The River Wye suffers from pollution caused by intensive agriculture. In the town of Ross-on-Wye, one dedicated farmer is striving to change this narrative.

Standing at the top of Townsend farm you can see the silver snaking River Wye as it ambles below the fields of Ben Taylor-Davies’ farm.

As he toils on his 520 acres of land, Ben tends to his crops of potatoes, spring barley, and winter rye. Every day in the field he becomes more woven into the chemistry of his soil he uses for his regenerative farming business.

Known locally as ‘Regen Ben’ he can’t understand why more people aren’t blaming him for the problems facing the river Wye.

“I think it’s an oddity, the river Wye, in terms of pollution. What I find very strange is activists go rather hard on the water companies as to who to blame for the pollution in the river,” Ben says. “What people aren’t realizing is based on recent data, seventy percent of the pollution in the Wye is coming from farmers, not water companies.”

Being a husband, father of three, and farmer can be challenging, but living in the Wye valley makes daily life easier. Ben grew up on a farm in Worcester and learned from his father the mental strain of farming, particularly concerning the environmental impact.

Ben’s warm and easy-going attitude made my experience as a visitor to Ross on Wye pleasant. He greeted me in the town center wearing his own ‘Regen Ben’ merch that had a slogan on the back reading ‘Farming that won’t cost the earth.’

As we drove through Ross on Wye’s hilly landscape, I learned quickly just how beautiful Ben’s world is. The valley’s green and yellow pastures resembled a Van Gogh painting. But for him, it was just another day in paradise.

“Farming in the countryside is pretty awesome. It’s something I’m passionate about and something I want to pass down to my children and their children that they will have one day,” Ben says.

Upon our arrival at the farm, I was greeted by his wife, Helen, and one of his daughters, Tegan. They were engaged in some land cleanup, assisted by five horses they owned. At one point, the horses neighed in my direction as if to extend a warm greeting.

Walking on Townsend Farm, you will first see the ‘Great Horizons’ mural, which was named that by his mom Sue who has oversaw 45 years of change on Ben’s farm as it became a more ecological farm for the future.

We walked past some of his side projects that he’s done with his business over the course of a few years. Ben has worked on a vineyard for his wine business that he does and his ‘Chaos Garden’ as he calls it which is a mixture of vegetable, fruit and plant seeds.

At Townsend Farm, Ben’s regenerative farming methods extend beyond crop cultivation. He also incorporates these techniques in raising cattle and chicken. As a result, he offers customers premium-aged wagyu beef and free-range eggs.

We started our drive on his farm aboard his Kubota tractor as his pet dachshund hopped on board for the ride as well. Ben began to explain a bit of his background on his research.

During his time studying geography at Liverpool University and gaining years of experience at agricultural colleges, Ben immersed himself in the study of soils and agronomy.

After visiting other farmers across the world, he realized the harsh reality faced by farmers: the high costs associated with food production and the subsequent deterioration of the environment.

According to the Environment Agency (EA), some of the problems facing the river Wye are due to changing agricultural and industrial practices.

There are other farmers like Ben who were to blame for this increase in pollution in the river. In May 2023, the health status of the river Wye was downgraded by a Natural England report from unfavorable-improving, to unfavorable-declining.

“What we need to understand is farmers need to take responsibility too. All the people I talk to, my neighbors, other Ross farmers, have started to understand that we are the problem too. It’s really strange to see the activism with these groups only really be put against water companies, when really, it’s all of us. It’s the entire contribution,” Ben says.

On Ben’s farm, he practices regenerative agriculture by minimizing mechanical and chemical disturbances to his soil.

Traditionally, farmers implement a method known as ’tillage’ to cultivate crops, which involves digging and overturning the soil. This process often includes the application of synthetic fertilizers and fungicides, which can have detrimental effects on soil life.

As we drove, what stuck out on Ben’s farm was the refreshing aroma of the soil filled the air, creating an invigorating and satisfying experience. The sweet and earthy fragrance was particularly noticeable, leaving a lasting impression.

“We look at using compost extracts while farming and fighting natural fungus on the ground with our fungus. What we’ve learned is that working with Mother Nature makes things a lot easier,” he says. “To be sustainable in terms of farming and all farming practices, you need to be sustainable as a business,” Ben says.

As part of the Farming in Protected Landscapes programme, Ben’s work in regenerative farming has received £65,530.20 in grant money for his plan to enhance the environment and push other farmers to do so as well.

Ben has started a series of nature walks on his farm with other farmers who want to learn on how to have a greener footprint to help save the Wye from degradation.

