Virginity remains a deeply sensitive issue, shaped by ancient doctrines and evolving beliefs, as society wrestles with modern perspectives on purity, autonomy, and identity.

With people having strong opinions on a woman’s virginity, writing this piece was a tad-bit difficult for me. It’s like trying to negotiate a minefield while writing about virginity. The subject of virginity is saturated with stronger held beliefs, moral judgements, and individual experiences. I came across an array of viewpoints as I dug deeper into this complicated subject, all of which were equally valid and passionate.

I talked to many who dismissed the concept of staying a virgin till marriage as something from the past. For them, having sex is a natural way of expressing intimacy that is unrestricted by society or religion. They believe that a person’s value is unaffected by their sexual past. Some, on the other hand, view virginity as a commodity that increases a woman’s attractiveness to potential husbands. This viewpoint emphasizes how women are still objectified. Then there are some who see virginity as a holy promise, a representation of love and purity. They view it as a personal decision based on moral or religious beliefs. This position frequently collides with views regarding sexual health and STD prevention.

Being caught between these opposing viewpoints, I felt powerless by my fear of being judged. My objective as a writer is to deliver an educated and unbiased article, but how can I do so when the topic is so polarizing? If I were a virgin, would I be regarded as prudish? Or promiscuous if I wasn’t? Would my credibility be undermined by my personal experiences—or lack thereof? The truth is, there is no simple solution. Virginity is a complicated topic with no clear-cut right or wrong answer. It is an extremely private decision that ought to be honoured, regardless of one’s beliefs. But clearly, a woman’s virginity is not as private as it should be.

As I delved deeper into my research, attempting to unravel the tangled threads of these conflicting viewpoints, I found myself on a journey through time and across cultures. I sought to trace back the origins of these deeply ingrained expectations surrounding virginity. What I discovered was both fascinating and unsettling: the concept of virginity, particularly female virginity, has been inextricably linked with religious doctrines and cultural practices since time immemorial. From ancient texts to modern interpretations, religion has maintained a tight grasp on societal attitudes towards sexuality, especially women’s sexuality. This realization made me understand why the topic remains so contentious and emotionally charged even in our seemingly progressive times. It became clear that to truly comprehend the complexities surrounding virginity, one must first grapple with the profound and lasting impact of religious teachings on our collective consciousness.

The concepts of virginity and purity in Hinduism are complex and often rooted in ancient scriptures such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. In these texts, characters like Sita and Draupadi are central to the discourse on a woman’s purity and chastity, yet they present contrasting narratives around sexuality and virginity.

Sita, the central female character in the Ramayana, is often portrayed as the epitome of virtue, fidelity, and purity. Her unwavering devotion to her husband, Rama, is tested in numerous ways. After being rescued from Ravana, the demon king who had abducted her, Sita is asked by her husband Rama to prove her chastity to the kingdom. This leads to the infamous trial by fire, or Agni Pariksha, where Sita is made to walk through a path of fire to prove her purity. Despite emerging unscathed from the flames—a sign of her virtue and innocence—Sita is later exiled to the forest due to rumours and doubts from the people of the kingdom. In exile, she gives birth to Rama’s twin sons, further showcasing the burden placed upon her to constantly prove her purity and loyalty

On hearing this, Sita broke down. ‘My trials are not ended yet,’ she cried. ‘I thought with your victory all our troubles were at an end… ! So be it.’ She beckoned to Lakshmana and ordered, ‘Light a fire at once, on this very spot.’

-(from Valmiki, trans. R.K. Narayan)

Professor James Heagarty, who specializes in the studies of the Ramayana and Mahabharata in Cardiff University, explains, “The story of Sita illustrates not just a test of purity but a societal mechanism to control women’s bodies and their perceived honor. Sita’s ordeal is a manifestation of the male-dominated culture, where a woman’s worth is constantly scrutinized and measured against impossible standards.”

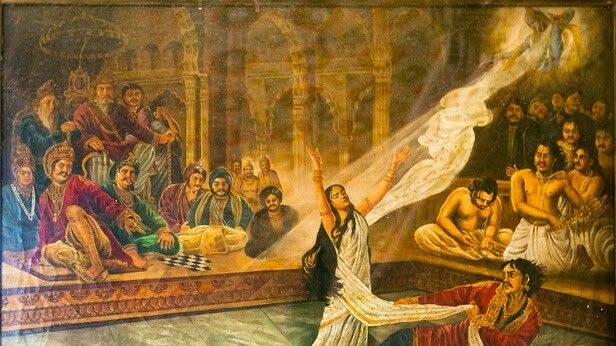

In contrast, Draupadi, a pivotal character in the Mahabharata, embodies a more complex narrative. Draupadi’s humiliation during the disrobing episode in the Kaurava court is one of the most significant events in the epic. After her husband Yudhishthira gambles her away, her brother-in-law Dushasana attempts to strip her in a court full of men, while her five husbands remain silent. Dushasana even calls her a prostitute, further degrading her in public. This act of violence and the subsequent inaction of her husbands lead to the great war of Mahabharata, as Draupadi vows for vengeance and justice.

