After years of being edged out of the LGBTQIA+ community, this is what bi activists are doing to break away from the stereotypical binaries of lesbians and gays and finding space for themselves.

In the scorching heat of July in 2009, Lois* Shearing was at an Alice Cooper concert in Brighton with their best friend, when the words “I think I like girls too” were uttered out of their mouth. But the feeling of absolute joy and relief was only short-lived, and one that Lois wouldn’t feel for years to come.

It all changed when Lois had a first-hand experience of how queer people treated the term ‘bisexuality, which means attraction beyond gender. At the age of 16, their first girlfriend said that Lois’ bisexuality made them “too straight for gay people, and too gay for straight people”. While this marked the end of their relationship, the words stayed in Lois’ mind.

“I was being made to feel like an interloper in queer spaces,” says Lois, a bisexual activist and author. “It’s like you don’t really belong anywhere. It’s almost gaslighting. This is my lived experience, this is my reality, and everyone around me is saying no, it’s not. It constantly wears you down.”

This is an experience that a lot of bisexuals can relate to. Almost half of bi people tend to avoid LGBTQIA+ events as they are treated unfairly in those spaces due to stigma around their identities and toxic misconceptions, as per a Stonewall report from 2020.

They are prone to double discrimination – discrimination from the heterosexual community and LGBTQIA+ community – in various settings, which Lois suggests results in poor mental health outcomes.

The rejection of bisexuals and the stigma surrounding the label makes it difficult for them to navigate their identity and feel a sense of belonging in their local LGBTQIA+ communities.

“You’re having to desperately cling on to your own reality and perceived sense of self, while people around you try and weigh you down,” says Lois. It’s been more than a decade since they came out but they still have to justify their presence in LGBTQIA+ venues. “It does put you off from accessing queer spaces.”

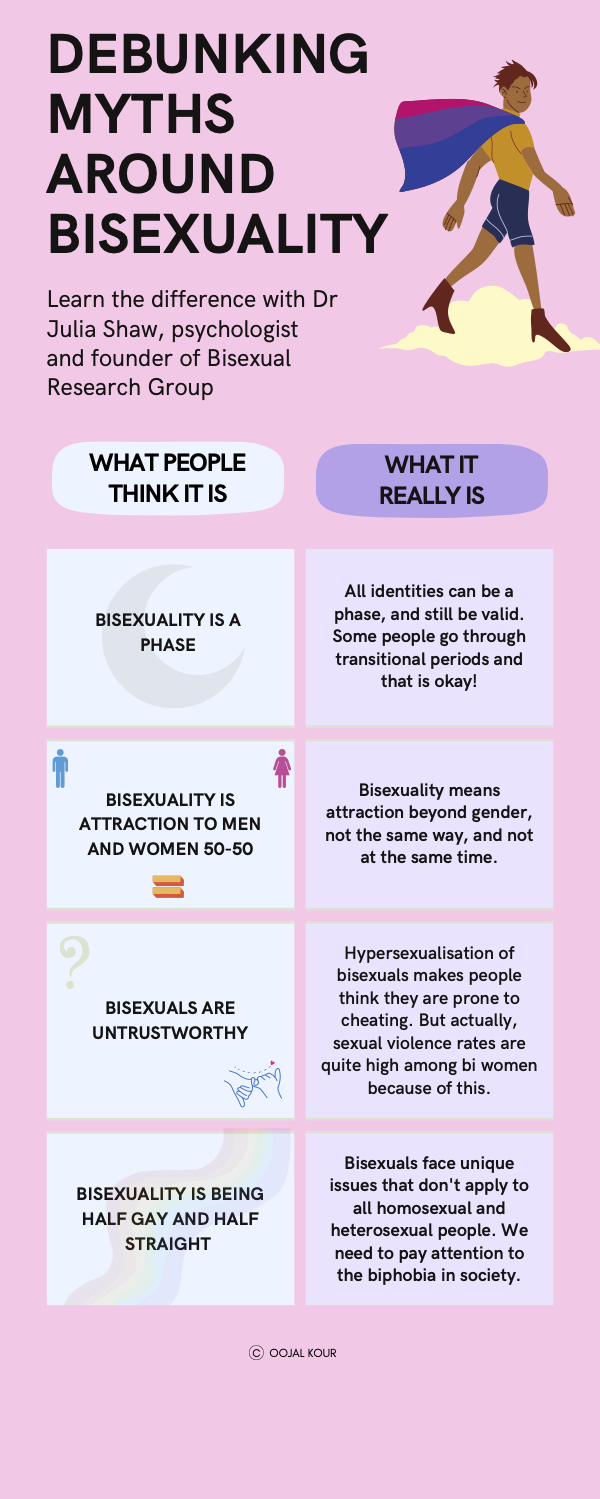

Almost two-thirds of bi people battle with depression, with one in ten engaging in self-harm due to the harassment they face in their day-to-day life, Stonewall reports. The negative stereotypes associated with bisexuality are an underlying factor for this, according to Dr Julia Shaw, psychological scientist, and founder of Bisexual Research Group.

