Engineering is considered to be one of the most prestigious careers in India. But what is the mental toll of emerging as India’s top engineer?

At 16, Rajat’s days began before dawn and ended long after sunset. His routine was a blur of endless lectures and relentless study sessions, with his notebooks overflowing with scribbled formulas and diagrams. Despite the fast pace, Rajat felt increasingly hollow. This was his life at PCP Sikar, a coaching centre in Rajasthan known for its intensive preparation for the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE), the gateway to the prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

“Fear of failure was the only thing that kept me going for 20 hours a day. That’s how long we were instructed to study. Our phones were taken away, and we weren’t allowed to leave campus,” Rajat says. This rigorous routine, shared by 300 classmates, was punctuated by the ever-present pressure from parents and societal expectations.

In India, engineering is more than just a career choice; it’s seen as a path to prestige and financial success. The country produces 1.5 million engineering graduates annually for its $3.9 trillion economy, contributing to over 25% of the world’s engineers. However, only 3% secure top tech jobs and nearly half of these graduates find no employment at all, forcing 80% into unrelated fields.

(Image credits: Freepik)

Despite these grim statistics, the coaching industry preparing the youth for engineering degrees thrives, enrolling about 40 million students nationwide. These students, aged 16 and above, endure gruelling schedules: starting their days at 4 AM, attending 8 hours of school, followed by 4 hours of JEE coaching, and bi-weekly exams where their scores are publicly ranked.

“Your worth is based on your marks,” says Rajat. “Teachers used to announce our marks loudly in class to humiliate us. We were not allowed to have any hobbies or interests, as they were all seen as distractions.” Rajat’s days were consumed by a pursuit he wasn’t even sure he wanted, driven by the dream of a distant future. “They treat students as less than humans. I sometimes wondered if I was even learning anything or just memorising lines and formulas. But Dad said this was the only way, and I couldn’t bear to let him down,” Rajat says.

Experts argue that parents and their expectations are also responsible for students being incredibly stressed to complete coaching. “Parents often impose their own aspirations on their children, expecting them to excel in highly competitive environments without considering the child’s interests or mental health,” says Dr. Saranya Swaminathan, a psychologist. “This immense pressure from parents contributes significantly to the stress and anxiety experienced by students.”

This pressure is a reality for numerous students across the country. Shahid, from Kerala, moved to Kochi to fulfill his parents’ dream of him becoming an engineer. However, the pressure soon overwhelmed him. A year into his coaching, he reached a breaking point. Coming from a modest background, his parents invested their entire savings and even took loans to ensure he could attend a reputable coaching centre in Kochi. The weight of their expectations was a constant burden. Initially, Shahid was determined to meet these expectations. He woke up at 5 AM every day, attended school, and then spent another four hours in JEE coaching classes. His weekends were no respite, filled with additional coaching sessions and practice tests.

I remember the day it all became too much handle, I couldn’t take it anymore.

Shahid, former JEE student

“It was after a particularly tough mock exam. I scored poorly, and my teacher berated me in front of the entire class. The humiliation was unbearable. That night, I felt an overwhelming sense of despair. I couldn’t see a way out.” Shahid’s breaking point came when he was unable to answer questions he once found simple. The constant stress had eroded his confidence and will to continue. “I wrote a letter to my parents, apologising for being a disappointment. I felt I had no other choice but to end my life. But at the last moment, I called my mom. She sensed something was wrong and immediately called my friends, who rushed to my place just in time.”

After his suicide attempt, Shahid spent weeks in the hospital. His parents were devastated but supportive. They decided to bring him back home and sought counselling for him. “The recovery process was slow. I had to rebuild my self-esteem and learn to cope with pressure in healthier ways. I realised that my life was worth more than an exam score,” he says. Shahid’s experience underscores the severe psychological toll of the JEE preparation process. The intense focus on coaching often comes at a significant cost to students’ mental health, as they equate their worth to the outcome of the exam and fear disappointing their parents.

Despite concerns raised by coaching institutes and even the police, who often reach out to parents about signs of depression in their children, lack of aptitude for the subject, or inability to live away from home, many parents remain resolute. However, their concerns are often met with resistance. A representative of a top coaching institute told Press Trust of India (PTI) that in 2023, they had reached out to over 50 parents, clearly stating that their child was not fit for the intense preparation and needed to be with them. They noted that at least 40 parents did not agree to take their child back home or withdraw from coaching. Others who heeded the advice withdrew their children from the coaching but shifted them to other institutes, highlighting the rigidity of the situation.

