The Welsh-Yemeni community is one of the country’s oldest diaspora groups, with a contribution that stretches over a century, not least in war-time. However, how has a lack of acknowledgement and government immigration policy made their sacrifices feel unappreciated?

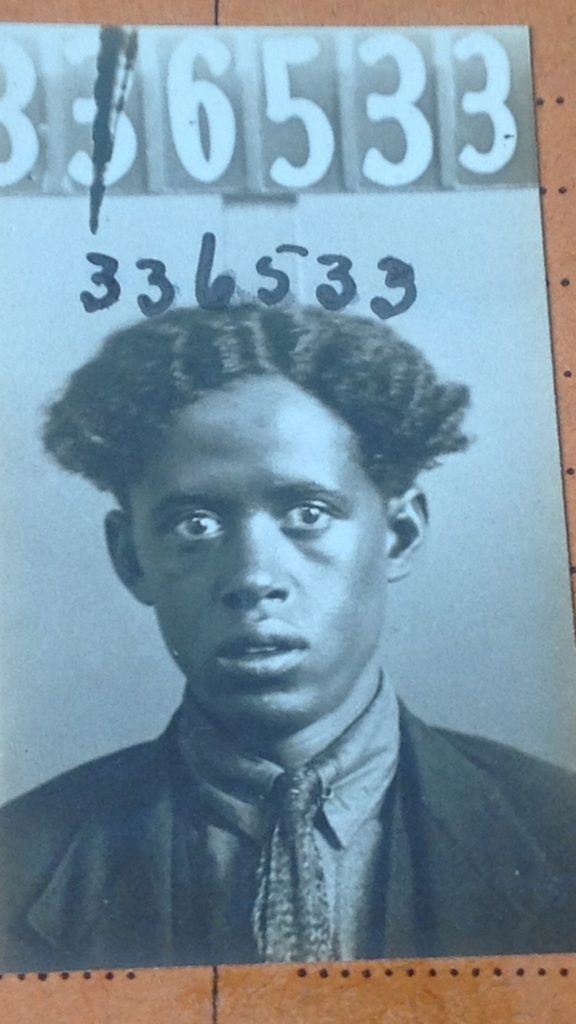

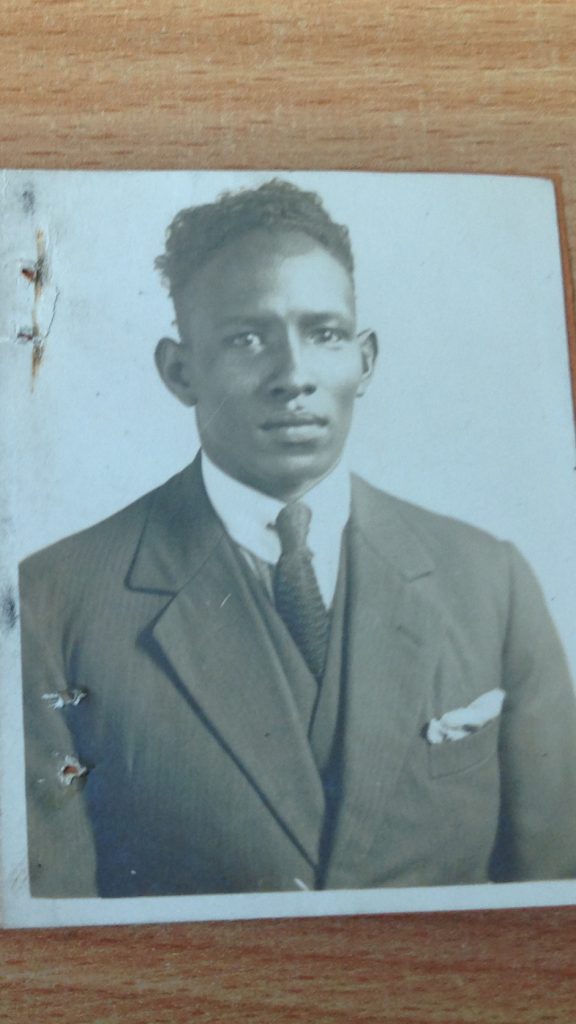

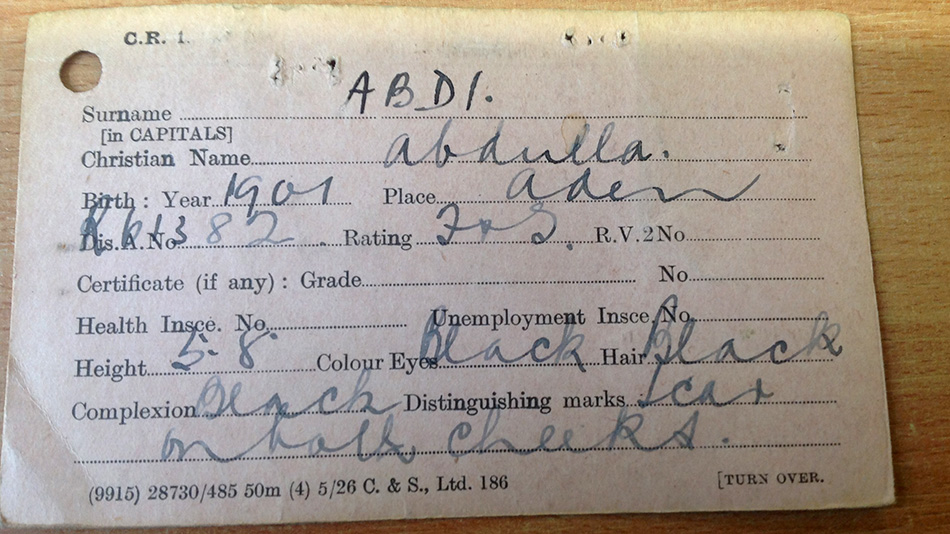

The black and white pictures of east African and Arabic men sat proudly was only the start of the story. Accompanying identity cards, just as weathered by time, detailed name, height, place of origin and physical features. The collection of dogeared pictures and handwritten identity cards displayed the start of a new community’s story in Britain.

Mohamed Yusef, a Somali-Cardiff resident, gathered thousands of pictures and identity cards, some over 100 years old, of Yemeni and Somalian seamen as they stepped off ships into British ports. For two years he sieved through each piece creating a one-stop window into two of the oldest Islamic communities in the UK, with the aim of educating Yemenis and Somalians, both here in Britain and in their countries of origin.

He sees that people should learn more about their ancestors: “how they lived, how they worked, what kind of work they were doing and how they survived during the time they were here,” says Mohamed.

