on camera remain rare. Pan’s clips lay out steps while signalling standards and ethics at each stage, making the work legible and professional. For Pan, posting is about procedure rather than presence. Her calm, direct style helps audiences understand the craft itself.

On camera, women build authority by choices of tone and boundary: they lead with calm second-person explanations, “what the family will see next,” label each stage with plain terms, and state non-negotiables, such as “no faces, no IDs, no wounds.” In comments, they pin a short rule and answer recurring questions with factual micro-explainers. Over time, this teaching voice, rather than emotional framing, carries professional weight.

Authority is also built in word choice. Many women standardise terms in captions, using neutral “decedent/逝者” instead of harsher nouns, “family/家属” rather than informal kinship labels, and “restoration/修复” rather than “covering up/遮盖.” They avoid diminutives and slang. When addressing families, they switch to the second person, “what you’ll see next” and “how we keep consent,” to keep the room steady. Over time, this controlled vocabulary moves from captions into comments and Q&As. It gives viewers a shared set of terms and frames the work as care and craft, not spectacle.

Beyond the edit, authority is written in small on-screen choices. Many women keep a short caption template that repeats across clips: “what happens next,” “what we will not show,” and “what the family can expect.” The aim is to steady the room and set expectations before emotions take over. Several creators also publish a one-screen glossary that lists “restoration,” “camouflage,” and “suture line,” so viewers share the same words and stop calling repair work “covering up.” Over time, this vocabulary does quiet work. It lets an unfamiliar craft be discussed in public without drama.

The comments then act like a corridor class. Nursing students ask whether bruising can be softened; trainees want to know where stitches are tucked; a cousin asks what to wear to a wake. Replies are short and neutral, often pointing to the next clip, restating a no-faces/no-identifiers rule, and directing families to the funeral home for decisions. The tone is not influencer-style engagement but small, repeatable teaching. That style also sets a boundary: women don’t need to show more to prove competence; they need to keep the family’s consent and the craft’s dignity intact.

There is quiet coordination off camera. Creators swap notes in private messages about safe angles and captioning, and some keep a shared checklist for review, including faces cropped, name tags removed, and institutional signage masked. A few now archive takedown notices with the original cuts to show students why a frame breached a rule. None of this is loud, but it adds up to a working method that lets women be seen as professionals first and as women second.

One stubborn bias is that embalming is “men’s work” because of lifting. The videos answer with tools and teamwork: hoists in prep rooms, slide sheets for transfers, and two-person protocols for heavy moves. Captions note when extra staff are called and why: safety for the living and the dead. By showing risk controls instead of bravado, women recast strength as planning and procedure. That shift matters for younger viewers in the comments. Many ask whether they are “strong enough.” Replies point to training, equipment, and coordination, not body type.

Pathways into the craft are part of the message. In short clips and pinned notes, women break down what an entry really looks like: core skills (restoration, infection control, documentation), basic kit (PPE, hoists, slide sheets), and how a shift runs from intake to handover. Some link to mortuary science programmes and vocational courses, explaining common modules such as restorative art, law and ethics, and health and safety, so school leavers know where to start. A few accounts post “study lists” before exam season and point trainees to practice heads for suturing and camouflage for trauma.

Instead of telling viewers to be tougher, the emphasis is on learning the method, using the right tools, and working in pairs for heavy moves. That practical framing makes the job legible without bravado and puts professional judgement, not physique, at the centre. For students, it turns a vague calling into a map: what to learn, where to train, how to practise safely, and who to ask. It also reframes ambition: less about being brave, more about being methodical.

Deliberately, many of these women keep the visuals neutral. Pan notes in captions that she disables beauty filters, keeps hair tied and nails bare, wears the same dark scrub top, and avoids jewellery. The set stays constant: white light, a plain wall, and a stainless prep table. The aim is to remove cues that trigger threads about looks and keep attention on the method. In her bio she links to a two-line code of conduct (no faces or identifiers; consent logged) and a short FAQ about physical strength, pay and training routes. When questions drift to appearance, she pins a reminder: Focus on the procedure. That discipline reads as authority, so viewers learn to expect checklists rather than performances, and students treat the account as a reference.

