As experts start to warn about the negative impact of Chinese volunteer projects on underdeveloped countries, what needs to happen to help the recipient communities?

One night, at a construction site in Tanzania, a group of men is knocking down a brick wall that was built during the day and rebuilding it. They smashed the crooked walls with a hammer, plastered the bricks with cement, and carefully built them up again. The new walls are even neater than the original ones.

This project is for a library of the local orphanage. It involves a group of US high school students who volunteer at the orphanage. During the day, the volunteers spend six hours mixing cement and laying bricks. But the men will have to redo it all in the evening.

Pippa Biddle was one of these volunteers who went to Tanzania to volunteer at the orphanage. Every morning she woke up to see a neatly rebuilt brick wall. “We were told they would have to redo that one,” she says.

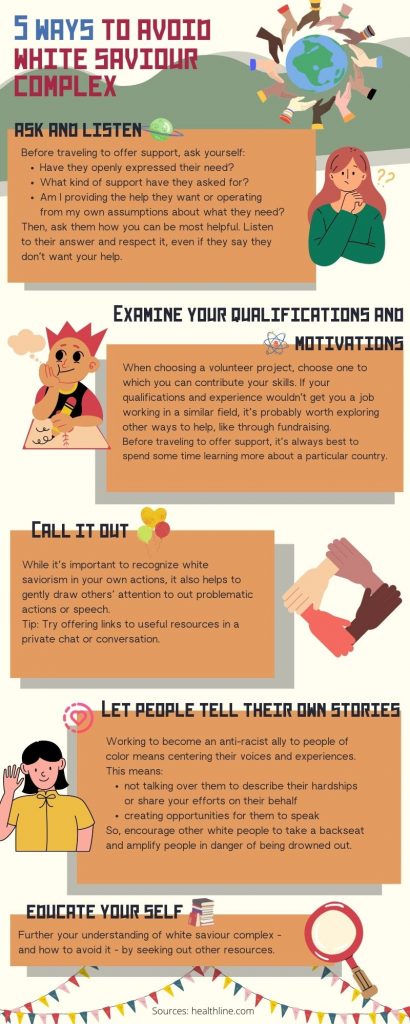

According to Pippa Biddle, projects like this are very common in volunteer tourism. Volunteers from powerful countries believe that their arrival will be helpful for the locals. But they usually lack the professional skills needed for volunteer projects, making many projects ineffective.

Young people like Pippa Biddle who go to underdeveloped countries to volunteer are common in western countries. They call this activity volunteer tourism or voluntourism. Since volunteer tourism originated in the West, it was usually well-educated young white people from developed countries who participated.

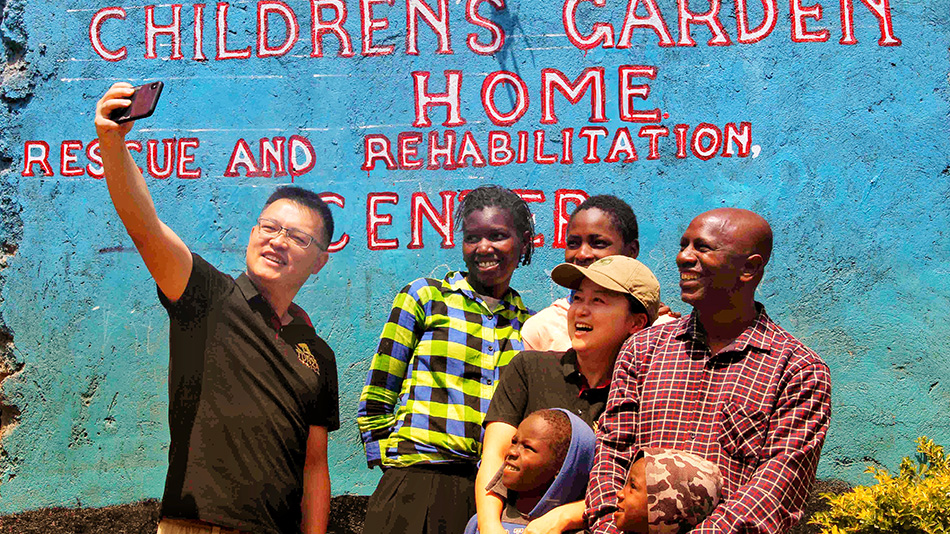

But in recent years, as the country’s economy has grown, many Chinese volunteers have joined these transnational volunteering projects. Volunteer tourism in China has grown rapidly over the past decade, with the emergence of many organisations offering overseas volunteering projects.

Gapper is one of these Chinese volunteer organisations. Founded in 2012, the organisation has sent more than 82,000 Chinese volunteers overseas in the last ten years. These volunteers are mostly young, educated students. They travel to Southeast Asian countries such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Nepal to work on teaching and orphanage projects.

However, the aid approach of sending volunteers from powerful countries to underdeveloped countries has also come under some scepticism. Voluntourism has been criticised for perpetuating the stereotype of the white saviour complex, which comes from the many injustices of the colonial period.

As early as 1997, the American historian Elisabeth Cobbs Hoffman pointed out in her research that the US Peace Corps was a politically and colonial-like programme.

Founded by former US President John F. Kennedy in 1961, the Peace Corps has sent 240,000 American volunteers to 142 countries worldwide. The first country to receive Peace Corps volunteers was Ghana. And the Ghanian Times, an influential newspaper in the country, publicly denounced the Peace Corps as an “agency of neo-colonialism”.