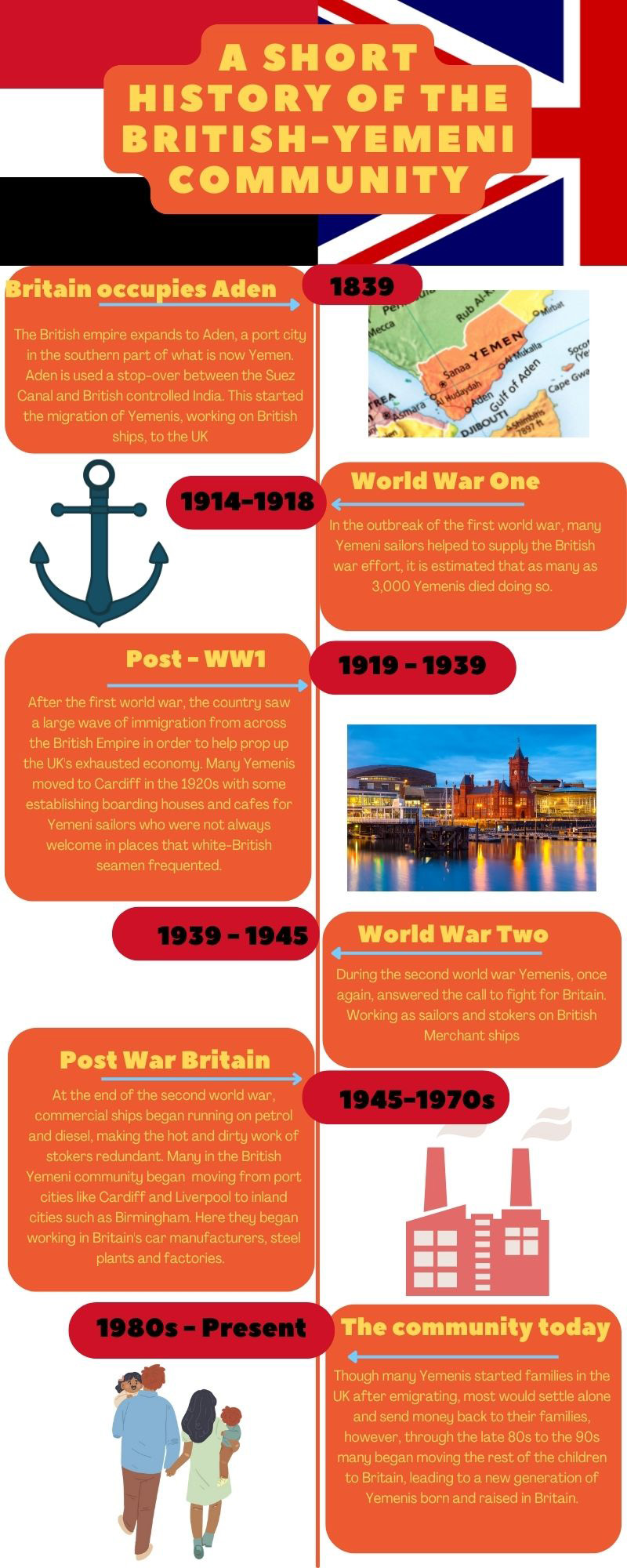

The British-Yemeni story started when Queen Victoria made the port of Aden, in southern Yemen, her first addition to the empire. The port served as a stopover between the Suez Canal and Britain’s imperial jewel: India. From Aden Yemenis would serve as stokers and sailors, transporting resources to and from Britain, fueling the country and its colonial territories. After arriving in the UK many would step off and live in port cities like Cardiff, Swansea, and South Shields.

This seafaring tradition would carry on through Britain’s darkest days. When the UK found itself at war, the Yemeni community stepped up. During WW1 and WW2, they served on merchant ships sending supplies to fighting troops, many were lost at sea. In south Shields one of the oldest and largest communities, 800 Yemeni men died during WW2.

Daoud Salaman is a second-generation Yemeni-Welshman, and previous chairman of the South Wales Islamic Centre, he says, “we had some members of the community who had been torpedoed two or three times. And they still got up and went back to sea carrying on just as it was just part of the job, they got killed.”

Daoud’s father had suffered also in his journey to reach Britain, after a sandstorm killed his family in Yemen, the nine-year-old boy trekked hundreds of miles to reach Aden. Years later he would establish the Cairo Café, a cultural landmark of Cardiff Bay.

During the Falklands war in 1982 many Yemenis worked on ships ferrying troops across the south Atlantic during the conflict with Argentina. Daoud was working as a marine engineer onboard the Uganda ferrying equipment and soldiers to the Falkland Islands.

Though he very much downplays his part during the Falklands conflict, he believes the British-Yemeni community is yet to see much recognition for their sacrifices during both world wars, “they were not acknowledged for their part in the war… they were disregarded, they weren’t regarded as part of the [Welsh] community. And yet they paid a big part in the [Welsh] community,” he says.