The neutral set also makes the clips easier to moderate and reuse. Even lighting prevents colour shifts that could sensationalise bruising. A fixed frame keeps edits traceable. Step labels let her trim sensitive shots without losing the thread. The cumulative effect is a style that is recognisably hers, and straightforward for others to text within the rules.

Ethics are built into the workflow. Before filming, creators run a short checklist: log consent, remove identifiers for the deceased and family, mask institutional signage, and review shots for avoidable distress. If a frame risks recognition, they swap it for narration or a diagram. If a family later withdraws consent, the clip comes down. Several women watermark teaching cuts and keep a simple consent log that lists the time, the purpose of use, and a contact on file, so students can learn while privacy holds.

They also post reminders that their videos are explanations, not instructions for use at home. For decisions, they signpost viewers to licensed funeral homes. The effect is cumulative: a house style that is neat, neutral and auditable. It creates a public record that shows authority not only in technique but also in how boundaries are kept. Several creators also publish a brief explainer on removals for families. It sets out who to call, what paperwork is needed, and how consent is recorded, so the practical steps are clear before grief peaks. Making that pathway visible reduces panic without exposing private details.

Researchers of death and media say short-video platforms widen who gets to depict death work. Some authority shifts from institutions to individual practitioners, women included. Pan Honglei’s practice echoes that shift: a process-first lens, a neutral set, and rules that keep dignity at the centre.

On Douyin, violent or discomforting imagery and sensitive medical content are restricted under the platform’s community conventions, so most creators adapt: hands-and-tools shots, step-by-step narration, and no faces or IDs. Visibility also brings pressure. After a few clips were removed for sensitive imagery, Pan says she now edits more tightly and predicts what might be flagged, swapping shots for narration or diagrams when needed. As attention grows, some comments read her through gender first; she leaves those aside and keeps the focus on procedure and boundaries.

“We always say that we should speak out bravely,” she said, “but women’s expressions are often labelled as gender. I don’t want this profession to be seen for a while because of a high-traffic video. I hope that one day people can truly respect this profession and respect women for doing this profession.

The appearance of a female funeral embalmer like Pan Honglei on the short video platform is not the first time that the public has “seen” this profession, but it is the first time that people have rethought: how do we “see” them? It is not voyeurism, nor a prepackaged “professional” image; it returns to the everyday work of embalmers as a craft. This change in the way of viewing may also mean that society is gradually updating this professional cognitive model. I just focussed the camera on my work, not me,” Pan Honglei said. “I also hope that the eyes of the audience outside the camera can be focussed on our hands, not our gender.”

“Watching” on social media is a kind of public behaviour, but in the funeral industry, it has also restructured the boundaries between private and professional. Recent research shows that social media is bringing funeral labour from private or backstage settings into public view, while the growing presence of women in funeral service reshapes who is seen doing this work.

Like Pan Honglei, there are many female funeral embalmers who publish their works on Douyin. Their video content covers many levels, such as technical operations, ethical norms, and cultural details, from makeup techniques to camouflage for trauma, to the choice of wording when communicating with family members, to how to deal with farewell ceremonies of different beliefs. Therefore, the audience can be exposed to the knowledge and processes that have only been disseminated within the industry in the past. This kind of professional display for the public allows the funeral industry to gradually get rid of the mysterious filter and display it more directly in front of the audience.

“I’m not alone,” Pan Honglei said. “In the past, the profession of funeral embalmers was rarely seen. Now, not only are more and more funeral embalmers posting videos, but many female funeral embalmers have also begun to take videos to record their work like me. Sometimes we also send private messages to encourage each other to learn from each other’s experience, which gives me a lot of motivation to continue filming.” Outside the profession, these interactions also slowly form a stable and gentle connection between female practitioners.

These female funeral embalmers seen on Douyin constitute a specific and true career record of women in this industry. They use content to respond to the society’s stereotypes of the funeral industry and gender roles so that the public gradually regards the profession of embalmers as a professional, understandable, and respected position. “I hope that one day when you see the female funeral embalmers, you will no longer think that ‘she is a female’ but say ‘she is really professional.’” Pan Honglei said.