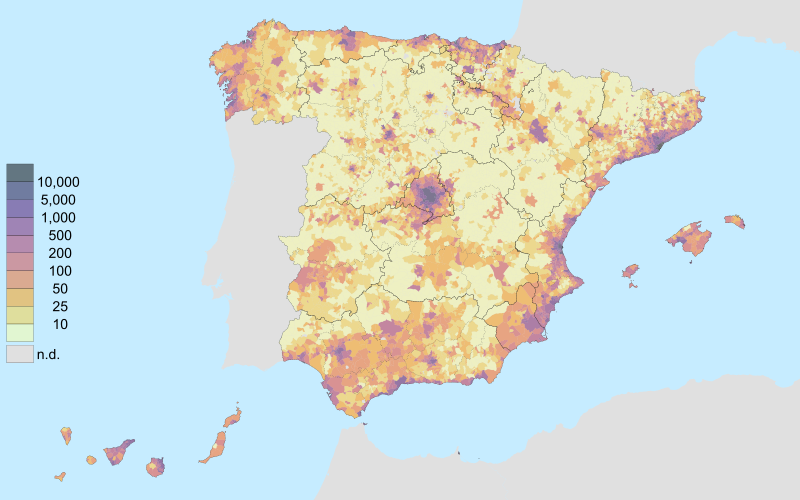

Five regions in Spain now make up over half of the country’s territory but only 5% of its residents. What are the main problems associated with rural depopulation?

Every summer I spend two fantastic and relaxing weeks in my Spanish grandmother’s village of birth, Castrillo de Don Juan, which is located in the province of Palencia in Castilla Y León.

With a swimming pool, goalposts, bars, long walks across beautiful landscapes of sunflowers and vegetable patches, it is the perfect place to disconnect for a fortnight.

The highlight of this fortnight spent in the village is the weekend of annual August festivities, when around 500 people come from all over the country to spend 3 days and nights at the birthplace of their parents, grandparents or great-grandparents.

Events in these festivities include the inter-village football tournament, a paella served for several hundred villagers and 3 successive nights of music, dancing, and fun.

Yet, if the village during this high point has 500 or so people, and a vibrant atmosphere, during the winter months the situation is quite the opposite.

Between 50-100 people live there and, over the last few years, the sole shop, doctor’s surgery, and school have all been forced to shut down.

Aside from weekly visits from fruit and meat sellers, and the daily bread run, very little comes in and out of the village.

Rural depopulation has thus hit this village, like so many across “Empty Spain”, hard.

Although Castrillo is not completely empty during the cold winter months, the ongoing problems associated with rural depopulation means, at its worst, that thousands of Spanish villages like my own could become less and less populated until they are reduced to virtually nothingness.

Valareña, a village with a population of around 285 in the autonomous community of Aragón, is in a similar although slightly healthier position than Castrillo, in part due to the prominent role that its women play.

And the experiences of its residents typifies many of the day to day struggles which living in small villages in both Aragón and Castilla Y León entail.

“When the antenna does not work, we are totally disconnected, the lack of mobile signal means we can’t use our phones, nor the internet, nor wi-fi, not even our landline. I remember being totally disconnected like this for over a week,” states Paola Biota, one of its residents.

“And it enrages us to see them cut back our rights and services little by little so that the village disappears,” she adds.

The lack of technological investment in Castilla Y León and Aragón is one of the main factors which has stimulated, or at least exacerbated, the recent trend of rural depopulation.

This is a point made by Soria ¡Ya!, a campaigning group founded in 2001 to spread awareness of the problems which exist in both the city and province of Soria, in Castilla Y León.

“It is not just about having internet or wi-fi of a high standard, but also having phone signal. There are many parts of the province which don’t even have mobile coverage,” says Vanesa Garcia, its spokesperson.

“In terms of telecommunications, with the current situation of the pandemic we have realised how important they are,” she continues.

Between 2010 and 2017, as reported in national newspaperEl País, 62% of all small villages and towns lost population.

And, as research for this project, I asked 100 people from across the country several questions. One of those was the main challenges for rural Spain and, as can be seen below, several of them emerged.

Indeed, a point made by campaigning groups such as Soria ¡Ya! is that the lack of investment in technology is by no means the only issue which has driven these trends of rural depopulation.

“Throughout the 19 years that Soria ¡Ya! has been active, many of our protests and points of contention are still the same today,” states Vanesa Garcia.