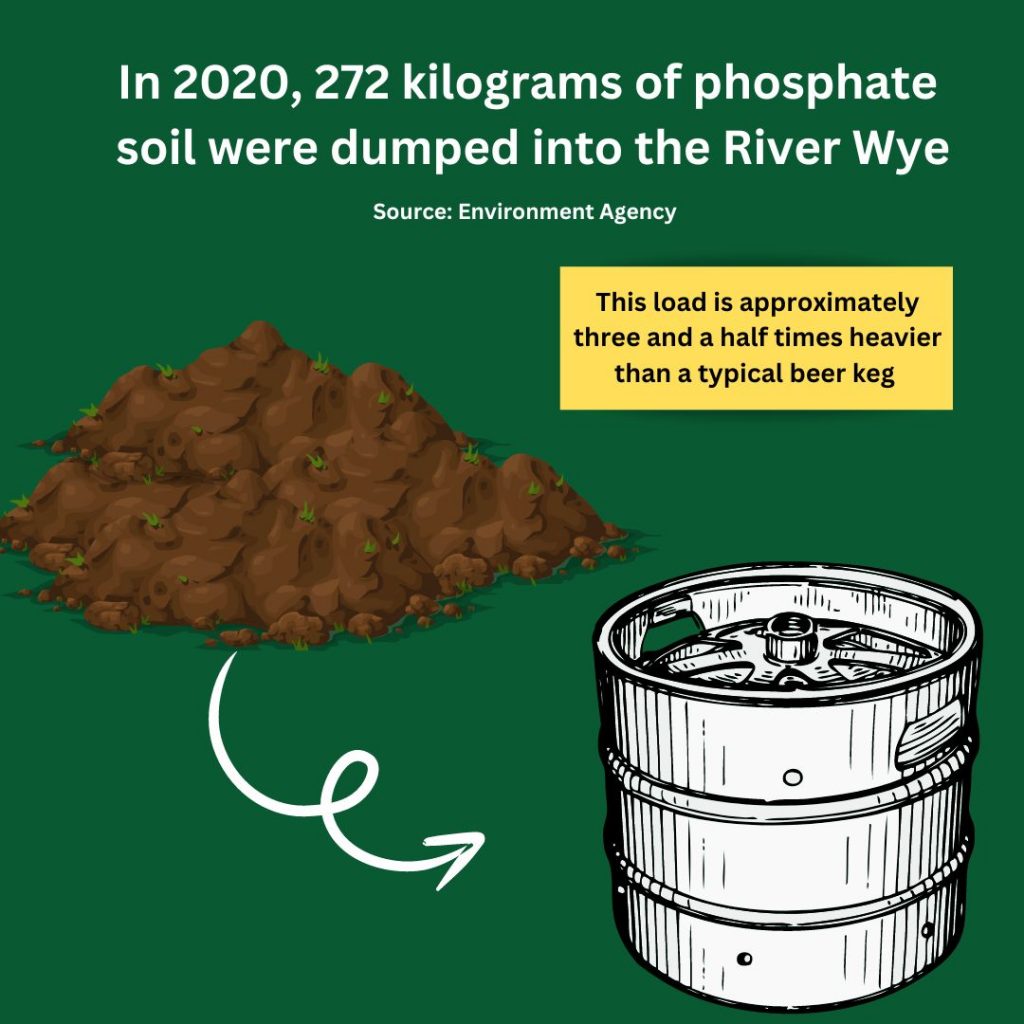

Over the past year, the Environment Agency (EA) has come under fire for its inability to stop the spread of agricultural pollution. Specifically, the EA has been accused of overlooking the protection of the River Wye from phosphorus pollution stemming from agricultural soil.

In aquatic ecosystems, phosphorus from agricultural soil can cause algal blooms in the river Wye, blocking sunlight, depleting oxygen, and harming fish populations. Heavy rainfall causes soil runoff to happen from nearby farms in the Wye catchment, leading to excessive phosphates in the river Wye and eutrophication (dense green algae).

Ben promotes regenerative farming to restore topsoil biodiversity and prevent excessive calcium leaching, addressing river Wye and Environment Agency issues.

“On our farm, we let nature take its course for the river. Rivers are living things, it’s an ebb and flow, it’s a natural process,” says Ben.

We stopped a few times to hop off the tractor and look at some of the crop fields he grows at Townsend. Just by standing at the top of his plot of land for his potato crops, I was greeted by the sweet aroma of an earthy, nutty aroma mixed with regenerative soils.

Through his methods, Ben has discovered that prioritizing his soil first has led him to still be able to produce his crops without destroying nearby land and bodies of water. Creating calcium rich soil is his bread and butter to being a sustainable farmer in hindsight of the water issue.

Ben tries to employ regenerative agricultural practices on a section of the River Wye’s frontage that spans 2.5 kilometers, representing precisely 1% of the river’s total length. His proximity to the Wye heightened his awareness of the severe pollution that had plagued the river in recent years.