James emphasizes, “The war in Mahabharata itself is a culmination of the societal disregard for a woman’s dignity and the patriarchal structures that allowed such public humiliation. Draupadi’s humiliation is not just a personal affront but a societal failure to protect a woman’s honour. These narratives around Sita and Draupadi play a crucial role in establishing the myth around virginity and highlight the dangers of defining a woman’s worth through her sexual history.”

The historical evolution of the concept of virginity in India is deeply intertwined with its religious and cultural heritage. In pre-colonial India, the idea of virginity was closely linked to the concept of purity and was often seen as a prerequisite for marriage, particularly in upper-caste Hindu societies. However, it’s important to note that India’s vast cultural diversity meant that attitudes towards virginity varied significantly across regions and communities. In this context, professor Simon Brodbeck from Cardiff University adds an interesting angle to the story. He adds, “The need to ensure the purity of women, especially brides, was historically linked to the patriarchal lineage system. Men wanted to pass their land and property to their male offspring, and marrying a virgin woman was a way to ensure paternity—knowing that the son was biologically theirs since a mother giving birth would naturally be the child’s biological mother.”

The arrival of colonial powers, particularly the British, brought new dimensions to the concept of virginity in India. Victorian moral codes, which emphasized sexual purity and chastity, especially for women, began to influence Indian society, particularly among the educated elite. This colonial influence often reinforced and sometimes even intensified existing patriarchal norms around female sexuality.

Post-colonization, India has grappled with a complex mix of traditional values, colonial legacies, and modernizing influences. While urbanization and education have led to more liberal attitudes in some segments of society, the concept of virginity remains a significant cultural touchstone for many. The post-independence period has seen ongoing debates about women’s rights, bodily autonomy, and the role of tradition in modern Indian society, with the concept of virginity often at the centre of these discussions.

In Christian traditions, particularly within the Bible, the concept of virginity is heavily emphasized through the figure of the Virgin Mary. Unlike the more nuanced portrayals of women in Hindu texts, the Virgin Mary is venerated for her purity and virgin birth, a foundational belief in Christianity. Her perpetual virginity is seen as a symbol of divine grace and purity, elevating her above all other women in Christian theology.

Professor Robert Heimburger, an expert in Bible studies from the Cardiff University, points out, “The veneration of the Virgin Mary created a model for Christian womanhood that equates virginity with sanctity and spiritual superiority. It is important to note that this was not just a theological construct but also a social one. The image of Mary as the pure, ever-virgin mother served to establish a moral code that women were expected to adhere to.” He explains how this perception has deeply influenced Christian communities, where a woman’s virginity often becomes a measure of her moral and spiritual worth.

The idealization of Mary as the “Mother of God” and her virginity as a prerequisite for her divine role has led to a persistent and sometimes oppressive ideal in Christian societies, where women’s value is tied to their sexual purity. Robert adds, “Even today, in some parts of the world, this religious ideal continues to shape societal expectations, often without questioning whether such standards are fair or just.”

The cultural ramifications of this are profound, affecting not only religious interpretations but also societal expectations of women in countries like the UK. Even in modern times, some communities still uphold the idea that a woman’s worth and honor are intrinsically linked to her virginity, reflecting how religious beliefs can permeate social norms.

In the UK, the historical evolution of the concept of virginity has been heavily influenced by its Christian heritage, but has also been shaped by social, political, and cultural changes over the centuries. During the medieval period, virginity was highly prized, with “virgin martyrs” celebrated in religious narratives and the Virgin Mary held up as the ultimate exemplar of female virtue.

…the real question is, is religion telling women these rules, or is it us men who, through religion, are dictating people’s lives, especially women’s?

– Professor Saira

The Tudor and Stuart eras saw a continued emphasis on female chastity, with virginity often linked to notions of family honour and social status. However, the Enlightenment period began to challenge some of these traditional views, with philosophers and social reformers questioning the moral and social implications of such rigid standards.

The Victorian era brought a renewed focus on sexual morality, with virginity once again emphasized as a crucial aspect of feminine virtue. This period saw the development of the “cult of domesticity,” which idealized women as pure, pious, and submissive. However, this era also saw the beginnings of feminist movements that would eventually challenge these restrictive ideals.

The 20th century brought significant changes to attitudes towards virginity in the UK. The sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s challenged many traditional notions about sexuality and virginity. The widespread availability of contraception, changing social norms, and increasing gender equality all contributed to a more relaxed attitude towards premarital sex and virginity.

