The abducting and hiding of children by fathers is a common case in China, but it is difficult for a judge to implement punishment. How hard is it for mothers who have lost contact with their children to pursue legal rights?

Jia Liang, 34, from Beijing, China, takes shelter from the rain in a small park in France, and her tiny frame curled under an open umbrella.

In a little over an hour, she would cross the street to a social center to meet her child. According to Liang, her son was abducted from China and hidden in France two years ago by his biological father Cao Liu.

Following a French court ruling, she can now visit her child for two hours every two weeks.

Although she went to the police in China immediately after the abduction in April 2019, and filed a lawsuit against the man, the case has not been tried in China. “I filed to have the case dropped in China, even though I wanted to fight the legal process,” she said.

“If you look at Xiaolei Dai, she has litigated in China for seven years, but it means nothing.”

In order to fight for custody, she decided to move from Beijing to France without knowing French.

Custody goes to abductors

The woman, Dai, 41, also from Beijing, discovered her son had been suddenly abducted and hidden by his biological father, Bailuo Bi, before they officially divorced in 2014.

She fought for seven years to get custody, or just normal access to her child.

“But I can’t get any particularly good results. Wasted years and years,” she said.

Last year, the two women met because of a common encounter.

“One of the most painful things for a mother is to let her lose her own kid,” said Dai.

“‘ You come to me and I won’t let you see the baby, you can do whatever you want ‘, Bi kept telling me.”

After a life of severe domestic violence led by Bi, she filed for divorce and claimed custody of the child.

However, when she learned about Chinese law, she dropped the case after her first appeal. “Because if the child is living with the father during divorce, he is likely to get custody,” said Dai.

According to a legal report on parental child abduction in China, the biggest basis for Chinese judges to decide on custody rights is whether they live with the child, which means that when fighting for custody, the person who is living with the child has an advantage.

Liang’s experience proves this to some extent. “A Chinese judge said if I had to sue Liu, he would have to give my son to the father,” she said.

“Because the kid is in France with Liu. If the custody is awarded to me, the judge cannot go abroad to retrieve and return him to me.”

“My case would be completely different if China were in Hague Abduction Convention,” said Liang.

It is a multilateral treaty established in 1980 to protect children under 16 years of age from illegal removal or detention at the international level and to establish civil procedures to ensure the prompt return of children to their country of habitual residence.

The convention stipulates that if a parent takes a child out of the country without authorization, the child should be immediately returned to the country of origin.

“At first I didn’t know that in China: biological parents who abduct their children are not punished by law,” said Dai.

Dai’s friends advised her to resue after she found the child. She took the advice.

Months later, Bi was still abducting and hiding the boy, but he filed a lawsuit. “It ended up that I was the defendant, and he was the accuser,” she said.

