Amidst an impending war and political tension, Ethiopia finds solace in Bollywood films as the passion for the cult classics lives on. How well does the youth from this unlikely destination cope with the nuances of language and culture?

For the past four years, Ethiopians have grappled with the constant fear of a civil war as ethnopolitical conflicts rise in their regions. The country’s youth live in a dilemma, wondering if they could soon be recruited to fight, yet their age-old love for the biggest film industry keeps their zeal alive in the capital city of Addis Ababa.

The world expected the importance of film theatres to die out as the pandemic turned viewers to video-streaming services and apps. Yet, Ethiopia celebrated a joyous moment in the history of Bollywood as it released its first Indian film on the cinema screens a couple of months ago. It was the first time East Africa had seen a Bollywood film grace its theatres simultaneously with the rest of the world.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes as I saw videos of people back home watching a Bollywood movie on cinema screens and over 500 people dancing to a classic SRK track in the theatre,” said Mogus Zelalem, a native of Addis Ababa, currently living in London.

Rajkumar Hirani’s directorial ‘Dunki’ was released in Ethiopian theatres following the release of ‘Tiger 3’ last year, receiving widespread love from fans. A video surfaced on X (Twitter) where a crowd of people were dancing to the song “Lutt Putt Gaya” featured in the film. They mimicked Bollywood star Shah Rukh Khan (SRK)’s steps and rejoiced at the music they have loved for decades.

“Of course, it was superstar Shah Rukh Khan’s film to debut in our theatres, he has been my favourite since the 1990s. Although I am away from home, this is a huge moment for me as I can feel the excitement these people feel during this cinematic experience,” said 38-year-old Mogus.

Spending most of his formative life in the Ethiopian capital till the age of 20, Mogus was a quintessential ‘Addis city boy’ with a keen interest in football and sneaking out to watch films in the bustling video houses. Like every other urban Ethiopian youngster, the films of this estranged language appealed to him more than any Hollywood piece.

SRK’s eyes were expressive enough for me to understand the love he had for his heroine…

Mogus Zelalem

“I used to skip classes to go for Bollywood screenings in the Addis Ketema neighbourhood almost every week to see an Indian movie. My fondest memories include cheering on and clapping with my friends at intense action sequences,” said Mogus. “I can name every Bollywood superstar of that time from Amitabh Bachchan to Kareena Kapoor and sing along to popular Hindi songs from that time,” he said, humming the tune to 2000’s ‘Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai’.

The screenings at video houses of cities such as Addis Ababa, Adama, and Dire Dawa cost about 1-5 Birr (less than 50p) and were hardly an ordinary affair. It wasn’t subtitles that translated the Hindi to the local Amharic language, rather it was just an untrained interpreter who would loosely translate the dialogues. He would sit in front of the screen and speak loud enough for the hundreds of people in the room to hear him translating.

“The regular screenings in the capital’s Cinema Ethiopia and Merkato became very popular despite the translator’s poor skills. The songs, the actors’ reactions and settings were enough for us to guess the premise of the movie,” said Mogus. “SRK’s eyes were expressive enough for me to understand the love he had for his heroine,” he laughed, talking about Shah Rukh Khan.

The interpreters had little to no knowledge of the Hindi language or Indian society, yet repeatedly translating these films made them almost perfect at their jobs. Some translators in the business would read about India to get a better idea of its culture and improve their interpretation of the content. Translators such as Kasim Mecca, Seleshi Dabi and Getachew Diriba were common household names in the city.

The ‘stardom effect’ lingers on in East Africa, as they readily go to the theatres to watch ‘The Khans’

Ayanjit Sen

“It wasn’t just the local interpreters that would become adept in translating the classic movies,” said Teshoma Assefa, a local businessman from Addis Ababa. “I had watched 15 movies by the age of 21 and wanted my mother to get a taste of Bollywood films so I rented a CD of Mr. India from Africa’s biggest open market, Merkato.” By then, Teshoma could interpret most of the film by himself to his mother.

The video houses showing these films were major social hubs too as men and boys would catch up with their friends. However, there were common sightings of neighbourhood ‘thugs’ or people consuming the local ‘khat’ drug from East Africa, recalled Teshoma about why women and children were often discouraged from attending these screenings.

“Watching Hindi films was a divine experience on its own for its colourful sets and emotional backdrops. We Ethiopians could relate more to the Indian culture as it depicted spirituality, joint families, patriarchy and respect for elders in its films. It was not the same with films from other countries,” added Teshoma.

I wanted my mother to get a taste of Bollywood films so I rented a CD of Mr. India from Merkato

Teshoma Assefa

He revealed that one of the best decisions he made was to collect CDs of these Bollywood films as the city saw a decline in live interpreting in video houses with the emergence of technology and a rise in political tension. However, the live interpreters continue to translate these movies on live Telegram sessions, or videos they upload on YouTube.

“I still follow ‘Wase Records’ on Telegram as they were one of the best translators, and view TikTok videos featuring similar translations,” Teshoma said. “I am glad I spent those 500 Birrs on my favourite Indian movies to watch whenever I want.”

India has crossed various borders in the past century through its films, making Bollywood the biggest film industry in the world. Indian digital journalist and film strategist Ayanjit Sen talks about the ‘Indian Stardom effect’ and how it has helped the industry break linguistic and cultural barriers to reach different parts of the world.

“Following the COVID-19 pandemic, Indians prefer watching more story-driven films than star-driven ones, unlike the current scenario in East Africa,” said Sen. “The ‘stardom effect’ lingers on in East Africa, as they readily go to the theatres to watch films featuring stars like ‘The Khans’, creating a dichotomy as Indians visibly condemn star-driven films.”

Speaking of the age-old charisma and talent of Bollywood stars, Sen points out how the “individual appeal towards these movie stars has continued to charm viewers in Africa and push them to be just as excited about Bollywood as before.”

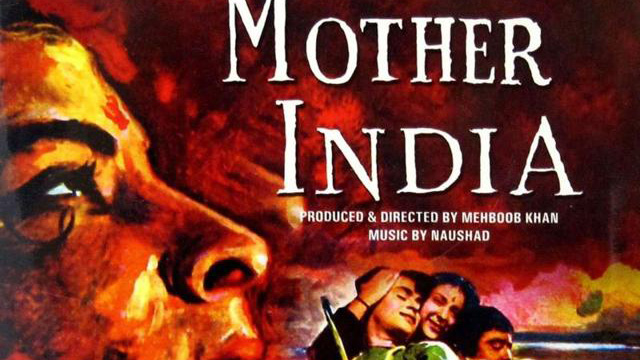

From old hits such as 1957’s ‘Mother India’ featuring Nargis to classic 2000s romances like ‘Fanaa’ and ‘Mujhse Shaadi Karogi’, along with Shah Rukh Khan hits such as ‘Kuch Kuch Hota Hai’ and ‘Mohabbatein’, the youth cherished the three-hour long sittings in the cinema parlours.

“We love everything about Indian movies from the romance, actions, culture, and especially the music and dance sequences which we enjoyed the most,” said Teshoma. “No Hollywood movie could ever match this level of entertainment.”