“If we’re filling up the river with phosphate and soil, that’s losing profit. If you think about it in general terms, it’s a fertilizer, which you’re deciding to not use but disproportionately putting it in the river, so you’re throwing money away and down into the drain,” Ben says.

Ben often lept in front to guide me around his array of cropping stations. I trailed behind him as he led the way, pushing weeds and bushes of barley to maneuver our way through the field. Herds of sheep were gathered in a commune nearby, quietly watching us go on our adventure.

Over the course of our journey on Townsend, we often stopped to just sit and chat about his perspective on other activists and their goal with the EA. Ben would often shake his head in disapproval when discussing his view of activists and their lack of attention on how farmers are contributing to the problem.

“Water companies don’t always do brilliantly but they are cleaning up their act. That percentage of pollution from them is decreasing. If farmers aren’t doing anything, then our percentage will increase,” says Ben.

Researchers studying rivers have discovered through their samples taken from the lower Wye catchment are exhibiting elevated levels of phosphate. Ruth Leslie, who conducts research in water and environmental engineering at Surrey University, discovered from her data just how dire the situation was.

In rivers, phosphate levels are measured in micromoles or ‘umol’ per liter and typically range from 1 to 13 micromoles. However, in the river Wye, Ruth’s samples revealed an exceptionally high phosphate measurement of 50 micromoles.

“I took some samples from the river for my research near Ross on Wye where there’s a lot of agricultural farms. You’d think by there it would have diluted since it was further down the stream, but the levels were still insanely high,” she says. “I expected it to be more polluted from waste treatment but it was all from agriculture.”

The top agricultural practice that usually takes place in the UK is poultry farming. Chicken farming giants in the UK are mainly controlled by two food companies: Avara Foods and Cargill PLC.

The Wye catchment is home to 500 chicken farms and 1,420 intensive poultry units. Powys, Shropshire, and Herefordshire are known as the ‘poultry capitals of the UK’ due to their high chicken production. All three counties are in the lower-Wye sub catchment.

“Not all farmers are the same, and not all are committed to intensification and production at any cost. Agriculture might be a problem – but regenerative farming like Ben’s is also part of the solution,” says Professor Steve Ormerod, who conducts research in river biodiversity at Cardiff University.

As a response to this catastrophe, Leigh Day UK, a law firm, in collaboration with River Action, has recently initated a class-action lawsuit to address the alarming rate of runoff from chicken farming into the River Wye.

Their claims emphasize a significant increase in poultry numbers in Herefordshire, growing from 13 million to 18 million within a mere four-year period.

Recently, the law firm organised a showcase in various counties within the Wye catchment to engage with residents and activists interested in joining the legal claim and addressing the agricultural issue.

Ben, a concerned individual, decided to skip the showcase due to poor problem-solving among groups, in his eyes. His conversations with anglers and other activists revealed a lack of clarity about their objectives.

“I’d wish some groups would all stop worrying about figures and start discussing short term, medium term and long term solutions because that’s what I never hear,” he says. “It shouldn’t be about who is to blame and where all the blame lies,” Ben says.

As we reached the end of our trail on Townsend Farm, we decided to park the tractor near a patch of bluebell flowers, which were explored by his pet dachshund as lept off immediately to run his fur through the area.

“You can produce an awesome amount of food but you can do it in such a way that increases biodiversity and protects the water. I think the most important thing with activism is that we need to get everyone to take ownership of the problem,” Ben says.

This past summer, a new position of power was set in place in the UK. Keir Starmer, the new UK prime minister and leader of the labor party, has left Ben feeling hopeful for the future of farming in the country.

Surprisingly, while some within the environment space disagree with the former Tory party’s view on the environment, Ben believes their dedication to his regenerative farming movement was phenomenal in his perspective and he hopes the new Labour government will follow in their footsteps.

“As much as I am anti-Brexit and anti-corruption, what they were doing for soil protection and grants for companion planting was an amazing array of opportunities. That government goat farming and the future of the countryside right. That’s what we’re already doing here on my farm” says Ben.

Farmers in Herefordshire are vowing to start taking accountability with their practices after hearing Ben’s proclamations. Between high phosphate levels and visible slops of green slime found in the Wye catchment, they are ready to make a change to their practices.

Ben thinks while this is a great way to hold the higher-ups accountable, there needs to be more push back towards small to medium sized farming businesses and how they produce their soil and stock.

His idea for what the future of farming will look like is one where we begin to understand biological processes of soil which secure the environment, whether that be through activism or through the government.

“We’re quite unique in the Wye valley. There are some short term gains where we can add calcium to the soil by this way and bind it together,” says Ben. “These are the things we should be talking about rather than arguing about who is to blame and where the blame lies.”