When subsidies favour meat over plant-based alternatives by millions, retailers demand higher margins from vegan products. When the system stacks the deck, is the choice really yours?

“There are significant subsidies that are open to animal farming that are not, um, open to, farming for products like redefined meat. Ultimately, that means the cost of beef when it gets on the plate is lower than it should be because it’s been subsidized. In addition to that, the expectation that retailers have on plant based food margins is a lot higher than it is on, say, for example, beef.”

Simon Owen, VP for Redefine Meat Europe, has spent decades in the food industry. His revelation about the hidden economics behind British food choices exposes a system where market forces are anything but natural, and where the loudest voices in the “veganism debate” often have the most to lose financially.

The battle over plant-based food reflects significant economic disparities, with the UK plant-based food market valued at $389.16 million in 2024 and projected to grow at 11.30% CAGR to reach $1,019.97 million by 2033, while supermarkets maintain significantly higher profit margins on plant-based products, with retailers charging margins of 35-50% typical across Europe compared to 8% for animal-based meat products.

Plant-based alternatives regularly cost double the price of their meat equivalents, with vegan sausages priced at twice the cost of pork equivalents, while government agricultural subsidies totaling £2.953 billion in 2023 support traditional farming, with total livestock output reaching £20.1 billion in 2024.

The Subsidy Secret: How Your Taxes Favour Beef

The economics of British food begin long before consumers see prices. Owen’s analysis reveals a fundamental distortion.

“Beef mince in a supermarket is significantly cheaper than it is for a Redefine Meat Mince , because on one side it’s been subsidised, the animal product has been subsidised, and at exactly the same time, the margin that the retailer is wanting to earn from Beef mince is also lower. The expectations are lower. So you’ve got this inequality of pricing, which is a barrier to why more people are not consuming plant based food.”

This creates what economists call “artificial market advantage.” Government agricultural subsidies, worth billions annually, overwhelmingly support traditional livestock farming.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) data shows that direct payments to cattle farmers alone exceeded £500 million in 2023, while innovative plant protein companies receive virtually no equivalent support.

Meanwhile, plant-based alternatives face what Owen describes as “inequality of pricing.” Retailers demand higher profit margins from vegan products, often double those expected from meat equivalents.

The Manchester Closure: When Economics Meet Reality

The stark reality of these economic pressures played out in Manchester when several vegan restaurants closed within months of each other in 2024. The BBC reported on businesses struggling with rent increases, supply chain costs, and what owners described as “margin pressure” from suppliers.

But the closures tell a more complex story than simple market failure.

“There was a real peak in veganism, a real peak in interest in veganism just after the Covid pandemic. Now, there are a number of reasons for that. And personal health may well have been a very strong driver there. But as with any economic fluctuation, you get peaks and troughs and eventually these things level out,” explains Damian Watson, senior PR and media officer from the Vegan Society.

The economic reality became clear when London’s Unity Diner closed, only to reopen due to overwhelming demand. “There was such demand for it to be reopened, and it’s very successful. You must book to gain entry. So I think there’s a natural sort of economic equilibrium that is being found here,” he says.

The Carbon Accounting Revolution

A shift is emerging in corporate Britain that’s changing these economic calculations.

“The biggest benefit that we see, actually, is the number of companies that are wanting to hit net zero in terms of carbon emissions. That’s one of the biggest benefits that we see. Why? Because one of their biggest impacts on their carbon usage is actually their red meat consumption. If you can substitute red meat for Redefine Meat, then actually your carbon emissions can go down quite significantly,” Owen observes.

This trend is reshaping institutional food purchasing. “So we are seeing quite a lot of benefits in that sector. And that comes through in the catering sector, especially when it comes to the health, education and defence sectors. Those three have all got big carbon emission targets. And actually, by reducing their red meat intake, we can really support those carbon emission targets.”

Government procurement rules increasingly factor carbon costs into tendering, creating the first level playing field between plant-based and traditional options in decades.

The Taste Test Deception

Perhaps the most revealing economic dynamic involves consumer perception versus reality. Owen describes systematic testing that exposes the gap between quality and prejudice.

“When we are in the market doing product demonstrations and asking consumer to try for example the Redefine Meat burger we get really positive reactions. When we then tell them its Vegan we get the large majority of consumers really surprised and willing to purchase as they taste great.”