The pursuit of an IIT seat has become a high-stakes gamble for millions of Indian students. To afford the exorbitant coaching fees, often exceeding £3,000 per year, many parents resort to desperate measures, including taking out loans. “I’ve often had parents bring students to me who are stressed, distracted, and often anxious and depressed due to the pressure placed on them. Many parents spend a lot of money on coaching classes for their kids, but sometimes, even after spending so much, they don’t see the results they expect. They might think their child isn’t trying hard enough or isn’t working as hard as they should. When the child tries to talk to their parents about how they feel, they often aren’t listened to,” says Dr. Swaminathan, who has 20 years of experience counselling teens and young adults in Chennai. This immense burden, coupled with the relentless pressure to succeed, has created a toxic environment that is pushing young minds to the brink.

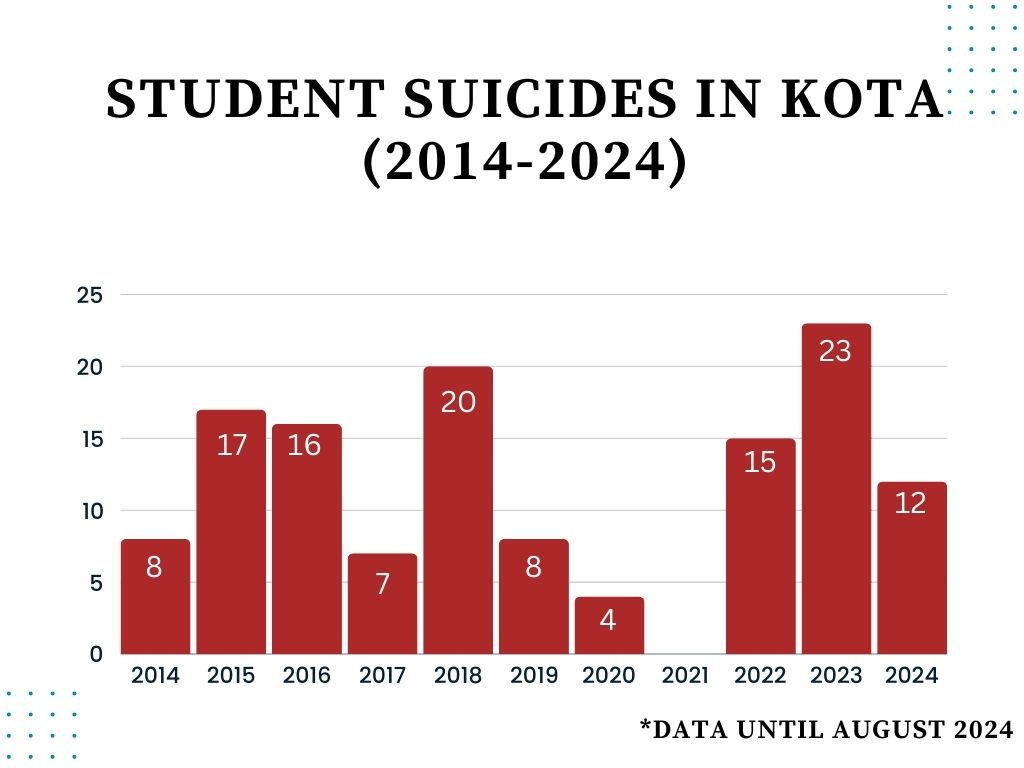

Kota, Rajasthan, a hub for JEE coaching, has become synonymous with a tragic trend: the alarming rate of student suicides. This year alone, 12 students have taken their own lives, the most recent incident occurring on 4 July 2024, when a 16-year-old student ended his life at a coaching institute in Kota. In 2023, an average of three students per month died by suicide, totalling 27 deaths. Between 2015 and 2023, the city witnessed 113 suicides among JEE aspirants. These stark statistics underscore the devastating impact of this hyper-competitive atmosphere. “The intense pressure of preparation, along with high parental expectations, peer pressure, and the inability to cope with the rigorous academic environment, are primary factors contributing to these tragedies,” says Dr. Swaminathan.

Kota’s tragic statistics reveal the dark side of this competitive environment, yet many parents still believe that enduring such intense pressure is a necessary sacrifice for future success. Satish Kumar, a parent and engineer, has enrolled his 16-year-old daughter in a two-year JEE coaching program at Allen Institute, Kota. He believes that intense coaching is necessary for a secure future: “If they struggle now, they will be happy and successful later. Hundreds of children get into IITs every year. With hard work now, they can live peacefully later as IIT graduates.” However, this perspective is far from reality.

The suicide crisis among students extends beyond coaching institutes. Even prestigious institutions like the IITs have been grappling with a similar problem. Between 2018 and 2023, an alarming 98 students at IITs died by suicide. “The truth is that even after completing these coaching classes, there’s no guarantee that students will be happy and satisfied,” says Dr. Swaminathan. “It’s a matter of shame that even India’s top institutes fail when it comes to ensuring student safety. IITs harbour some of the brightest minds in the country. Without ensuring student well-being, the very foundations of these institutes are at risk.”

