A physicist once indifferent to the state of British rivers became the leading co-founder of Friends of the Lower Wye. What has he learned so far in his journey?

When the term “activist” is mentioned, specific images might come to mind. It’s common to associate activism with loud public demonstrations or the sharing of social media graphics.

In the Wye Valley, activism has no specific look or method. Here it is all about putting the needs of the local community first, especially when the conversation is about the River Wye.

Nick Day worked as a physicist in the aerospace industry for years. During the summer, he would always swim in the Wye with his friends and family in Tintern, where he resides.

His village is relatively gray and muddy. However, the Wye was looked at as the ‘beacon of light’ for him. Swimming in the calm, tide of the river, basking in the sun that would overcast all the greenery surrounding him, it became his place for seeking peace.

“That all changed eight years ago when I noticed a slimy, green sludge starting to appear on the top of the river bedsheet,” says Nick.

The scent from this sludge was very putrid and reeked of a sour twang. It would travel throughout his village, and then soon enough, the entire valley started to be covered in a blanket of it.

After retiring in 2020, he became distressed by the state of the river and wanted to prove to doubters that it was in trouble.

“When we stopped going swimming, I’d sort of moan at anybody who would listen to me that the river was in a terrible state,” says Nick. “Lots of people just didn’t really want to listen or know about it. They’d just look at the reflections on the top of water and say “Well, it looks lovely to me” and ignore my sentiments.”

Through research, Nick discovered that the sludge on the river originated from algae blooms. These blooms were a direct result of agricultural and sewage practices along the Wye.

In the month of July 2021, the marches of hundreds of citizens could be heard throughout the valley. Save the Wye, a coalition of citizens who advocate for the river, embarked on a month long pilgrimage along the river from its source to where it flows into the Severn estuary.

The purpose behind this was to celebrate its existence but raise awareness of the degradation it was facing. As they trekked through the valley, the would often break out into song, say poetry symbolizing the river, and greet local communities that they would pass through.

The pilgrimage eventually passed through Nick’s village, where he saw with his own eyes people who were just like him, advocating for the river. He quickly learned that some of those who embarked on the pilgrimage were apart of the organization, Friends of the Upper Wye.

In response to his concerns about the algae blooms forming in the lower-Wye sub catchment, Nick contacted several group members. Although the group shared his enthusiasm for addressing the issue, they were unable to extend their reach beyond a specific point in the Wye Valley, particularly Hereford, due to the logistical challenges of organizing another group.

“I had been in conversation with them before about the lower-Wye subcatchment needing a group. Once I saw them pass through I felt like it was time,” says Nick.

Nick stood in the garden of his local church with an old friend of his, Mike Dunsbee, as he watched those from the pilgrimage walk in a line alongside the river, chanting in solidarity.

Every stride taken by the group sounded off an alarm in Nick’s head that now was his chance to get inspired and start his journey as an activist.

Nick then decided to found his organization, Friends of the Lower Wye, for his community in the lower-Wye catchment. He initiated contact with Cardiff University to assemble a team of volunteer citizen scientists from the lower-Wye region.

“We were stood in the church garden and just instantly went from ‘Why doesn’t somebody do something about this’ to ‘We are absolutely doing something about this’” Nick says.

As Nick managed this initiative, Mike assumed the role of the group’s dedicated campaigner. The two companions became the essential cogs in the machine. Together, the duo became the driving force behind the collective’s foundation.

For the first time in the lower-Wye catchment, a group had come together. Nick understood that by forming this group, it would help give substance to the countless stories and feelings he had gathered from others in his region.

“I never really considered myself as an activist at first, I was only interested in the data, but it began to make me look at things from a wider picture,” Nick says. “Some people will use the word activism in a derogatory way to describe it, whereas for the environment, we’re all just trying to be honest with what we see.”

As of late, Nick has had to take the reigns on both the campaigning and data gathering sides of the group due to Mike undergoing cancer treatment.

His dedication to maintaining the group’s operations while Mike recovers aims to preserve the belief and enthusiasm he has instilled in each member on his team.

“Hes had to take a bit of a backseat and is in a bit of remission in terms of the treatment. We’re doing the best we can in order to save him from thinking he has to do too much,” says Nick.

The initial recognition of their work came from their efforts in collecting data from the river. Nick would often join river scientists in the lower-Wye catchment to take data samples and examine the level of phosphates in the water.

This type of team-building is what united the community within his region. Being a activist to Nick was important, but being part of a community that looked out for each other in times of need like then, is what Nick truly wanted to do.