The economic implications are staggering. Products that win blind taste tests lose market share when labeled honestly, creating an impossible business environment that rewards deception over quality.

“We’ve done tastings in places where people have consumed our product and really liked it. And when you’ve told them it was vegan, they can be quite rude to you. They put this openly down to the fact its vegan and not anything to do with whether they enjoyed the New Meat. I have experienced this and you know, they have been openly rude because of the connotations around veganism. And that to me is completely wrong,” he syas.

This reveals how cultural programming overrides economic rationality. On Ocado’s website, Owen’s company has achieved something remarkable. “Our burger is the highest rated burger by consumers than any other burger product. ”

Yet this success hasn’t translated into broader market acceptance due to labeling prejudices.

Owen reveals how companies navigate these economic realities. ” What we actually really do is we talk about how good our food is. Our focus is this great tasting food. That’s our number one element. And that’s because that’s what we believe will make the biggest difference.”

Owen reveals a telling example of this economic strategy. ” I think some consumers are very put off by the word vegan. If we promote our burger with a different title, rather than a vegan burger, for example, a Shock Burger like we did recently at a Theme park but still use the Redefine patty. We sold more than if it was actually called a vegan burger. It was exactly the same product, but the way that we sold the product was without the vegan tag. And ultimately it sells more.”

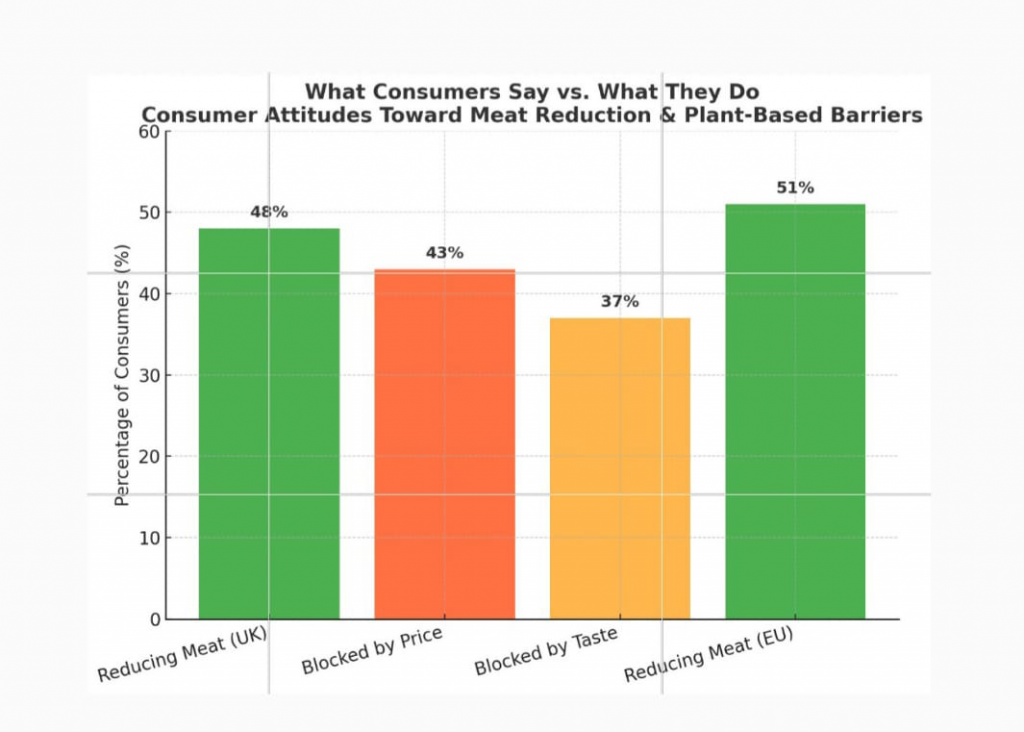

Smart Protein Project (2023–2024), a major EU-funded research initiative led by ProVeg International, which surveyed thousands of UK and European consumers on shifting diets. The research shows that while 48% of UK adults report reducing their meat intake (up from 37% in 2021), barriers such as price (43%) and taste (37%) still limit plant-based adoption. Data from the Good Food Institute Europe (2023) confirms the wider European trend, with 51% of consumers across 10 countries cutting meat compared to the previous year.

