Thousands of people still attend the free 5km event each week despite a Covid fuelled dip in attendance. What does it bring to people’s lives?

On a Saturday morning in the 90-acre estate at Tredegar House in Newport, David Sinclair stood among a sea of runners and waited. Some people jogged on the spot, others stood with hands poised over their stopwatches, ready to track their time and hoping for a personal best. David stood in woolen jogging bottoms and held a bike water bottle that was too big for his hand. He may have completed the Couch to 5K programme but he was still nervous and so his bottle went with him for comfort – no matter the weather, no matter the distance.

David had never enjoyed sports. The environment at school was toxic and homophobic and that had stuck with him. It wasn’t until he was nearing forty and needed to do something about his high blood pressure that he took up running. And so, he stood, at his second ever parkrun, waiting for the whistle to blow.

Fast forward ten years to 2022 and David is running a bit more than 5km. A marathon runner, an ultra-marathon runner and a coach, David is a true running convert. And yet, every Saturday morning he still completes a parkrun. “It’s an incredible start to the weekend. I would feel a bit lost without it,” says David. “Unless there’s something stopping me, I’ll be at parkrun every Saturday morning.” He just ran his 250th parkrun this May in Newport.

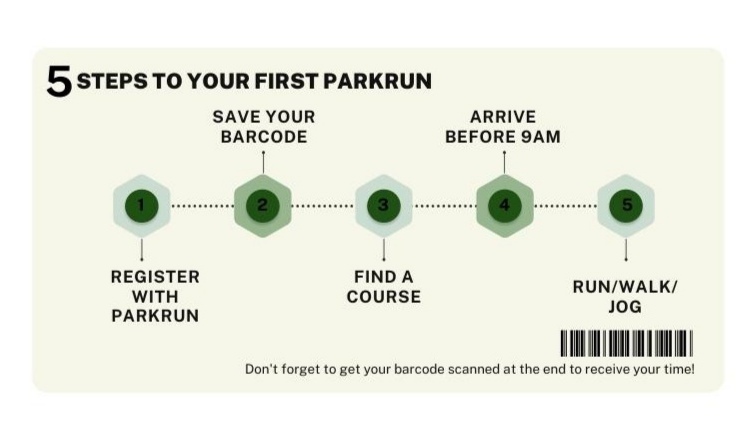

Parkrun is a simple concept. People can sign up to run, jog, walk or watch a free 5km course that starts at 9am on a Saturday or Sunday morning and is organised by volunteers, many of them runners themselves. It started in 2004 in Bushy Park in London and has since grown to over 1,000 courses in the UK and has been exported to more than 20 countries around the world.

David thinks the popularity of parkrun lies in bringing people together. “I think it’s very important for the community in general,” he says. “You’re just getting together with mates and doing something you like.”

It’s also not restrictive as no matter what your fitness level is, you can come along and get involved. This is part of the ethos of parkrun, which puts wellbeing and inclusiveness above speed – “what matters is taking part”. David agrees. “You might be going for your fastest time, or you might be just back into running so you’re just happy to run around. You might walk the course which parkrun encourage as well,” he says. “People can treat parkrun however they want.”

Tim Gardiner does just that. He doesn’t consider himself a “serious runner” but is a parkrun advocate. In fact, he doesn’t even really like running. “There’s no fun in running. The fun is actually parkrun, the bit round the edge,” says Tim. “If it wasn’t for parkrun I wouldn’t be running. I’m not going to pay to enter a race.”

For Tim parkrun doesn’t mean just showing up at his local course in Essex each week, it’s a chance to travel, a chance to do a bit of writing. “I got a bit bored of running the same one, so I thought I’ll start travelling,” says Tim, who has completed 77 different parkruns across the UK (and one in Japan). He also writes about his experiences, creating “parkrun poetry”.