According to Daoud a small plaque stands in Barry Town Hall listing the men from the area that were lost at sea. However, many feel efforts to remember their role in Britain’s wars are rather scarce. Some feel that the Welsh government has not done enough to recognise those migrant communities who lost young men in Britain’s war efforts.

Mohamed says, “the people who give their blood to the UK as a seaman, as people who fought for this country and the Queen , there’s no recognition taught… should the assembly give recognition to those people who, as seamen, fought for the country during the World War One or Two.”

“All you want to have is a kind of sense of belonging to one another, that recognises and is able to understand the histories that brought us here.”

Dr Abdul Azim Ahmed

He feels that a simple memorial paying gratitude to their service would be a worthwhile contribution.

However, some feel that recognition for Yemeni, Somalian and other diaspora community contributions to Welsh society should run deeper than a memorial or government show of appreciation.

Dr Abdul Azim Ahmed is the secretary general of the Muslim Council of Wales and the deputy director of The Centre for The Study of Islam in the UK, at Cardiff University.

“The government could put up a plaque somewhere or put up a statue or add a certain day of the year or something… but that doesn’t really make a difference,” says Azim. “All you want to have is a kind of sense of belonging to one another, that recognises and is able to understand the histories that brought us here.”

Azim feels that building a stronger sense of community organising is a better way of showing appreciation for historical contributions and building a stronger sense of togetherness in Wales and Britain. He sees the way to achieve this is through local community and national groups such as the Cardiff Yemeni Community Association (CYCA) and the MCW.

“There’s this kind of communal project we’re working on together, which is the well-being of our communities, and our ability to be safe and flourish and have dignity and security and stability. I think these are all much more important than anything government led,” says Azim.