The Innovation Investment Paradox

The contrast becomes stark when examining specific cases. While Oatly faced UK boycotts due to its investment ties with Blackstone, a private equity firm linked to Amazon deforestation, traditional dairy companies receive millions in direct subsidies without equivalent scrutiny of their environmental impact.

“Population growth means that actually people’s diets will change and have to change because you cannot support the population growth with an animal diet, it just can’t happen. But also, I think as education and social media keeps teaching people the benefits of plant based and also the negatives around animal meat, ultimately they will have to change,” Owen predicts.

This creates what economists call “transition risk” the danger that current business models become unviable as costs shift. Traditional food companies increasingly face this pressure, explaining intensified resistance to alternatives.

The Health Cost Hidden Equation

Environmental costs add further hidden expenses. The Committee on Climate Change estimates that agriculture produces 12% of UK emissions, with livestock farming responsible for the majority. These costs don’t appear in supermarket prices but get paid through taxes and insurance premiums.

“And one other benefit again on that one is health. So, you know, a current problem within kids diets at the moment is the lack of fibre a, but by moving to a more plant based diet, you automatically increase your fibre intake. And that’s really important to a kid’s health, to everyone’s health. Really,” Owen explains.

Yet school meal contracts still favor traditional suppliers despite public health evidence, demonstrating how established economic relationships override health considerations.

Local vegan businesses face the sharpest end of these economic pressures.

Maddie, co-founder of the vegan skincare business Lilith Natural Beauty, describes her experiences. “Even people that I know well just pass comments and make a joke and be funny, but I also know that just for some reason, you hate the fact that I have chosen to do something that you don’t agree with even at a market stall.”

Archive Chapman, a vegan artisan cheesecake business owner, comes out quite positive on the same.

“I think people are coming round to the idea more and more. You’re seeing more plant based options in restaurants, which is great. Um, more of the bigger chains are offering, uh, more vegan, um, options. So yeah, I think over time people are getting more and more used to it, which is good.”

The Future Market Predictions

Industry analysts predict significant market shifts driven by economic rather than cultural factors. Owen’s smoking analogy is revealing. “I use the analogy a little bit about the smoking culture. So if you go back, when I was ten or eleven to how many people in the UK smoked it was significant. Smoking was huge and people could smoke in houses and in cinemas and work places people didn’t think there was anything wrong with it.”

The economic parallel suggests that cultural change follows economic incentives rather than leading them. “I think the same will happen with plant based eating. I think people will go, actually, what we do in terms of the impact on the environment, the impact on animals. It is wrong,” he says.

Market indicators support this prediction. The UK oat milk market demonstrated a compound annual growth rate of 14.14% during 2020-2023. Meanwhile, GFI Europe’s analysis of retail data shows that while plant-based milk sales experienced some decline in 2023, the drops were significantly smaller than the previous year, suggesting market stabilisation.

The Consumer Revelation

Perhaps the most significant finding is how little consumers understand these hidden economic factors. Price signals that should guide rational choices are distorted by subsidies, margins, and regulatory capture that operate invisibly.

Owen’s taste test experiences reveal consumers making decisions based on incomplete information.

“I think people will eventually end up replacing it with traditional meat. Like if this is the taste and quality they get and we’ve already had consumers say that. They buy our burger rather because it tastes good and they will put it on the barbecue, or they have it once a week because it’s so much better than the meat alternative. That is success. And we will continue to do that,” he says.

When economic distortions are removed, when people judge products on quality and price rather than prejudice, plant alternatives often win. This suggests that current market outcomes reflect economic manipulation rather than genuine consumer preference.

The question isn’t whether veganism belongs in culture wars, it’s whether British consumers deserve to know the economic forces shaping their food choices.

Instead, British food operates in a rigged system where government subsidies, retail margins, and corporate lobbying predetermine outcomes before consumers even enter the supermarket.

As Simon Owen reflects on the broader implications.

“So yes, I do think there are a few things. Population growth means that actually people’s diets will change and have to change because you cannot support the population growth with an animal diet, it just can’t happen. But also, I think as education and social media keeps teaching people the benefits of plant based and also the negatives around animal meat, ultimately they will have to change. And I think that’s a good thing.”