‘Flashbacks’ (Image courtesy of Matilde Merli)

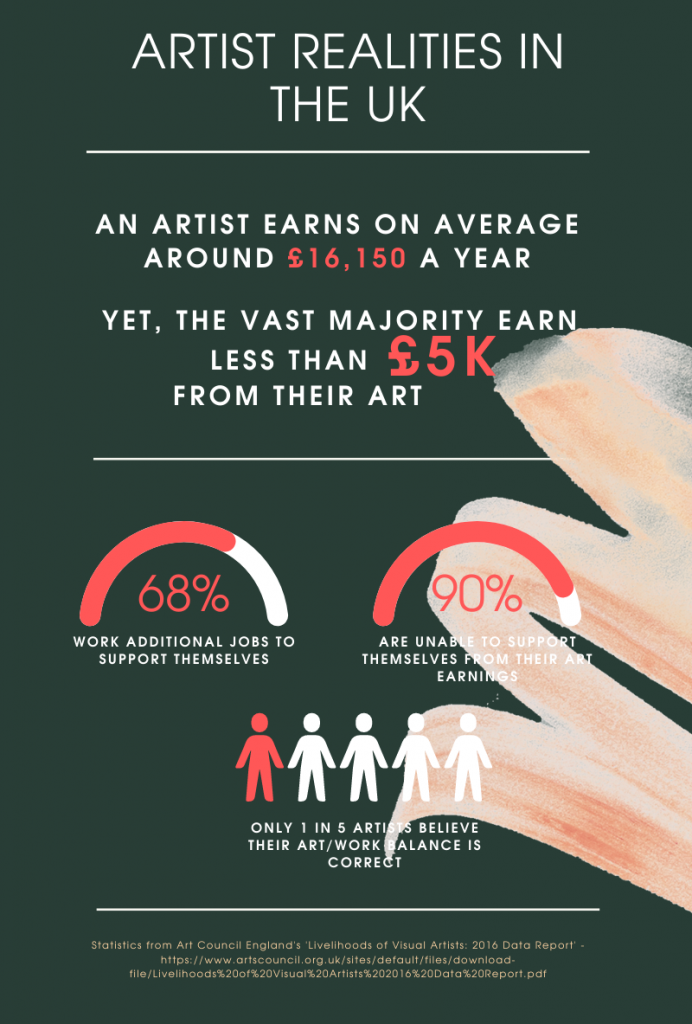

Over 80,000 artistic jobs have been lost over the course of the pandemic, highlighting a historical trend of inequality and instability within the art world. As the art industry begins to rebuild itself, what do UK artists think needs to change?

Artist Matilde Merli continued to create, despite the world closing down around her. Feelings of anxiety and confusion manifested themselves into luminescent creatures which sprawled across the pages of her sketchbook.

She wanted to make art for a living. Yet, the impenetrable art world she had strived to become a part of had disappeared nearly overnight.

“The pandemic was a difficult time,” said Merli. “All these thoughts I already had in my mind became huge. Staying in the studio and that space by myself and creating things every day, every hour was like therapy, understanding what I want to give shape to. The darkness inside, you know.”

Merli, 26, is just one of the thousands of UK artists who were attempting to make a living within the art industry when the pandemic hit. Over the course of the following year, she saw inequalities in the art industry become more apparent than ever and like many others, she thinks things need to change.

Attempting to sell art alongside studying a Visual Art Illustration degree at the University of Westminster, Matilde was in desperate need of better financial support. Like many other young artists, she had previously managed to stay afloat through working hospitality jobs on the side. However, when the pandemic hit, this extra source of income disappeared. It is estimated that more than a quarter of workers under 25 were forced to leave their creative jobs, compared with 14% aged 25 and over, according to the Centre for Cultural Value.

A historic culture of temporary and freelance jobs is greatly to blame, as government funding and furlough completely sidestepped individuals in these roles. With early-career artists filling a great deal of these positions, they faced the full brunt of the industry shutdown.

“I think we need to have an extra regard for young artists,” Merli said. “They try their best, but they couldn’t really at the same time because it was just too difficult mentally. The main dream is to be a freelancer. The problem is, it is a hard job to progress with.”

Aware of this widespread issue, former director of the London Design Museum, Alice Black, set up the artist support network Art Ultra, aiming to platform and provide support to emerging artists. One of Black’s biggest concerns, however, is the impact the Covid-19 continues to have on diversity within the sector.

“Those who have been able to survive were those who have an established survival network, or they have the financial resources to support themselves,” said Black. “If you are an artist who doesn’t have a family with income that can help, they therefore have to find a job otherwise they have no means of livelihood. Therefore, they are not continuing to be an artist. That means the art world, which tends to already not be very diverse, is becoming even less diverse.”

Recent research supports Alice’s fears. In a study by Inc Arts, it was found that 51% of the industry’s Black, Asian and ethnically diverse workforce took up freelance roles. Data also showed that these individuals were also more likely to face redundancy during the pandemic over their white counterparts.