During the initial stages of data development, Nick’s persuasive efforts led to a successful collaboration with other activist groups located further upstream along the River Wye. These groups generously shared a year’s worth of valuable data collected by their citizen scientists.

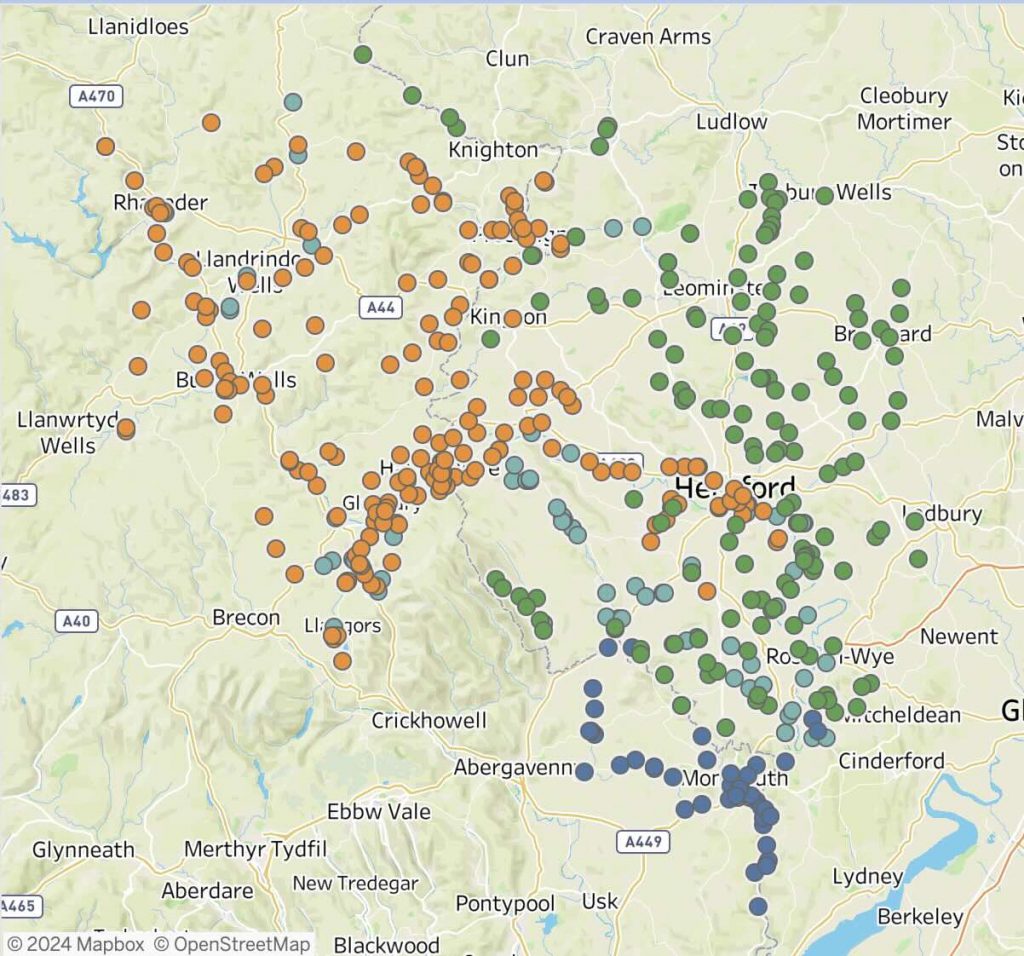

His objective was to devise a map depicting the variation in phosphate levels across the catchment, a work that garnered admiration from his peers.

“I was quite pleased in a way because it backed up what we thought we were going to see. It suggested that things were reasonably consistent in terms of pollution across the river,” says Nick.

During the process of combining all the data, Nick faced numerous obstacles. Gathering such a vast amount of data from his location in the lower-Wye catchment, as well as talking with multiple research teams and scientists from all the other counties within the upper-Wye catchment, proved to be a challenge.

Countless meetings were had in order to figure out a seamless way to combine all the data. Soon enough, Nick teamed up with Michael Carpenter, a data configurator, to create a cutting edge piece of technology that would visually show the pollution surrounding the Wye catchment.

The tool, called “WyeViz”, enables citizen scientists working along the river to visualize and understand data. The map serves as a platform for data collection but as a way to engage the general public who are interested in the river’s well being.

Other groups who also worked along the catchment praised Nick for this incredible idea which helped to funnel all of the data into one system. It led him to reflect on his activism efforts at that point compared to his physics background.

