Chinese embalmers are using Douyin to show their daily work. Will this quiet visibility finally reduce the stigma around deathcare?

In China, where most people grow up avoiding death, some embalmers are quietly showing it with colour, care, and a new sense of purpose. It starts with a lipstick. A careful dab on pale lips. A precise brushstroke above the eyes. In a quiet funeral home in Sichuan, 24-year-old Wang Nan, who shares her work online under the name “Tangmu Tanze,” describes how she transformed the face of a deceased grandmother. In our interview, she recalls the moment as one of the most meaningful in her career: “A peaceful farewell is also a kind of beauty.”

Wang, like a growing number of Chinese funeral workers, uses Douyin to show what deathcare really looks like. These are not stunts. They are everyday acts of public storytelling.

Wang says she often encounters awkward silences or judgment when people find out what she does for a living. “I just want people to know this job is like any other,” she says. “We just happen to work with those who can no longer speak.”

Yang Yucheng, a 32-year-old embalmer at a state-owned funeral home in Hangzhou who has worked for 11 years, recalls that when he first started, some relatives wouldn’t sit next to him at dinner. “They thought being near me would bring bad luck,” he says. “But over time, that changed.”

Three embalmers are bringing their work to Douyin, turning back-room routines into public knowledge and, in the process, testing whether quiet visibility can soften stigma and build trust.

For many embalmers, posting videos is not about fame; it’s about reclaiming space in a culture that prefers them invisible.

The funeral profession in China has long been treated as taboo in public discourse. Associated with death, it carries layers of cultural taboo and misunderstanding. Families sometimes discourage students from pursuing the major, and some practitioners avoid discussing their job publicly.

As Wang says, even her parents once questioned her career choice. “My mom cried, and my dad got furious. But I told them, “I want to see what death looks like.”

On Douyin, Binggan often wears a black polo shirt as he walks viewers through the craft behind the work. One video might focus on applying foundation to bruised skin; another shows the fine stitching used to repair facial wounds. He also uses these clips to debunk common myths, like the belief that an open mouth means unfinished business. “It’s just muscle relaxation,” he says. “We study pathology; we know anatomy. It’s not spooky—it’s skilled, delicate work.”

Binggan sees himself not as a messenger of death but as someone offering comfort to the living. For him, the most meaningful part of the job is helping families make peace with loss. “Sometimes people carry guilt for years over small things,” he says. “But a quiet farewell can ease that pain. That’s why I do what I do.”

Their videos are quiet by design. No music drops or shock edits, just a folded shroud, a final brushstroke, and a moment of stillness. “Makeup is a bridge,” Wang says. “It connects the living to the memory of the dead.” To Binggan, death is not an ending, but “a curtain call,” a final act to be witnessed with care.

In effect, they are building a visual vocabulary for dignity, reshaping how the public sees deathcare. In one clip, Wang uses theatrical makeup techniques to reconstruct the torn face of someone who died in an accident, delicately recreating features the family would recognise. “This is not about hiding wounds,” she says. “It’s about restoring a person’s memory.”

In contrast, Yang Yucheng says he focuses not just on the face but on the feeling. “When I finish, I step back and ask: Does it look like they’re resting? “Does it look like they’re at home?” he says. “I want the family to feel like their loved one is safe and at peace.”

But for Wang Nan, the internet doesn’t always reward subtlety. “Not everyone wants to see us on their feed,” she says. “Some call us unlucky. Some leave rude comments. But if one person watches and changes their view, it’s worth it.”

She’s no longer alone. On Douyin, a growing number of creators now share behind-the-scenes stories from across the funeral world, from coffin makers and crematory operators to hearse drivers. Some attract thousands of followers; others remain in the shadows. But together, they are quietly reshaping public attitudes and challenging professional stigma, one video at a time.

These Douyin creators are not chasing fame or profit. Their posts resist trends; they offer not hype but quiet proof of work, a way of saying, “We exist,” in a culture that often prefers them unseen.

“I don’t need applause,” says Binggan. “I just want our work to be seen.” Wang says, “I never thought anyone would care. But when someone writes, ‘I showed this to my mom,’ or ‘I’m not afraid anymore,’ that’s enough to keep going.”

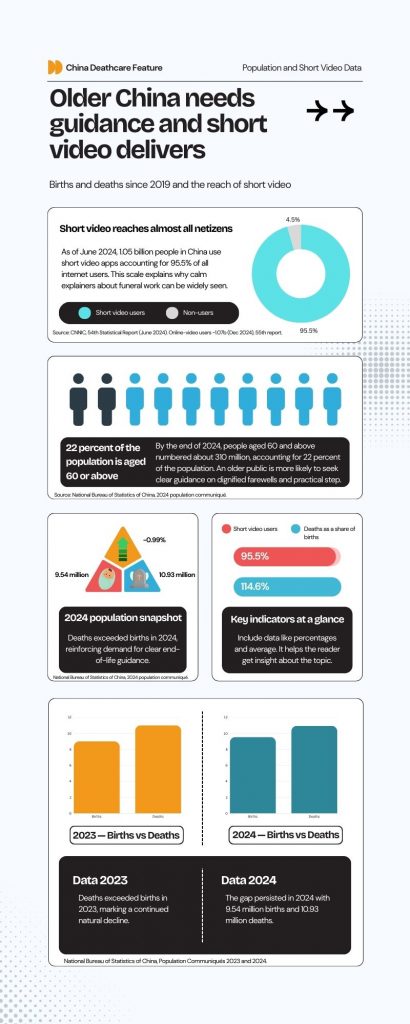

These stories reflect a broader shift among China’s younger generation, who are turning to social media to challenge taboos around deathcare. On Douyin, short explainer clips about day-to-day funeral work regularly draw large audiences, especially around Qingming, according to recent coverage by state and national outlets.