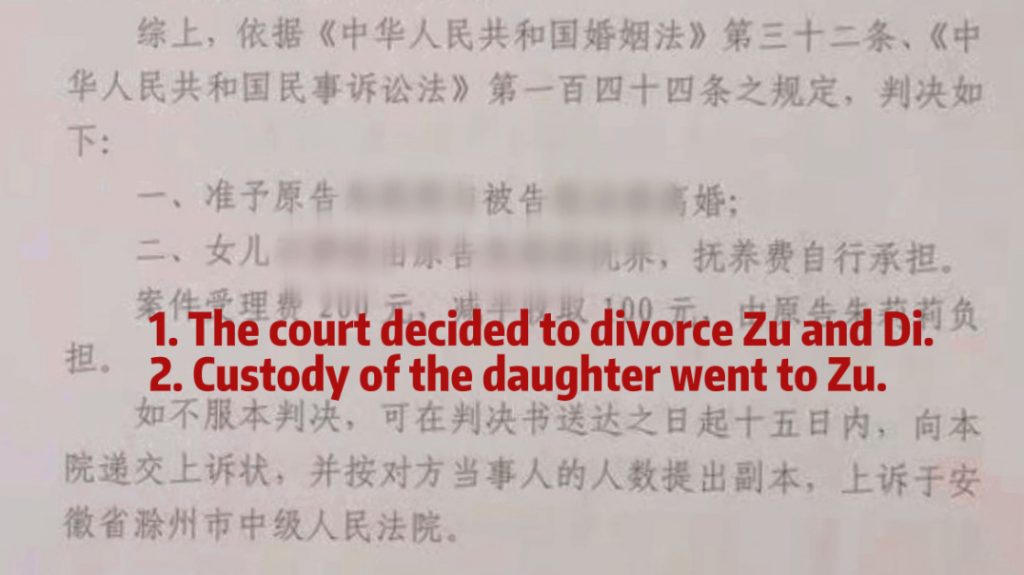

A year and a half later, Dai received the verdict and they divorced, but Bi was granted custody.

“I find it incredible,” said Dai. “And there’s not a word in the judgment about my visitation rights.”

Dai had no choice but to find a new well-known lawyer familiar with such cases and file another appeal.

“But the second trial upheld it, and then the supreme court upheld it. Not once was there for me,” she said.

“Many people told me that in China, unless there are special circumstances, the verdict of the first instance is usually final. There is no need to continue the appeal.”

In China, the possibility of a second trial changing a sentence is low. According to the 2019 Judicial Statistics Bulletin of Chinese courts released by the Supreme People’s Court of the country, there is only a 5% chance that the verdict will be changed in the second instance.

Dai has also made several attempts to meet her child privately, but Bi and his family have refused. “They beat me whenever I went,” she said.

Since Dai’s visitation rights were not specified in the first ruling, “there was no way the court’s staff could help me,” she said.

It was three years before Dai saw her son again. They only spent an hour together. “The kid doesn’t know me anymore,” she said.

Getting custody is not getting children

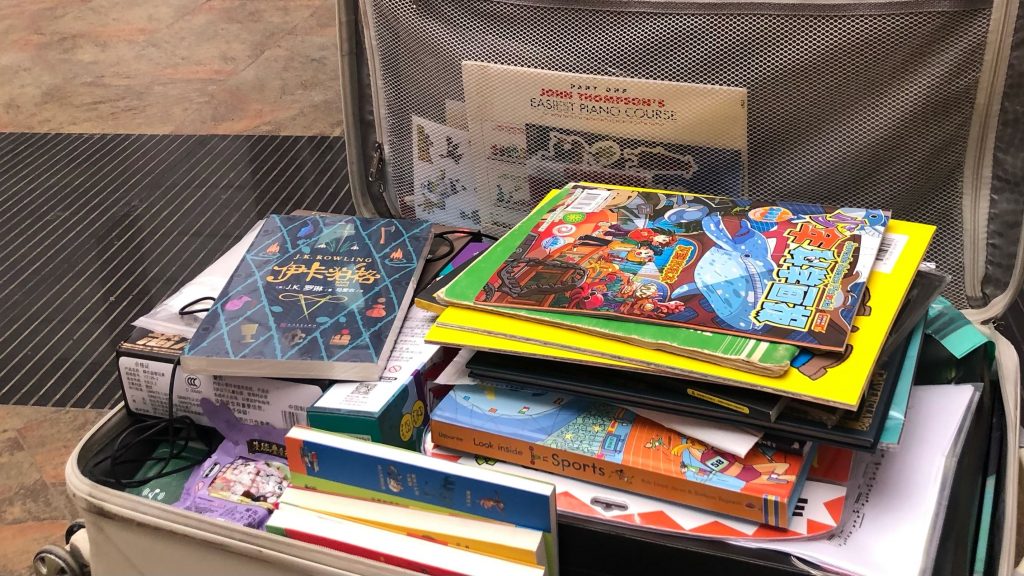

Unlike Dai, Li Zu, 32, from Chuzhou, Anhui province, appears to have won the tug of war: she has been granted custody of her daughter. The child had been abducted and hidden by her ex-husband, Zhang Di.

However, when she went to Di’s house to look for the child, she found that both the child and her ex-husband had disappeared.

Zu decided to apply to the court for compulsory execution, through the help of the judge to find the missing child.