“This has taken up more of my time than I ever spent when I was working as a full time employee,” Nick says. “It’s been an interesting transition. I was initially interested in the data as it occurred but when you get to see what the wider picture tells you about the river, I was more drawn into that.”

As a newly founded group, Nick wanted their members to become associated with other groups within the catchment now that they were able to create a successful database.

Soon enough, Friends of the Lower Wye decided to join forces with Friends of the Upper Wye. Together, they became Friends of the River Wye (FORW). It sent the groundwork for people to start to work with others, despite where they levied in the catchment.

Other groups such as the Wye Usk Foundation and the Wye Salmon Association started to work along side Nick and his people. He was pleased that working with other groups was going well. “We tried to get together as many people as we could, who cared about the river,” says Nick.

Upon seeking funding from pertinent authorities like the Nutrient Management Board, responsible for river management, Nick encountered reluctance from certain parties. They showed hesitation in allocating their profits towards river restoration and preservation efforts.

The times where Nick has ran into issues when it comes to getting the government to listen to him and his group’s sentiments has been far too many to count. He’s grown aware of the weary emotions politicians have towards his journey as an activist for the Wye.

“There’s been stages where people have thrown their hands up in despair because it has gone on for so long with relatively little way of progress,” says Nick. You could get the impression that we were dealing with some large scale interests that were keen to retain their profits and drag their heels when we suggested they needed to change their practices in order to save the river.”

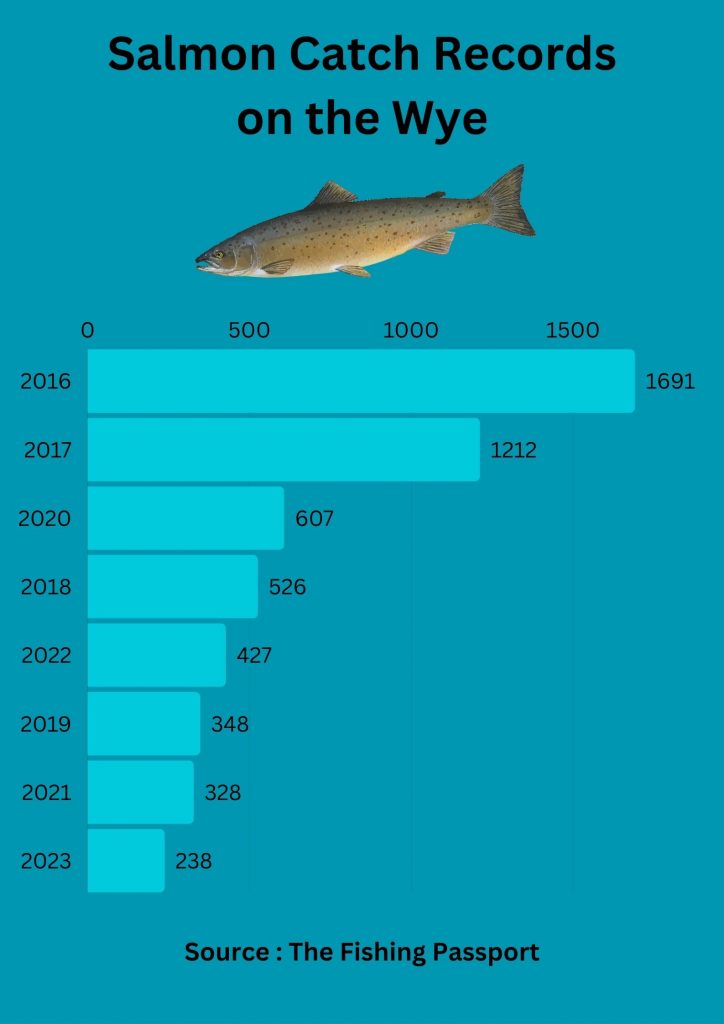

The lingering of phosphates in the Wye can lead to ecological warfare in the water. According to the Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, species like salmon, crayfish, and otters have been affected by agricultural farming in the Wye catchment.

The numbers of the salmon population are very low in the river.In pervious decades, several thousands of fish could be caught. Last year, recent studies have revealed that 250 fish were caught in total in the Wye catchment which has gathered concern between the local communities.

“What really matters is what’s going out there in nature that is out of our control. When phosphates flood the water, blooming toxic algae will form and it will kills the tiny invertebrates that species feed on,” says Dr. Sasha Norris, who is a zoologist and founder of the Herefordshire Wildlife Rescue. “If they have no food, then they will die.”