Tim’s writing is a mixture of race reports, which include statistics and details about a specific parkrun including fastest runner, the number of participants, and experiences of his travel. All come with a creative twist. From Glastonbury parkrun there was a festival feel report, from Stratford-upon-Avon, a report written like a play by the Bard, AKA The Taming of the Shoe and in Whitby, a report in the style of the novel, Dracula. The latter even came to life. “I pretended – obviously – I was Dracula because I had a cape on and everything. I ran it like that, then I wrote it as Dracula,” says Tim.

From the running to the writing, Tim won’t stop until he reaches at least 100 parkruns. “It’s addictive,” he says. Travelling for parkruns is not unique to Tim, it’s a parkrun subculture known as parkrun tourism, and those that do it dub themselves parkrun tourists. There is even a Facebook group for parkrun tourism across the world.

David travels too. He’s completed nearly 50 different courses across the UK and loves the variety on offer, from sand dunes and mountains to lakes and roads. He also loves the chance to meet new participants and volunteers. “It’s really nice to meet the volunteer teams when you do a different course. They’re genuinely so happy to chat and see that people have come to run at their parkrun,” says David. “It’s contact with people as well. Some people don’t see people a lot of the time.”

Tim usually travels alone and visits places he wants to see rather than just a “random field”. Whilst he does use it to meet new people it’s more a way to get out and about, particularly as things have been difficult lately. “At this point in my life, life is not good to be honest. I have mental health issues. My parents’ health is failing etc. My mood is not great after Covid. And it’s just an escape.”

Many people in the UK have suffered with their mental wellbeing over the last two years. In the first year of the pandemic alone, anxiety and depression increased by 25% worldwide according to statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO).

Parkrun was also affected. It was shut down for 18 months due to Government restrictions and when it did return in late 2021 there were 15% fewer participants according to Parkrun Global, the charity behind the initiative.

Despite the reported downturn, parkrun has managed to attract newcomers. Ian Greenman is one of them. A retired firefighter from Bridgend, Ian first went to a parkrun with his daughter. It was something for them to do when they still lived under the same roof and now it’s a chance to meet up halfway between their houses on a Saturday morning and get some miles in for their upcoming half marathon.

Ian has been a keen sportsman for most of his life but he thinks parkrun is unique. “It blows me away. The organisation that goes into a parkrun every week, the volunteers who marshal the route, the pre-parkrun brief, the encouragement throughout, the support at the end. It’s fantastic,” he says. “I think it’s amazing how each parkrun is facilitated and coordinated.”

Volunteers are a huge part of parkrun, from setting up the events, timekeeping, marshaling and scanning barcodes at the completion of the course. It’s seen as another way to give back and get involved and it makes a big difference.

One volunteer acts as a sort of parkrun mascot for Ian. A young man, hair in a top knot, holding a boom box who cheers and dances to his own beat at the sidelines is as much of a marker as every kilometre completed. Even if his favouritism is a bit “unfair” to other marshals it’s all part of the magic.

So is the fact that his daughter still wants to run with her “old man”. “It goes back to Covid,” says Ian. “Loss of loved ones in recent times. It brings it home just how important family is and being able to do things together. Albeit in tiny little pockets. Just creating nice special memories.”

Tim also runs parkrun with his son – on the weeks he isn’t travelling. At twelve years old he’s already showing promise. “He runs a six-minute mile now. That’s impressive,” he says. Tim, however, is just focusing on completing his 23 parkruns to get to the hundred rather than his speed, “I’m getting too old. My knees could pack up at any point,” he says. “I don’t really want to mess them up.”

David also needs to look after his body but it’s not because of his blood pressure anymore. He has an ultramarathon coming up soon and rest is key according to his coach. That rule just doesn’t apply to parkrun, a simple pleasure. “There is this thing every Saturday at nine o’clock. If you want to be there you can be there, and everyone will welcome you,” says David. “That’s it and that’s great.”

Parkrun UK: a running commentary (in photos)