By 2050 climate change could see a 90 percent decline in puffin numbers, what hope is there to ensure that future generations can enjoy these boisterous little fishermen?

Between the months of April and August every year, a selection of small isolated rocks dotted around the North Atlantic transform into a haven of life, where vast swathes of seabirds return to land to breed.

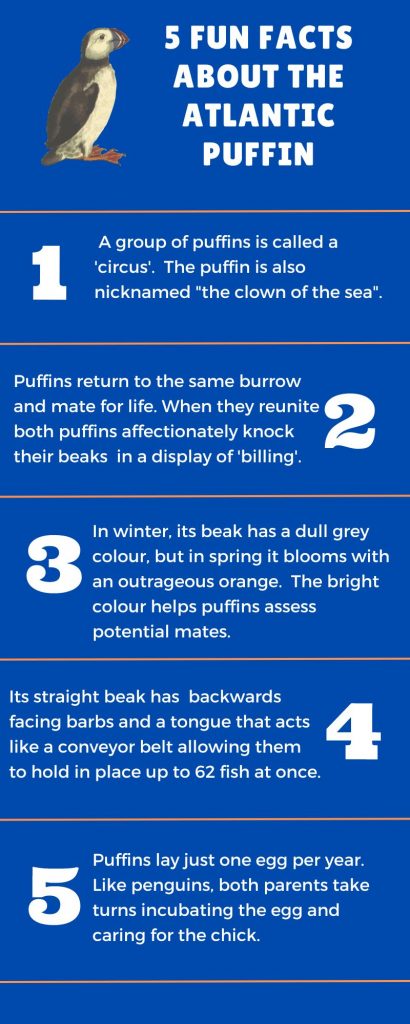

Here is where you can find the Atlantic puffin, a plump pint-sized black and white seabird, most easily recognised by its striking orange beak.

The puffin prioritises life at sea over land, typically spending over seven months of the year away from its colony. When it returns to breed, it spends most of its time on the water fishing for itself and its chick known as a ‘puffling’.

Its iconic beak boasting shades of orange, grey and cream, is lined by denticles, little spiny barbs that face toward its throat that hold its catch in place. Its tongue acts as a conveyor belt pushing the fish towards the back of the beak allowing them to carry up to 62 eels at once.

This bounty of eels appears like a silver moustache contrasted by the bird’s bright orange beak making it a favourite shot for wildlife photographers as they return home after a day at sea.

“During breeding season you often see them hurrying about trying to get the sand eels into their burrows before they’re mobbed by the black gulls or other scavengers,” said Elliot Hook, a wildlife photographer who has worked extensively with the puffins of Skomer Island in west Wales.

“You’ll see them come in to land with a beak full of eels but then abort and do a fly around to ensure the coast is clear, often landing instead a good distance from the burrow and then darting over to it on foot.”

Sand eels are critical to marine food webs and are the puffins preferred food source, but they have been growing in scarcity which has forced puffins to compete with other birds. This is part of a much broader picture that paints a painful reality of the human impact on the fragile ecosystems of the ocean.

Dr. Rob Thomas, is a Cardiff university academic and an expert on zoology and seabird behaviour.

“Birds such as gulls and skuas steal fish from the puffins as they come back to land, but the extent that this happens depends on their own food supply,” he said.

“These scavenger birds often linger at the back of fishing trawlers picking off discards, when fishing regulations are changed by the UK or EU governments, this challenges their supply which leads to them stealing food from puffins or preying directly on sand eels.”

Th puffins being forced to run the gauntlet by these scavengers as they return to their burrows is symptomatic of a much broader and more worrying trend.

“The main issue is that our oceans are warming at an alarming rate due to climate change, affecting marine conditions and causing a change in the distribution of sand eels,” said Dr. Thomas.

“These are a vital part of the puffin’s food supply and they are very sensitive and affected hugely by sea temperatures.”

Rising sea temperatures are the single biggest threat to the puffin that is a result of human activity but it is not the only one. Much like the birds stealing their eels, we too are encroaching upon their food supply adding even more of a strain.

“People are harvesting sand eels on an industrial scale and are competing directly with puffins,” said Dr. Thomas. “We use them for fish meal or as protein for animal feed and even as fertilizer for agriculture.”

“One obvious move would be to end the sand eel fishing industry but this has both human and economic implications so it’s easier said than done,” he said.

Earlier this year the government launched a consultation process hoping to ban sand eel fishing, something that has been pushed by the Royal Society of Protection of Birds (RSPB) for quite some time. The potential ban was described as ‘game-changing’ by the RSPB’s head of marine policy, Helen McLachlan.

“Our seabirds have declined in the face of increasing threats from climate change and other human activity,” she said. “A ban on industrial sand eel fishing could be the single greatest thing decision-makers can do to throw our seabirds a lifeline.”

The changes and declines in eel patterns and quantity have had immediate negative impacts on puffin numbers with colonies sometimes failing to raise any young due to the absence of available food sources.

The shortage of sand eels can even result in colonies collapsing entirely and forcing the puffins into changing their migration and breeding patterns due to their need for an abundant source to be nearby.

In some instances in order to survive, puffins have been forced to switch from sand eels to less nutritional alternatives such as shrimp, molluscs, or marine worms which is something that has been studied in great detail thanks to a citizen science project initiated by the RSBP.

The group launched Project Puffin in May 2017 in order to gather information about how the puffin’s diet has been affected by climate change. The project uses images of puffins returning to land captured by photographers and wildlife lovers at colonies around the UK to try and understand the current ecological situation.

“This is a citizen science program nicknamed ‘Puffarazzi’” joked Dr. Thomas. “People love to take photos of puffins coming into colonies and as a result, you can actually monitor what fish they are eating,” he said.

“The RSPB has been using these photos to measure the proportion of sand eels to other less preferred prey and then use this data to try to calculate the impact that climate change is having on eel numbers,” he explained.

Wide-ranging and robust data is key in understanding the effects, problems, and potential future solutions against the challenges facing the puffin.

Data gained from the annual puffin census provides crucial insight into how the populations at various colonies around the UK are doing on a year-by-year basis.

Whilst numbers globally are declining, some colonies in the UK have seen increases of about ten per cent annually.

“In Skomer almost every year we are seeing record breaking numbers, but it’s important to remember that these may be inflated by birds that are migrating from other colonies that are really struggling,” said Dr. Thomas.

“It’s a mixed picture really because globally puffins are in decline but yet you go to Skomer and you see these vast numbers of them which hides all these threats going on in the background,” he said.

A recent example of puffin success that could be implemented in some of the UK’s struggling colonies was in Eastern Egg Rock in Maine. The Audubon Society, an American non-profit dedicated to bird conservation, used a combination of puffin transplanting, mirrors, and wooden decoys to grow a colony on the island that had been extinct for over 70 years.

The team transplanted puffin eggs from Newfoundland to Maine. With the help of these decoys, recorded puffin calls and fish deliveries, a successful colony developed over time with there now being about 200 pairs of puffins recorded to be breeding there.

“Really we should be doing whatever we can to protect these magnificent birds, they are one of these iconic species that everyone recognises and loves,” said Dr. Thomas.

The threat posed by climate change means that future generations may never get to see this famous seabird renowned for its charm and personality if the stark predictions for a 90% decline prove to be accurate.

“You don’t get puffin haters, they’re one of these universally adored animals that everyone can and should get on board with in terms of conservation.”

“The British Isles are a crucial part of global seabird ecology and diversity and they are the jewel in the crown of what we have here that is truly precious and important, we have a global responsibility to do our bit to protect them.”