How could I — wife of the Pandavas, sister of Prsata’s heir Dhrstadyumna, friend of Krsna Vasudeva — enter this hall of kings… I am the wife of Yudhisthira lord of dharma, and equal to him by birth; tell me, am I slave or free?…

-Draupadi to King Dhritarashtra, after the ‘vastra-haran’ incident in the King’s court

However, it would be misleading to suggest that the concept of virginity no longer holds significance in contemporary UK society. While attitudes have generally become more liberal, particularly in urban areas and among younger generations, the influence of religious and cultural traditions means that virginity remains a complex and sometimes contentious issue.

The Quran also emphasizes the concept of chastity, particularly for women, although the interpretations can vary widely across different Islamic societies. Virginity, modesty, and moral conduct are essential components of a woman’s character, as outlined in various verses of the Quran. However, the text does not specifically dwell on virginity in isolation but instead focuses on broader aspects of moral and ethical behaviour for both men and women.

Professor Saira from Cardiff University, who specializes in Islamic studies, provides a critical perspective: “While religion does lay a foundation as to how to live a life, we need to understand that religion is man-made. So the real question is, is religion telling women these rules, or is it us men who, through religion, are dictating people’s lives, especially women’s?” Saira’s point highlights the underlying power dynamics at play—how religious doctrines can be interpreted and manipulated by patriarchal structures to control women’s sexuality and autonomy.

She adds, “It’s essential to differentiate between what is truly spiritual and moral guidance and what has been constructed by human beings to serve their interests. Often, the emphasis on a woman’s virginity overshadows the broader values of equality, justice, and respect for all human beings that religions like Islam advocate.”

It is interesting to note that the concept of virginity has evolved over time, especially in the way it is understood and applied to women. Historically, the word “virgin” did not have a specific association with sexual activity. In its earliest usage, the term “virgin” described a woman who was independent, autonomous, and not owned by any man—essentially, a woman who was “untouched” by societal or patriarchal claims.

Over time, however, the meaning of virginity became increasingly tied to a woman’s sexual history. The focus shifted from a woman’s independence to her sexual purity, reflecting a broader societal shift towards controlling and regulating women’s bodies and their sexuality. This transition from an empowered concept of autonomy to one of sexual restriction reflects the broader patriarchal norms that have shaped gender relations across different cultures and religions.

In contemporary India, the influence of religious texts on the concept of virginity remains significant, though modern attitudes are evolving. Virginity is often still regarded as a virtue, particularly in more conservative or rural areas. However, urbanization, education, and exposure to global ideas have started to challenge these traditional notions, especially among younger generations. The tension between traditional values and modern attitudes is particularly evident in discussions around premarital sex, marriage, and women’s rights.

Similarly, in the UK, while Christianity’s influence remains, the attitudes towards virginity are becoming more liberal and varied. The influence of secularism and modern social values has led to a more diverse range of perspectives on virginity and sexuality. Yet, certain communities still hold onto traditional views, reflecting the lasting impact of religious teachings on cultural norms. The multicultural nature of contemporary British society also means that attitudes towards virginity can vary significantly between different ethnic and religious communities.

As we reflect on the complex tapestry of beliefs and cultural practices surrounding virginity in India and the UK, we are reminded of Saira’s poignant observation about the man-made nature of religious doctrines. Her words serve as a crucial lens through which we can examine and question the ways in which concepts of virginity have been shaped and perpetuated by societal structures, often to the detriment of women’s autonomy and self-determination.

The concept of virginity, as shaped by the Bible, Quran, and Hindu scriptures, reflects deep-rooted cultural and religious ideologies that continue to influence societal expectations around women’s bodies and sexuality. However, as we move towards more equitable societies, it is crucial to question and challenge these narratives that often serve to restrict and control rather than empower.

As Saira aptly puts it, “Religion, at its core, is supposed to guide us towards greater humanity, not serve as a tool for domination.” Understanding the historical, religious, and cultural contexts of virginity is the first step towards a more inclusive and just perspective, where a woman’s worth is not defined by her sexual history but by her character, choices, and humanity.

The discourse on virginity remains complex and often contentious, deeply rooted in religious traditions yet constantly evolving in the face of societal changes. While religious texts and cultural traditions have played a significant role in shaping these concepts, it’s clear that contemporary societies in both India and the UK are grappling with evolving attitudes and values. As we navigate these changes, it’s crucial to foster open dialogues that respect individual choices while challenging harmful stereotypes and expectations.

The journey towards a more nuanced and equitable understanding of virginity and sexual autonomy is ongoing, requiring continuous reflection, education, and societal evolution. By acknowledging the man-made nature of many of these concepts, as Saira suggests, we open the door to reimagining a world where personal autonomy and mutual respect take precedence over outdated notions of purity and shame.