My brain would constantly tell me that you can’t be bisexual. We are erased so often, it’s reflected at you.

Vaneet Mehta, bisexual activist

“Bisexual people are often rendered invisible,” says Dr Shaw. “Society has quite a lot of biphobia which presents bisexuality as not a real option. It’s seen as a stepping stone to gay, as a phase. As these things permeate popular culture, it means that people are less likely to come out.”

Disassociating from bisexuals has been a political move in the past, according to Dr Shaw. The nuances of bisexuality were seen as ‘too complicated’ in the fight for queer rights, which led activists to discard the identity altogether rather than accommodate it.

“Politically, there have been times when it’s been strategically a better idea to just say people are either 100% gay or straight because it’s the in-between, the bi, that makes it less stable,” she says. “And if your sexual identity is seen as less stable, then it doesn’t need protection.”

Many bi activists on the frontlines of the LGBTQIA+ civil rights struggle were thus pressured to identify as gay or lesbian. Dr Shaw argues that this led to bi-erasure, when in fact bisexual activists were part of queer liberation movements from the start, with activists like Brenda Howard who organised the first Pride marches, and Lani Ka’ahumanu whose incessant campaigning led to the addition of the B in LGBT.

Misconceptions around bisexuality have continued to the present times. Libby Baxter-Williams was 13 when she came out as a lesbian but later realised that she was bisexual. While she was fully accepted as a lesbian by her friends, they stopped associating with her when she came out to them as bisexual.

“My gay friends abandoned me,” says Libby, director of Biscuit, a bi advocacy group. “None of them said that they were stepping away. My phone stopped ringing, I stopped getting asked to go out on a Friday night. Some of them said that I’d lied to them. I’ve got traumatic memories attached to it.”

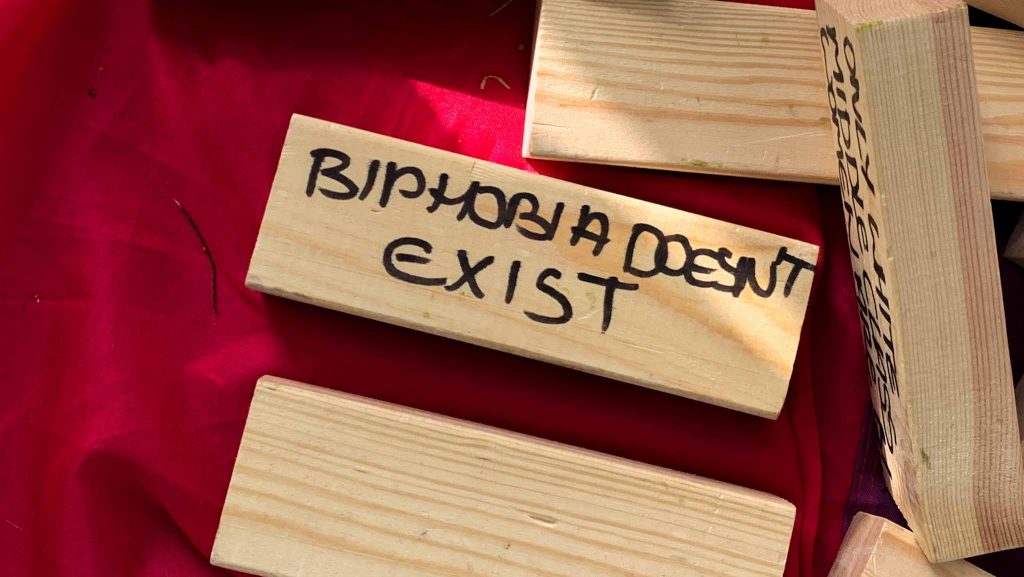

This deterred Libby from being on the wider gay scene and talking about her romantic life as people were often judgemental and hostile. “Biphobia is just so common in gay bars. They don’t like it if you talk about different gender partners,” she says. “That’s crazy. I am bi, I’m not going to deny a massive chunk of my personality and my lived experience because it makes you more comfortable.”