Flag species such as the native crayfish and the river crowfoot (river weed) would also grow on the Wye besides fish, and they used to be able grew extensively compared to present time.

In the past, the native crayfish and river crowfoot, also known as river weed, flourished extensively in the Wye River. Nick reminisces about the mesmerizing sight of a blanket of white crowfoot flowers swaying along the river’s edges.

However, the impact of agricultural practices and sewage discharge on these species has highlighted the challenges of quantifying environmental science, according to Nick.

“As an ex-physicist I’m used to hard science, which is many ways simpler. You tweak one thing and go one to see what else needs changing. With the environment, you tweak one thing and hundred things can change, each of those things can have knock on effects,” he says.

There is an tendency to oversimplify and attribute blame to a single factor when discussing these populations. However, Nick want the data and the conversations hes having to alert people, to make them them get up and shout.

The cusp of dealing with government and industry practices has made Nick also realize just how hard it is to voice your opinion as an activist.

As a collective, FORW’s activism also includes manifestos. They recently teamed with the Save the Wye Coalition to criticize the Environmental Agency (EA) for failing to protect the river Wye in their manifesto and proposed a water protection zone to stop pollution and a Wye Recovery Fund to support sustainable farming and nature-based solutions.

“The UK government came out with a plan to save the Wye last year and it was garbage, quite frankly,” says Ian Hague, who a member of the Save the Wye coalition. “We had to take matters into our own hands and make a manifesto ourselves.”

In addition to his data-driven wizardry and conversations with figures in gray suits, he actively engages in grassroots activism. Notably, he has participated in marches organized by the Friends of the Lower Wye and has received media attention through his feature on BBC Hereford.

Nick realizes with his work along the Wye that it isn’t just a problem where he lives. It’s a nationwide problem, even a worldwide problem too. He wants people to know that there are issues with rivers in many places.

“I guess you can say that in doing these things, now I would consider myself a bit of an activist,” Nick says. “I started this because you begin to realize that when it comes to the environment, it has very little of a voice. The rights for rivers movement has sparked.”

His bulk of concern for wildlife and ecological state of the river is what keeps him in contact with other groups of citizens who are out on the river everyday. Anglers, wild swimmers, even rowers, are people he has gotten to help support his organization and cause.

Seeing first hand the drop in activity surring the Wye is what he wants people to realize is a crisis. He stopped hearing the cast of fishing rods on the river, the sounds of boat motors going off the grain into the steady waters, the splashes of swimmers, it became a real issue to him.

“It means a lot to other people in various different ways. We encountered interests from these groups about our mission and they’re concerned. There’s a lot to learn from each groups and various effects we can have on the environment. It’s been a very interesting journey,” says Nick.

Nick has noticed there is a spectrum of things that rift between groups. His concern for the future of activism surrounding the river Wye is what he thinks will either make or break the movement.

Extinction Rebellion (XR) is one group that comes to Nick’s mind when he thinks of “extreme” methods of activism.

First founded in 2018, XR is a global environmental movement that claims to use nonviolent civil disobedience to address the climate and ecological emergency. Shockingly, it was placed on a list of ‘extremist ideologies’ by counter-terrorist police for their demonstrations.

Nick believes that for the most part, XR and their methods of activism are for the right reasons. He does believe that there should be situations where a calmer approach can be used in order to get work done.

“When people see methods of activism from groups like Extinction Rebellion, it kind of scares them away in a sense. We don’t know if because they also exist, it’s making people in Parliament and the general public not want to listen to our ideas we have on actually saving the river,” he says.

His end of having a calmer approach with data and focusing facts to present to newspapers and other media channels in order to expose the data, has helped him raise awareness that way.

“You know, I always have the concern if you have too many stunts with your activism, you’ll put a barrier between the people you need to speak to, and yourself, if you’re seeking change with your work,” says Nick.

Other groups Nick has learned about during his activism journey are groups like JustStopOil, who have been in the media for many extreme forms of protest such as blocking roads and disrupting sports matches.

Nick believes these types of activism versus his can coexist at the same time. Nonetheless, with the river Wye he thinks there needs to be a calmer approach due to a lack of consideration and urgency from parliament in the past.

A calmer, approach to activism through showing facts to large government corporations, doing marches, is a way that Nick prefers more.

He believes that from his personal journey as an activist, the people hes met, and his life before and after the pollution in the Wye, that is how to grab people’s attention on this issue.

“Theres lots of things that need to be considered, lots of talks that still need to happen. We are just going to keep striving to move forward,” says Nick.