IIT Madras in Chennai stands as a grim example of this issue. With a student population of approximately 10,000, the institute has been criticised for its inadequate counselling services, relying on just three full-time counsellors. Despite efforts to provide psychological support and recreational activities, the suicide rate remains stubbornly high, highlighting the urgent need for more comprehensive interventions. Dr. Ananya Mukherjee, a sociologist specialising in education policy trends in India, says, “India’s educational landscape has undergone a dramatic transformation. Once focused on nurturing well-rounded engineers, the system is now hyper-focused on producing toppers for competitive exams like the JEE.”

This relentless focus on rankings and competitive success has serious repercussions on students’ mental health. Dr. Anjali Verma, a mental well-being counsellor at Sunshine Coaching Centre in Kota, says, “The pressure-cooker environment of coaching institutes is dangerous to students’ mental health. They are constantly compared to their peers, leading to a sense of inadequacy and fear of failure.” The consequences are dire. The suicide rates among JEE aspirants, particularly in coaching hubs like Kota, are alarming. This tragic reality is a stark indictment of a system that prioritises ranks over human lives. “We are creating a generation of anxious, depressed young people,” says Dr. Verma. “The overemphasis on rote learning and standardised tests has stifled creativity and critical thinking. While there is growing awareness of the issue, support systems remain inadequate. Students feel isolated and overwhelmed,” she says.

So what is the way forward? “A fundamental shift in perspective is non-negotiable,” says Dr. Swaminathan. “Education should be about fostering curiosity, critical thinking, and a lifelong love for learning, not just about cracking exams. The government has a crucial role to play in this transformation. By regulating the coaching industry and promoting mental health awareness, it can create a more equitable and supportive learning environment” she adds.

In response to the troubling surge in student suicides linked to coaching centres in Kota, new measures are being implemented to address this critical issue. All wardens and staff members of hostels will now undergo professional training in management, and psychological, and behavioural counselling. This initiative aims to equip them with the skills needed to better support students and identify early signs of stress and depression. Mittal, a local education administrator, emphasised the urgency of this training, stating, “Desperate times call for desperate measures. This has been long overdue. Hostels often employ staff who are not trained to handle the complexities of students’ mental health. These courses will ensure that staff are professionally equipped to deal with students and monitor early signs of distress.”

In addition to the training, the city police have launched the “Darwaze Pe Dastak” (Knock on Door) campaign, urging mess workers and tiffin providers to report any signs of student absences or skipped meals. This initiative is designed to spot potential issues early and provide timely intervention. The administration has also mandated the installation of anti-hanging devices in hostel fans. This device, introduced by the Kota Hostel Association in 2017 but only recently enforced, expands if an object weighing more than 20 kg is hung from the fan, setting off a siren and preventing suicide attempts. Furthermore, “anti-suicide nets” are being installed on hostel balconies and lobbies to prevent students from taking extreme measures.

The Kota police are actively involved in these efforts, collaborating with wardens, mess workers, and tiffin service providers to detect and report signs of depression or stress. The Ministry of Education has introduced draft guidelines known as Understand, Motivate, Manage, Empathise, Empower, Develop (UMMEED) to enhance support for students. These guidelines focus on understanding the transitions students face and emphasise the importance of sensitivity and empathy. Psychologists like Dr. Swaminathan, welcome these measures: “It’s crucial that we create an environment where students feel supported and understood. The new guidelines and training programs are steps in the right direction, but continued vigilance and improvement are necessary.”

Image credits: Freepik

In addition, Kota’s “Student Cell,” established by the local police, plays a proactive role. The cell includes a control room that handles helpline calls, conducts random hostel checks, and provides counselling. “The cell is designed to be a resource for students to reach out when they feel overwhelmed,” says Kota Assistant Superintendent of Police Chandrasheel Thakur. “We visit hostels daily, interact with students, and ensure they know they can seek help without fear.”

Despite these efforts, the challenge remains significant. The district administration has emphasized that compliance with safety guidelines is mandatory. Recently, in February 2024 a hostel was seized for lacking anti-suicide devices after a student’s death, underscoring the administration’s commitment to enforcing safety measures. Dr. Anjali Verma, with her experience working in the frying pan of Kota urges broader systemic change: “While these measures are a step forward, we need a fundamental shift in how we approach education and student well-being. The focus should be on nurturing curiosity and critical thinking rather than solely preparing for exams. The entire ecosystem—parents, schools, and society—needs to work together to reduce the toxic pressure students face.”

Yet, amid these grim realities, there is a glimmer of hope. Rajat, who once felt crushed under the weight of relentless expectations, now speaks with a renewed sense of optimism. “I see things changing, even if it is slow,” he says. “Students are starting to speak up about their mental health, and there’s more awareness now than when I was at my lowest. It gives me hope that education will become healthy again—where learning is about curiosity and growth, not just exams and ranks.” His words resonate as a reminder that change, while gradual, is possible. “I believe there is a future where students like me won’t have to go through this,” Rajat adds.