Another form of biphobia is hypersexualisation, which predominantly sees bisexual people as sexual objects, explains Dr Shaw. “For bisexual women there’s often the assumption, especially by heterosexual men, that bisexuality is performative. It’s this idea that everything a woman is doing with another woman is all for the men,” says Dr Shaw.

The increased rates of sexual violence in bisexuals stems from this very thought, she states. “When bisexual women make it clear that they are not interested in the heterosexual man, he is more likely to aggress against the two women because he sees this as a very sexual situation, even though it’s not for him,” she says.

Vaneet Mehta, a bisexual activist, believes that this is a type of monosexism, where people can only be attracted to one gender, which ultimately leads to bi-erasure. “It’s the idea that you are either straight or gay. There’s nothing in between, it’s just black and white, no shades of grey,” he says. “It happens so systemically that we erase ourselves.”

When Vaneet first discovered he was bisexual, the term was commonly associated with negative connotations of infidelity, STD transmitter, and unstable relationships. People around him made him feel like bisexuality was not a real thing, which made it difficult for him to sum up his feelings. Ultimately, he ended up internalising the idea of “picking one side”.

“I found it really difficult to come to terms with my identity because my brain would constantly tell me that you can’t be bisexual. We are erased so often, it’s reflected at you,” says Vaneet, who still harbours some form of internalised biphobia because of his past experiences.

“Now I’m in a relationship with a man, and sometimes I get thoughts running in my head like, what if I am actually just gay? How do I know I’m bisexual?”

To tackle this, Vaneet is trying to accept fluidity and understand that even if something does change in the future for him, it does not mean that bisexuality isn’t real. “It just means that I have learnt more about myself, and that’s okay,” he says.

What helped Libby through her internalised biphobia was meeting bisexual people who were ‘out and proud’ and embraced their bisexuality, without worrying if people thought they were the wrong type of homosexual. This encouraged Libby to embrace her bisexual identity, but it didn’t come easily. She says, “It took a lot of support from my family, my therapist, and this new community that I’d found.”

Another form of support can be through bi-specific groups that can help those who are not plugged into any other communities, according to Dr Shaw. She believes that being plugged into these buffers can give people an inclusive space within the LGBTQIA+ community that they might not find elsewhere.

“Having public conversations about bisexuality makes it much easier for people to accept their bisexual identities” says Dr Shaw. “Most of the time, bisexuality is still jumped over. When society keeps telling you that you’re not real, it really helps to have a counterbalance where you have a bi-affirmative community.”

Grassroots organisations are doing everything they can to help boost the bisexual community and fill the gap in resources, says Vaneet who believes that they are working endlessly with less to no funding.

“We’re limited by the resources, time, energy, and money that we have,” he says, adding that a lot of the time, these groups use their own money to try and get visibility. This is despite bi people making up the biggest LGBTQIA+ group.

This lack of funding and underrepresentation led bisexual groups to pull out of Pride in London and attend an alternative Bi Community Picnic instead. The picnic was held at Regent’s Park and was open to all bi+ people and allies.

According to Libby who organised this, it was a way for the bi community to get together without the pressure of being in large crowds or worrying about facing biphobia.

One of the attendees Mary had never been to a Pride event before. She says, “I have never been to Pride before because I felt like an imposter. I feel quite alone in my sexuality sometimes. Here, seeing flyers for different groups, like Bi Survivors Network, Bi Sewing group, I hadn’t envisaged having a social group where everyone’s bi.”

Creating spaces like these where people can come out safely can lead to tremendous positive psychological effects, says Dr Shaw. who encourages people to be their full selves and not deny their identity. “I totally underestimated the positive consequences of being out. I thought it was not going to change much. It changes it a lot actually. And it makes you feel more full, more authentic, more you.”

Growing up in a rural time with very few queer people, Lois felt the need to come out and be vocal about queerness at an early stage. Despite facing some setbacks, they are now able to feel a part of Pride due to the picnics, bi floats, and the community they have found, which has made the environment around queer spaces more welcoming.

Internally, it has been a slow journey of acceptance for Lois. “I have definitely gotten to the point where it doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks,” says Lois. “I know I deserve to be here. I know that this space is for me. And I think that’s just a point that I hope a lot of bi people reach eventually.”

*Lois uses they/them pronouns