However, one area where the government has undeniable control over is immigration and visa policy.

The British government has come under heavy scrutiny after the then-home secretary, Priti Patel, unveiled a plan to send some asylum seekers on a one-way flight to Rwanda, a scheme which has so far stalled amidst a series of legal battles.

Azim describes this policy as aggressive but points out that the process as a whole for people trying to navigate the British immigration and visa process is already incredibly difficult. As someone from a Pakistani and Bangladeshi background, Abdul and his siblings have already been through transferring his mother’s leave to remain status into a biometric card, though she has been in the UK for a number of decades.

“It was absolutely the most complex, difficult thing I’ve ever gone through in my life to try and get this card for my mum,” he continues. And that’s with the advantage of five of us with different levels of context and relationships with composite institutions.

“We as a Yemenis, we sacrificed for this country, and we made some of the history you know, and we become part of the story

Khaled Alshameri

“It took so much effort between the five of us to navigate the system just to get a card… if you don’t have the advantage of, you know, British kids who can manage this process. How will you even manage, how are you meant to go through this?” Says Azim.

Members of the British British-Yemeni community have also spoken of the difficulties navigating British immigration and visa processes. However, since the start of Yemen’s civil war in 2015, opportunities to simply visit family members here in the UK have been made even more complicated with limited travel corridors and massive inflation making travelling to Britain a heavily costly effort.

Khaled Alshameri is the vice-chairman of the CYCA, he says, “we wish we can bring some of our families here, just for a visit, because it’s really difficult for us to go back there, and with the regulations now, with the home office, there’s a lot of conditions which are impossible for them to make it.”

Khaled moved to the UK in 2012 and has only seen his parents once since emigrating, his children are still yet to meet his family in Yemen. He feels that the Yemeni contribution to Britain as well as the community’s long history in the country should bring some leniency in the UK entry process. Especially when members of the community are still alive today who remember the sacrifices made.

“They still remember… their father, who stepped out of that door and never returned, and some of them they still remember their fathers when they come back from factories with stained hands,” says Khaled.

“We came here a long time ago, and we became part of this country, some of the Yemenis they went for in the World War Two, and they never returned,” says Khaled “… if they could make it easier for those people who already here and for people who wants to come and visit the families.”

“We as a Yemenis, we sacrificed for this country, and we made some of the history you know, and we become part of the story. So, if we go like special treatment, especially in this situation, like bringing our families here,” Khaled says.

For those refugees looking to make the UK their home, the steps to being accepted can be long and arduous. According to The Guardian, asylum seekers from war-torn countries such as Yemen and Syria have been told that it is safe to return to their home countries, despite the obvious dangers in doing so. The immigration and visa process can also be highly costly, with no guarantee of success at the end.

Azim believes the entire process of entering the UK, under any status, is a huge challenge. “It’s not just migration of, say, family, with British citizenship, or with the right to remain even, it can just be for holidays, it can just be for visits, it can be temporary…it’s expensive. It’s confusing. It’s complicated,” he says.

Despite this, Azim does not believe that historical contributions should mean differential treatment when it comes to immigration policies. He believes that it creates a pre-requisite for migrants seeking to find a home in Britain, “it does kind of reinforce this idea of the good migrant, the good immigrant, the one who’s earned his citizenship,” says Azim. “I think something like that would only reinforce this idea, which is, you know, the few, the right… the deserving few.”

He instead believes that the system itself needs to concentrate on the concepts of community building, “I think what we need is a radical overhaul of how we think of belonging and identity in the first place,” Azim says. “Humanity has a right to live on earth in different places to seek out community and flourishing wherever that needs to take place.”

However, as Government restrictions on those who can and cannot enter the UK continue to provide challenges for those in the Yemeni community, as well as others, many feel that the historic contribution given in peace and war time continue to be overlooked.

Despite this Mohamed feels it is still just as important for young generations to understand their history with Wales and their country of origin. For now, the data base lies in a USB stick on his desk, after an IT issue took the website offline, still looking for a web-designer to assist him, he is as determined as ever to bring it back to life.

While Mohamed feels that government and public recognition is important for Yemeni and Somalian ancestry, he hopes the aged black and white pictures will allow the youth to see how their grandfathers started two of Wales’s oldest and established communities.

Mohamed says, “it is educational, for the young generation … to know more about their ancestors who live here in Wales, what they are doing, and how they live and how they contributed economically, and culturally, among the other communities around here.”