Recruitment agencies in Nepal weave false hopes of better lives to thousands of workers who dream of going to the UK. But how do these agents manage to commit the perfect crime?

In the bustling streets of Thamel in Kathmandu, Anish was hopping from shops to offices, in hunt for a job that would be sufficient for his family. He had left his two months old pregnant wife back home in Surkhet, to look for any respectable jobs in the capital city. Anish never wanted to go abroad as he did not have enough money to take that risk but when recruiters in Nepal gave him no response, he had no other option left.

Going abroad was easier than staying back home, as there were posters and pamphlets of recruitment agencies all over Thamel. Anish went to an agent with no hopes of hearing back but, he was surprised at the response he received.

“When I went to an agent to enquire, I got a lot of information from him in just half an hour and it all seemed right. The agent advised me to apply for a seasonal worker in the UK as the money was good,” said Anish, who wasn’t aware of the false promises his agent was feeding him.

Anish Gurung, 32, from Surkhet, was told to arrange a hefty amount of money by his agent to stay and work in the UK.

He said: “They asked me to deposit £4000 and said all the money would go for my accommodation and food in the UK.”

“When I told them I didn’t have enough money, they gave me hopes of how I will be earning more than the said amount in only 2 months of going there.”

According to a report by Amnesty International, an NGO focused on human rights in the UK, many aspiring migrant workers in Nepal face barriers to accessing foreign job opportunities. They rely on private recruitment agencies to guide them through the complexities of overseas employment.

The report states: “Many are unfamiliar with their fundamental rights, and job descriptions and hence, they become dependent on recruitment agencies to navigate their journey in a foreign land.”

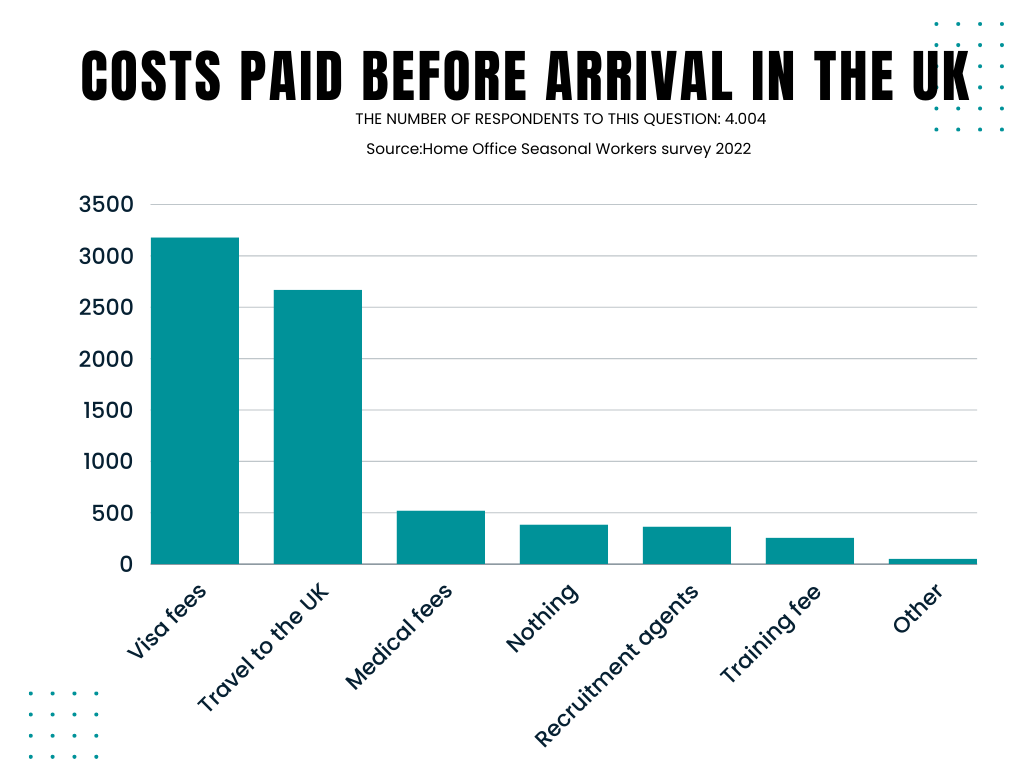

Numerous workers who were unaware of the rules were charged extra money in the name of application fees.

Anish said: “I was struggling financially at the time and had to borrow money from my neighbors at a high interest rate as banks in Nepal would not approve my loan.

“Banks would ask for collateral and I had nothing to offer.”

Anish had lost both his parents while he was a child in a tragic accident. Since then, Anish has been all on his own. He was a bright child growing up and had passed his Year 10 examinations under a government-funded scholarship.

“I did not have the luxury to take chances but somehow I managed to borrow the money and deposited it to my agents.”

“I only knew I was going to the UK and would be working on a fruit farm. My agency never disclosed the type of work I will be doing,” said Anish.

In November 2023, the House of Lords published a new report urging the government to take strong action on the abuse that seasonal workers face on British farms.

Following the report, UN experts raised serious concerns about the risk of exploitation of these workers on farms across the UK. They also commented on how migrant fruit pickers were burdened with debts even before they reached their destination.

After Anish received his visa, his agent sent him to a different company that dealt with the itinerary of these workers.

He said: “After my visa got approved, I, along with other workers was redirected to another company who asked for an additional £600 for our tickets.”

When he finally came to the UK after taking a huge amount of loan, he was sent to Newent in Gloucestershire where his employer explained his work to him.

Anish would be picking fruits on the farm for the next six months and would be in charge of packing up those fruits in boxes, hygienically.

“I thought the work wasn’t bad and as I had experience of working in fields back home, this wasn’t too much.”