Artist Kemi Onabule faced the loss of assisting jobs and gallery exhibitions when the pandemic hit. Although she was successful in continuing to sell her art and adapt to a new way of working, the artist became increasingly aware of ongoing issues surrounding female artist representation and industry attitudes towards the art they produce.

“I think the pandemic did highlight a lot of stuff to me that I already felt, but it seemed so scarily real,” said Onabule. “I think it pointed out that it’s very trend-driven and I think that’s quite dangerous in terms of what it does to artists,” she said. “Especially young women, because I think young men’s careers can go on forever. For women it’s harder to sustain that energy and that interest. I’ve had men say all kinds of stuff to me about my work like, ‘Oh it’s very trendy, it’s very in’.”

These attitudes have long been present within the art galleries and particularly the global art market. Statistics from the US National Museum of Women in the Arts show that there is a 47.6% reduction for women’s art at auction. Representation in UK galleries is an ongoing issue, with a report from the Freelands foundation finding that only 35% of artists represented in UK commercial galleries were women.

Underrepresentation continues to affect other groups of people too. Creatives with disabilities are some of the least represented people in the industry with only 1% of artistic staff in the visual arts being disabled, according to a 2018 study by the Arts Council. Those from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds make up just 2.7% of the workforce in the art sector.

“A lot of places could benefit from learning about dealing with artists as people rather than as this kind of either as a commodity or something to be scared of,” said Onabule. “I think people should be represented for the work they make and not because of who they are.”

Onabule also believes the increased use of digital platforms to exhibit artworks during the pandemic has further contributed to dismissive attitudes towards art, and particularly women’s work. “I think there is a flippancy in the way that people engage with art maybe post-pandemic because it easily accessed,” she says. “It’s worth not allowing that to get too far and for women’s art especially not to be the currency of flippancy.”

Whilst the internet had initially aided the industry-wide issue of artist visibility, an explosion of artworks uploaded online during the pandemic has had the opposite effect for many artists. Black said, “Online has grown tremendously, and yes it has had a very positive impact, but its super busy. It’s like an ocean of content that all of a sudden has been released.”

For Merli whose main art practice involved painting and drawing, digitalizing her work was a completely new skill. Displaying her work online became a necessity to be able to reach audiences and

boost her chances of making some sales. Unable to gauge viewers’ reactions however, and constantly fighting to get seen, she found it hard to keep up the motivation to keep going.

“Sometimes you just need to wait, and the waiting makes you overthink that maybe it’s not worth it,” she said. “I would just start a new profile or a website and leave it halfway.”

Despite this, inventive use of social media has provided a glimpse of an alternative and fairer way in which the art market could work. The Artist Support Pledge, a project which uses the hashtag #artistsupportpledge on Instagram, grew into a global network and provided a new space for artists to sell their work when galleries closed their doors in March 2020. Created by artist Matthew Burrows MBE , the project has shown that different and more equitable art markets can successfully function.

“I’ve worked at many levels in the gallery system, so I’ve seen how it works and how it doesn’t work,” said Burrows. “It’s very hard not only to get into the marketplace, but then for that marketplace to actually kick in and start giving a return. There are so many blockages in the way for that happening and there are so many costs involved that by the time you get your cut of the sale, it’s about a third of what the actual market value is.”

The pledge asks artists to post their artworks under the hashtag and sell work for no more than £200. Once an artist reaches £1000 in sales, they commit to buying another seller’s work. Anyone is free to sell and buy work as part of the movement.

By providing a zero-cost and alternative economy, Burrows hopes to instil a “generous culture” within the art world. This involves allowing all artists to take control of their own sales, by avoiding large gallery commissions and taking a stand against a historical culture of hyper-competitiveness within the industry.

“The way we operate economically is just a theory, just a model that we have come up with,” he said. “It’s not a good one and it’s a long way from being the best one, and that’s been understood for centuries.”

The movement is an ecosystem that provides a little more freedom for artists, makers and buyers to survive and thrive, Burrows says.

As galleries and the art market returns to normal, Alice Black hopes these new practices and perspectives will instil a conscious effort from large art institutions to back underrepresented and early career artists going forward. “This is starting to permeate the world of art,” she said. “To say ‘how can we imagine a world that is a bit more equitable?’, rather than a tiny proportion making millions and millions, and the rest living without not even the living wage.”

I think as an institution you have a huge amount of power to bring new kinds of practices and people on board.”

Black continues to fight for change using her platform, Art Ultra. Over the last 12 months, she has promoted the work of numerous early-career artists, including Matilde Merli, through online campaigns and organising exhibitions in new and alternative locations. Merli was given the opportunity to undertake an artist residency at the exclusive Hari Hotel in Knightsbridge, London.

“During the pandemic it was great to have help from ArtUltra and be selected,” she said. “It was a great push as it was a very down moment in my life, so it’s great when someone finds you and wants to celebrate your work.

My advice would be to keep believing in yourself, even when everything is going downhill. Because somehow, I’m sure there are more people like Alice Black in the world.”