“Execiton means that Chinese People’s Court of China, in accordance with legal procedures, makes use of the national compulsory force and makes clear the specific execution content in the judgment to force the obligor to complete its obligations, so as to ensure the realization of the right holder’s rights,” said Xiao Chen, a Chinese lawyer focus on custody cases.

“My judge told me to find the exact address where Di was, and then he could go there and help me find the kid,” said Zu.

After receiving the message from the judge, Zu seemed to get Sherlock Holmes-like abilities in the desperate situation. Suzhou, Jiangsu Province – she locked this position, which was the place where one of Di’s brothers lives.

“I went to that region to report it to the police, who were very helpful,” said Zu. The police who received the call questioned her carefully. “They found the place where Di left his last footprints on the computer, and I went there.”

Zu has been staking out near the apartment where Di lives, “but I haven’t seen my daughter,” she said, before appealing to nearby residents. “I even knelt down to one person, asking her to help me.”

The woman eventually told Zu that the baby, Di, and Di’s mother have indeed been around here. Zu sensed a glimmer of hope and told her judge the news.

“I messaged him that he needed to go to Suzhou with relevant documents so that the local police could help us,” said Zu.

“He came, but he didn’t bring any papers, and the child still hasn’t been seen.”

Later, Zu reported him to the authorities.

“I said to him, ‘it’s not to report you, but calling for help. It’s something you’ve been putting off, ‘” she said. “If he doesn’t act, I’ll go to the central authorities in Beijing.”

The judge told Anhui Radio and Television that if the child does not want to go with her, he can not enforce the child.

“I told the judge to follow the verdict,” Zu said. “It’s normal for the kid not to know me, we haven’t seen each other for two years. And the child has no blood relationship with Di.”

The baby’s biological father is her former, and she left him because of domestic violence. She met Di through a social media app, Wechat, when she was nearly three months pregnant.

According to the judgment of the Mingguang People’s Court in Anhui Province, Di understood this and was willing to form a family with Zu.

“This means that although the child is not genetically related to Di, the child is legally considered their wedlock child,” said Chen.

The good times did not last long. Their different attitudes towards life filled them with contradictions.

Countless quarrels, like a downpour, quenched the flames of love. Finally, Di abducted the child while Zu was away at work

Two years later, Zu finally met her daughter in a court-arranged mediation room. “I gave her a big hug and she didn’t reject me,” said Zu. Di was also present, and tried to stop the mother-daughter interaction, but was stopped by the bailiff, she said.

“The judge asked my kid who I was, and she said, ‘this is my mother’,” said Zu. “He continued to ask her if she missed me and she said, ‘I miss her’.”

However, according to Zu, while she communicated enthusiastically with the child, the judge began to ask the child questions alone, and later left the child with Di. “They cut me off from the kid,” said Zu.

Then, she said, she heard Di tell her daughter: don’t go with your mother.

Zu crashed. “I asked the judge: can’t you hear what Di is saying to my kid?” she said. “He didn’t stop it at all.”

Footage from the surveillance showed the child crying in horror at the chaotic scene. Several bailiffs stopped Zu, while others told Di to take the girl quickly, she said.

“When my kid and I were close, they didn’t act. When the kid began to cry, they started to act, ” said Zu. She questioned the validity of the procedure.

This time, she was unable to successfully reunite with her child.

A Chinese lawyer, Renbao Li, believed that as a judge, certain coercive measures, including fines and judicial detention, can be taken against the father who refused to comply with the verdict to promote him to return the child. Because Zu already had custody.

“But the court staff would say this is hopeless,” said Dai. “To them, we’re just order numbers waiting in line for a verdict or act.”

These orders pile up on the desks of the staff and they have to deal with them one by one.

“They tell the father who abducted the child to bring the child to the court and spend an hour or two with the mother, and then the work is done,” said Dai.

“I also need to sign to prove my meeting with my child is over.”

But is it really over?

In those seven years, Dai saw her child only six times, for a total of no more than 30 hours.

She kept thinking about how to get back the time she lost contact with her son while she waited for the judge to process her order.

But no one could give her an answer.