“Everything was going well until I received my first pay. It was not even close to what I was told I would get by my agents,” he continued, “When I asked where my money went, I was told I had signed the contract which explained everything.”

Anish was made to sign the contract by his agents in Nepal who had gone silent after Anish went to the UK.

“I tried to make my managers understand but it was all there, on the paper! I did not check the documents before signing them as it was in the English language,” Anish said.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) found in their investigation that migrant workers were often deceived by third-party agents who reap the benefits of workers not being able to understand the English language.

The report published by the House of Lords to clamp down on the abuse of migrant workers encourages Gangmasters and the Labour Abuse Authority to consider workers not being charged fees beyond what is permitted by law. It also states that the agreement between the employee and employer should be in seasonal workers’ first language, and self-attested ahead of their arrival in the UK.

TBIJ in their another investigation in 2023 found out that some workers were being charged high illegal recruitment fees. The scammers and overseas staff of scheme operators often target people who are desperate to go to a foreign land.

Anish earned £1200 in the first month of coming to the UK. He explained how excited he was about this achievement but later realized that £400 would be deducted for his accommodation.

“Every night I dreamt of clearing up my debts and when I received my first pay, I was happy that it was going in the right direction until I was told that I would be charged for accommodation.”

“I had friends from Nepal working on the same farm who faced a similar issue. We had no clue that the money we deposited to our agents in Nepal were just illegal fees.”

“I still don’t know if I will be able to track them down,” he said.

The Horticultural Sector Committee published a report early this year that recommends a number of new measures to stop the exploitation of these migrant workers to some extent.

The report urges the Home Office to increase the budget for the GLAA, an investigative agency for labour exploitation in the UK so they could use the money to hire extra labour inspectors.

There are hundreds of men like Anish who have paid illegal fees to middlemen as there were no guides available for the workers to follow.

Anish described the work as comparatively easy. The poor living conditions he was living in did not even compare to what he was going through psychologically.

He said: “I had no issues with the workload. When I decided to come here, I knew I had to work hard, and I still have a huge debt which needs to be resolved so I did not care about my living status.”

“My friends would complain about our managers shouting at us, but I believe nothing comes easy in life so, I never rebelled.”

“Sometimes our superiors would throw racist remarks and laugh at us, but we all had bigger fishes to fry.”

Anish recalls how every night after work, his friends would make plans to make extra cash.

“We heard from some seniors that we could run to Portugal after our visa expires but for that, we would need to pay extra money.”

One of Anish’s friends, Bablu Haudey from Bardia in Nepal almost got duped while planning to flee to Portugal.

Bablu said: “Who doesn’t want to make extra money? My family had taken a huge loan for me to come to the UK and despite working here sincerely, I could not pay off the debt.”

“While applying for Portugal, I asked suggestions from people who previously left to work there and saved myself from getting duped again.”

Despite not making enough money, Bablu, a 25-year-old, would make the most out of his off days. He would not shy away from a pint with his friends from other countries.

“I often took pictures on the farm while working and I was good friends with my supervisor so sometimes, we all would go out to have beer during holidays.”

Bablu has gone back to Nepal now, but he cherishes the time he spent in the UK with his friends and roommates who taught him important life skills.

“The friends I made there were for life. We all cried and laughed together so I know it means a lot to me. The next time I meet them, I wish we are at least happy in life”, he said.

Workers like Anish and Bablu often embark on the path of working in a foreign land, unaware of the fact that they are entering a world of exploitation and deceit. These workers work tirelessly, away from their families, but debt follows them like a shadow everywhere they go.

Job centres in Nepal like Wide-Space International are organising events for workers who wish to work outside the country. They hold seminars and try to spread the word by providing accurate information on bridging the gap between migrant workers and employers.

A spokesperson for Wide-Space International said: “It’s sad to see recruitment agencies making money out of vulnerable people. As the people of Nepal heavily depend on foreign employment, the agencies should navigate the complexities of the process, providing guidance and support to workers which will enable workers to make informed decisions about their employment prospects abroad.”

“The recruitment system in Nepal preys on the desperation of individuals seeking employment and hence, they exploit this vulnerability by setting higher fees for recruitment.”

“We encourage people to do proper research before they make any decisions. Our agency prioritizes ethical recruitment practices, and our mission extends beyond mere profit-making. We offer hope for migrant workers seeking fair and dignified employment abroad.”

Meanwhile, Anish has gone back to Nepal after his visa expired and is now working with Nepali friends he made in the UK. He is starting his life from scratch and paying off his debts one pound at a time.

He said: “Despite the huge debt I have, I at least get to be with my family and enjoy a meal with them. I am working very hard, hoping to pay off what I owe but my villagers are kind as they sympathize with me and my situation.”

After going to Nepal, Anish tried to contact his agent and even visited his office, but his agent was nowhere to be found.

“They say the company is going to shut down as the recruiters in the UK canceled the contract with them after the reports of illegal fee came out.”

Anish has now opened a TikTok account which he uses along with his friends where he shares tips on going abroad. He debunks some of the questions and rumors about going to the UK and hopes that this step would at least save a life.

He said: “I want people to not repeat the same mistake that I did. Do your research and read every paper given by your agents. Even if you don’t understand the language, don’t be afraid to ask for help.”

“A lot of my friends in Nepal reach for TikTok to find answers and hence, I decided to answer questions there. I hope by doing this, I get to warn people about the dangerous debt bondage migrant workers often fall into, unknowingly.”

“While I was away, my wife, Sunita gave birth to a healthy baby boy, and I think this is God’s way of protecting me. I need nothing else from life.”

Anish and Sunita both have started working in a factory and are trying their best to pay off all their debts.