“Infrastructure, the hospital, healthcare, formation, attracting businesses to the area. They are all the same,” she adds.

When asked what measures they wanted the government to take, the respondents of the survey did not hold back.

Nonetheless, the last few years have witnessed, spurred on by Sergio Del Molino’s 2016 academic work Empty Spain, an upsurge in political attention to this increasingly urgent problem.

On the 31 March 2019 Soria ¡Ya! joined more 100,000 people from 20 provinces and 100 political associations in protesting as part of the “revolt of Empty Spain”.

“We do consider action towards climate change, women’s role, education, food and resources as necessary. But also, we want basic services,” states Vanesa Garcia.

“For everything we have to travel many miles. There is little safety in villages because they closed the quarters of the Civil Guards. This all amounts to people not wanting to come and live in the villages, and the few that are here logically want to leave,” she explains.

For Paola Biota, back in Valareña, a village with a population of 285 (it has decreased by 50 since 2010), she argues that a crucial factor in this is the lack of services, which has led many families to migrate to nearby Ejea de los Caballeros, a town with a population of over 16,000.

Located just 15 kilometres away, Ejea de los Caballeros is an example of an important trend in the changing Spanish landscape: the growth of larger towns which, at the same time, exacerbates the demise of smaller villages.

Indeed, Aranda de Duero in Burgos, Castilla y León and around a 40 minutes drive from my family’s own village, now has a population of 32,000, yet as late as 1970 its population numbered 17,000.

Aranda de Duero’s reputation in producing and selling wine, as well as its summer Sonorama Ribera festival, which in recent years has counted on performances from British artists Noel Gallagher and The Vaccines, as well as some of Spain’s well-known artists including Amaral, IZAL and Amaia Romero, have contributed to its increase in population.

The rise of urban towns and cities has meant that the inhabitants of small villages, and especially women, have in some cases little choice but to abandon them in search for work, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crash.

And according to The Financial Times, the Spanish economy could also be the most affected by the Coronavirus pandemic, potentially further exacerbating trends of rural depopulation.

As it stands, the residents of rural Spain believe that the future of rural Spain is at a crossroads.

Economic issues apart, one of the most important factors behind rural depopulation is linked to education.