Recent reporting shows that a new generation of funeral workers in China are breaking a long-held silence and explaining their craft in public. A Beijing Review feature in April 2025 describes undergraduates in modern funeral management and notes that short social-media videos about day-to-day funeral work “regularly attract millions of views,” reflecting a wider shift toward openness. A 2024 feature by Sixth Tone likewise documents practitioners confronting prejudice and making their work legible to the public.

But not everyone approves of this new openness. Many state-run funeral homes still impose strict media controls, and some workers have been told to remove their posts. Wang keeps backup copies of her most emotional videos just in case.

Yang says he’s careful about what he uploads. “Sometimes I film a whole day’s work and then decide not to post it,” he says. “I don’t want to get my colleagues into trouble.”

The comments beneath their videos reveal how deeply the content resonates. “I always thought funerals were cold,” one viewer wrote. “But this message made me cry.” “I didn’t know people like you existed,” another said. “Now I’m not so afraid.”

Research on online mourning in China helps explain the shift. Individual remarks can accumulate into shared ways of talking about loss, and respectful explainers make end-of-life topics easier to discuss. Analysts also describe “continuing bonds,” where people address the deceased and each other, which helps with grief and often prompts practical questions in comments or direct messages.

Some followers reach out for guidance on how to talk to children about death or what to wear to a funeral. One young man messaged Wang: “My grandma just passed away. Your video helped me look at her without fear.”

In response, Wang posted a quiet video about memory and makeup, explaining how foundation can soften bruises, and a touch of lip tint can restore warmth to the face. “It’s not a disguise,” she says. “It’s restoration.”

Training remains limited relative to demand. As of early 2025, only nine higher vocational colleges nationwide offered funeral-service programmes, graduating about 1,000 students a year against roughly 10,000 vacancies at funeral homes; in 2024, a new undergraduate programme at China Civil Affairs University drew unexpectedly high entrance scores.

Around Qingming, civil affairs bureaus in multiple cities have hosted public activities—from collective sea-burial ceremonies to green-funeral briefings that bring the language of dignity into public space. In Dalian alone, about 17,000 people chose sea burials from 2012 to March 2025, according to official reports, and organisers say attendance has built year by year.

Cultural change often begins with being seen. Research on short-video platforms shows that repeatable, template-driven posts can create publics of imitation that make unfamiliar work legible and slowly shift what feels acceptable. Audience studies find that the visual, first-person style of Douyin helps people understand and feel with a subject even when clips don’t go viral; the effect is cumulative, not explosive.

Analyses of online memorial threads in China show how many small, respectful posts add up to shared norms for talking about loss. This helps explain why some readers move from an emotional reaction to practical questions about what to do and how to say goodbye.

For Wang and Binggan, the reward isn’t likes or followers; it’s trust. “I feel proud when families ask for me by name,” says Wang. “It means they believe I’ll do my best.”

Each clip, from the gentle combing of fringe to the closing of eyelids, offers the public not just a glimpse of technique, but a lesson in how to part with dignity.

As public trust grows, embalmers like Yang Yucheng have also noticed a shift. “Some families come to the funeral home asking for me by name because they saw my videos,” he says. “That’s when I realised I wasn’t just doing a job. They trusted me.”

For embalmers like Yang Yucheng, Douyin offers something his workplace cannot: visibility. “When I’m working behind hospital curtains, no one knows what I do,” he says. “But online, people see the care. They see the human part.”

Their techniques are not just cosmetic. Embalmers often perform facial reconstruction, camouflage, and mortuary makeup to restore dignity to the deceased. “We see all kinds of injuries, accidents, surgeries, and illnesses,” says Yang. “Our job is to make sure the family can look at their loved one and feel peace, not shock.”

These details rarely make it into public knowledge. But on Douyin, short clips quietly reveal the patience and skill required to prepare a face that has been burned, disfigured, or decomposed. “We want families to feel comfort, not fear. We’re restoring peace to the living,” Wang says.

Behind the screen, these creators carry more than brushes and cameras; they carry grief that isn’t always their own. The work asks for technical skill and steady empathy, and many describe the hardest part as helping families look without fear and leave with peace.

Institutions are also adjusting. New programmes now train students not only in restoration and ritual, but in how to communicate with the public. One newly established civil affairs university has even built a dedicated digital-memorial training hall where students practice speaking about remembrance in careful, respectful ways.

Not everyone welcomes the shift. Some workplaces keep strict media policies, and several creators told me they sometimes record a full day and then choose not to post. The caution is deliberate: they want to avoid harming families or breaking workplace rules.

That is why, in many videos, full names and faces never appear. The lens sits with gestures, hands brushing cheeks, tools being cleaned, and garments gently arranged so viewers see care rather than shock.

This restraint is part of the strength of the work. By choosing what to show and what to hold back, creators remind viewers that ethics and empathy can live on screen. The point is not to be dramatic; it is to keep dignity at the centre.

Initiatives like these point to a deeper shift not only in how embalmers are seen but also in how grief is talked about in public. In classrooms and comment sections alike, the silence around death is being gently broken.

“We work in silence, but people feel it,” says Yang Yucheng. “If someone watches and cries, they’re not crying alone anymore. That’s the quietest kind of connection and maybe the strongest.”

“Some people used to think we were dirty, unlucky, even cursed,” says Yang, who has worked in funeral homes for over a decade. “But on Douyin, when they see us, not as shadows but as skilled hands, as people with care and respect, they start to rethink.”

For him, that is the quiet power of the screen. “Social media won’t erase prejudice overnight,” he says. “But with every video, we reclaim a little dignity. We show what this work truly is.”