However, Pippa Biddle, now an author of a book on volunteer tourism, suggests that the whole idea of colonialism as being a white and European practice is now a really outdated understanding. She claims that as China became a world superpower, people from the country started to volunteer abroad. They may face a similar problem with the West, a privileged saviour complex.

Pippa Biddle believes that simply using whiteness as the metric is extraordinarily misguided, and the privileged saviour complex is now even more of a universal problem. “Anyone who has privilege going into a community that is not their own and exercising a level of control or trying to direct the way those people’s lives will go is problematic and is really rife with issues,” she says.

According to Pippa Biddle, as China becomes more economically and politically powerful, China’s sending of volunteers is becoming another form of colonialism. And the Chinese volunteers will inevitably fall into the privileged saviour complex when supporting underprivileged countries.

“The Chinese government and the Chinese outward-facing apparatus have been heavily interested in development initiatives in countries with large amounts of resources for a long, long time. This is just another way to do that,” says Pippa Biddle, “They are practising a method of exerting influence on countries and communities that are not their own for the purpose of financial gain. That is colonialism.”

Liu Liangbin, the founder of a Chinese volunteer organisation, has a different take on Pippa Biddle’s claims. “I don’t think we Chinese have a saviour complex. But the process of volunteering somehow creates this feeling. It is not only in China. It is also a global problem that is hard to avoid,” he says, “And the word colonialism does not come from China. Colonialism is one country’s domination over another, but China has never dominated another country since ancient times.”

But he believes that as China’s economic power grows, young people in China should take on more responsibility. He encourages young Chinese people to volunteer, as it is an excellent opportunity to help those in need in other countries. “Becoming a super economic power is not just an honour. It also means taking on more responsibility. We need more young Chinese to take to the international stage and participate in global governance,” he says.

According to a study on volunteer tourism in China in 2014, A sense of responsibility is a typical motivation that drives young Chinese people to participate in volunteer projects.

However, Liangbin also acknowledged that some Chinese people, influenced by negative media reports, are prejudiced against third-world countries. The prejudice stems from a lack of knowledge of the local culture and the real needs of the local people, according to Liangbin.

According to a recent study published in the Third World journal, Chinese volunteers and organisations lack an understanding of the need of the recipient communities. Their objectives are not negotiated and agreed upon with the local people. The communication between the volunteers and the recipient community was a one-way flow. The locals had no channels to provide feedback or options to choose from.

I didn’t know what I needed to do or what they needed. All I know is that the children love stationery, and if you give them an eraser, they will be happy. They never seem to have enough of those things

Li Tiange, who joined a volunteer teaching project in Sri Lanka in 2019

Tiange knows little about what the children need, but she believes that she was doing a good deed by bringing joy to the children. “I think it’s hard to say whether I helped them or not, but I think they should have been quite happy with me,” she says.

However, believing oneself is doing good without knowing what the recipient communities need and want is one of the manifestations of the white saviour complex, according to Ranjan Bandyopadhyay, an expert on volunteer tourism.

A lack of local knowledge will result in some volunteers thinking of themselves as givers from a privileged or powerful country, according to Liangbin. He suggests that Chinese volunteer organisations should train their volunteers in cross-cultural communication skills before sending them overseas.

“If they lack cross-cultural communication skills and do not understand the local culture, volunteers may unconsciously perceive themselves as givers or a do-gooder, which can actually hurt the self-esteem of the people in the recipient community,” says Liangbin, “It is important that the local people should be treated equally in volunteer activities, and the volunteers should communicate with them on an equal footing.”

While people in underprivileged communities are the ones being assisted, volunteers usually have more power in volunteering. And the intensified disparities of power due to volunteers’ lack of knowledge of the recipient community is a classic manifestation of the white saviour complex, according to a study from 2019.

Although there are still many issues that need to be addressed in China’s volunteer tourism sector, according to Liangbin. He claims that Chinese people have some misunderstandings and prejudices against people of certain countries, but not to the extent of having a privileged saviour complex.

“Because we are influenced by traditional Eastern philosophy, there is no law of the jungle in our culture, no discrimination against people from other countries, and no saviour complex. But there are prejudices against people from certain countries,” says Liangbin, “Both volunteers and organisations should do what they can to reduce prejudice, which is essential.”

In addition to volunteer activities, Liangbin hopes to see more young Chinese people in international activities. “In any case, I encourage young people in China to visit foreign countries. The world is so big, and there are not only developed countries,” he says. “You can only see the real situation if you go to a third-world country and realise that there are still people living on just one dollar a day.”

Pippa Biddle is now still committed to research in the field of volunteer tourism and published a book, Ours to Explore: privilege, power, and the paradox of voluntourism. “I did not expect to blow up the voluntourism space because you don’t blow up a multi-billion-dollar industry with one book. But it has started a lot more conversations. And I really appreciate that,” she says.

Recognising from her own experience the shortcomings of the volunteer tourism industry, Pippa Biddle now recommends volunteers who really want to help others to be well prepared before taking part in projects.

“I will recommend people first find an organisation in your local community that you want to volunteer with and commit to working with them regularly. And pursue a field that will empower you to have the skills that you want to have, to be able to make a difference as an international volunteer,” she says.