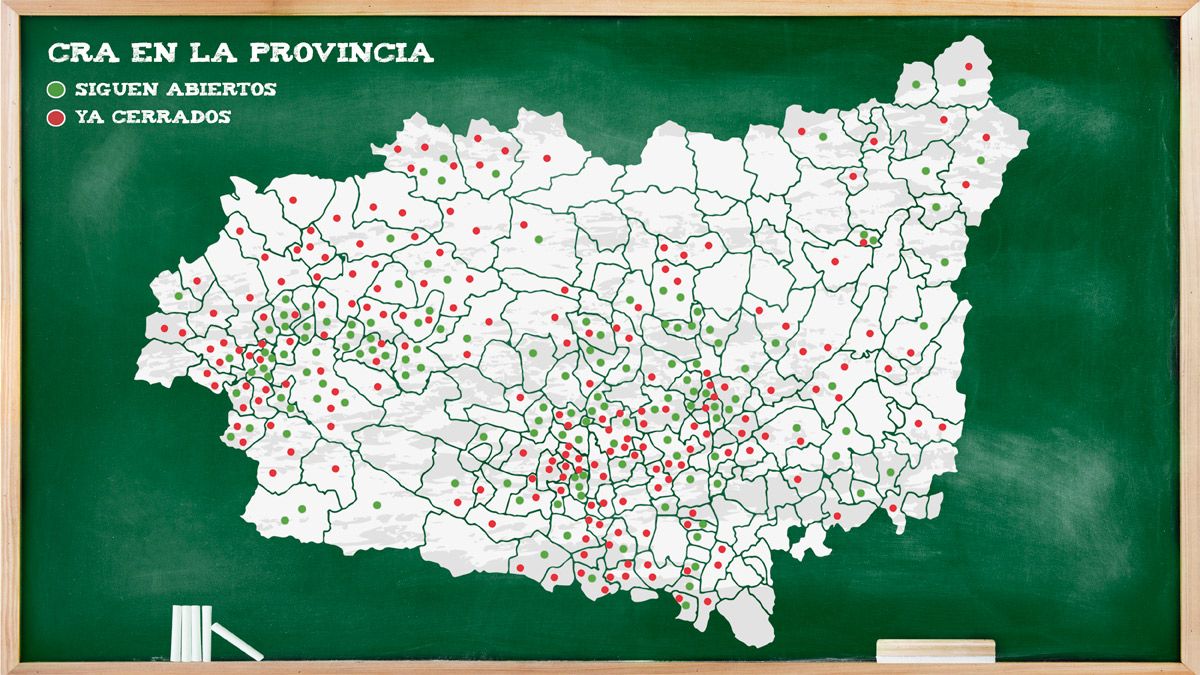

“When a school shuts, a village receives its death sentence,” remarked Jordi Marin, a Chemistry and Physics teacher, to national radio station Cadena Ser.

Indeed, a school closure in a rural village in Castilla Y León or Aragón is not just an unfortunate incident or an inconvenience to a few, isolated people.

A village cannot sustain itself without children, and children cannot be sustained without education.

A school being forced to shut down due to financial problems, a lack of children in the area, or difficulties in finding suitable teaching arrangements, as is regularly the case throughout rural Spain, can spell the beginning of the end of that village’s prospects.

In the province of León, as reported in La Nueva Cronica, almost 200 rural schools have shut down since 1991.

Paola Biota, in Valareña, is one of many to have gone to school in their rural village and thus well equipped to talk about her experience.

“Studying in my village was good, but slowly by slowly the school is getting empty. There is a low birth rate and the school is increasingly with less children; it has come close to shutting several times,” Paola explains.

One factor behind this is the lack of resources upon which rural schools can count upon.

“We count on less resources and not as good infrastructure as in urban cities and bigger villages. The resources we do count on is few and far between and generally older,” Paola states.

“In terms of extracurricular activity, we have no choice but to travel two or three times a week to Ejea de los Caballeros for that,” she adds.

In spite of the problems associated with school closures and resources, Paola Biota states that she had an education which was happy and of a high standard.

“Despite doing university degrees and getting through school, like everyone else, they call us stupid and uncultured because of our accent or way of speaking,” she claims.

An El Diario.es article in 2019 about the previous PISA tests suggested that, when comparing children of the same socio-economic background, a better education was imparted in rural schools than in their urban counterparts.

“Because there are so few pupils, we are all in the same class, and there is just one teacher for everyone…this can also be an advantage, since we are treated more personally and there is greater unity between us all,” Paola explains.

“The ability to have your school 5 minutes away from your home is something we really like,” she adds.

But problems in rural education go much deeper than villages laying claim to primary and secondary schools.

Even in the occasions where young people such as Paola get to study in their local village, university graduates tend to, as reported in El País move to bigger cities such as Madrid or Barcelona for work-opportunities.

If education is one of the main problems which exarcebates rural depopulation, then healthcare is another.

“We want the modernisation and amplification of the Santa Barbara hospital,” argues Vanesa Garcia.

“We currently have to travel to places like Valladolid or Burgos (an hour or two drive away) if we want certain specialist treatment,” she adds.

To this end, the shortage of doctors is a clear sticking point.

Castilla-La Mancha, another autonomous community within Empty Spain, counts on 395 doctors per 100,000 people, which is 81 less than the country’s average.

One of the main problems associated with rural health is the lack of young doctors who practice in Castilla Y León, as the data chart highlights below.

Although health, education and investment in technology are 3 of the main causes for rural depopulation, they are not the only ones.

“The biggest challenge of today and in the future is to avoid depopulation. There isn’t a magical formula which can solve it, there are many circumstances which all need to come together,” states Vanesa Garcia.

Part of the circumstances which Vanesa Garcia would like to come together include policies aimed at addressing inequality and supporting entrepreneurial women.

“We are hopeful that the future of Empty Spain is very positive and finally we can solve the inequalities that still exist,” she states.

Despite the problems associated with rural depopulation, residents are also keen to extol some of its benefits.

And, despite the rise of small towns, urbanisation, school closures and problems with health centres, not everyone has left their village, as Paola is keen to demonstrate.

“I have been lucky enough to find work in my village, meaning I can stay here. Ever since I was little I always wanted to live here,” she says.

“I am very proud of my village. I have the best memories of my life here and I hope to make many more to come. It’s my land. My roots. My people. The place where I have developed, not just physically but as a person too,” she adds.