As the fight for preserving Welsh continues, how has Welsh been politicised and how much is learning it a political act?

When Anglesey Homes, a property development company announced that they were going to change the name of one of their houses in the village of Llanfaelog, Welsh Twitter erupted. The house which is “available for 8 guests” and “pet friendly” was originally called Gwel yr Wyddfa, or View of Snowdon, but the company said it would now instead be called 9 Sandy Retreat.

The response from the self-proclaimed “Welsh twitter” group was adverse. Some called it a lack of respect, others just a plain lack of originality. Some described it as cultural vandalism or even colonisation in action. This marked one of the most recent examples of the lengthy fight surrounding the preservation of Welsh and also how political it can be.

While Anglesey Homes put out a tweet just days later to say that it was the owners – a third party- who had renamed it, there was no turning back. The group had already written nearly 300 negative reviews about the homes to discredit them.

It also did little to change the minds of people who saw the Welsh language entwined with a greater goal – Welsh identity and even independence. Twitter user called John “Sage” Matthews wrote: “How ironic that a company based in Cheshire is doing all it can to dissolve and dilute the local culture in order to attract 2nd home buyers – all while named after one of our islands. #f**kingannibyniaeth”. Or in English, #f**kingindependence.

Luke Johns is a Welsh learner who lives in Cwmbran and works in finance. He also goes by Cymru Luke on his TikTok account where he posts about Welsh independence. “I’ve been quite politically active for a long time,” he says, adding that Brexit and austerity cuts meant that he started looking into the politics of Wales. He says: “Everything’s been decimated, and it always seems to be Wales.”

This is on top of historical inequalities in mining communities like Fochriw – where Luke grew up. Here, Thatcherite policies still have an effect and newer investments like HS2 leave Wales as a whole disadvantaged, according to Luke. “Economists from Cardiff University have said it’ll make Wales 150 million pounds a year worse off because people will bypass us,” he says.

Through his research, Luke has not only garnered facts but has also grown closer to the Welsh language and his Welsh identity – something that wasn’t always there. “Growing up I felt more British than Welsh. You can probably hear my accent. I don’t have a typical Fochriw accent,” he says. “My view was always it was a pointless language to learn. I wanted to learn French, I wanted to learn Spanish. I wanted to learn something that I thought would be useful and I never saw the Welsh language would be of any use whatsoever.”

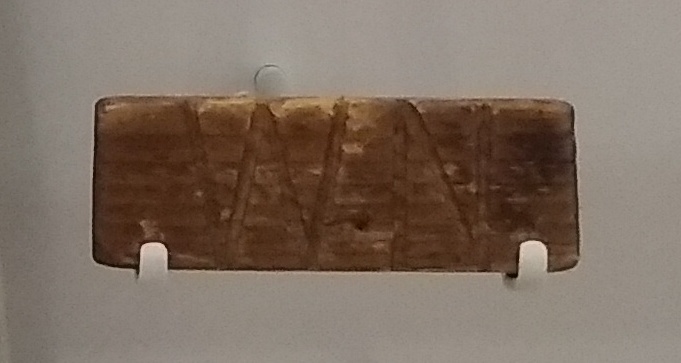

Now, the concept of independence and learning Welsh “overlap” for Luke. The history, the way Welsh was polticised and the inability of many people not being able to speak it all link together. “I read about the Welsh Not. And I found that really, really interesting. You know, the treachery of blue books. The language was basically cut out of our country over the course of two generations,” he says.

All of this led him to question why he didn’t speak Welsh. He now feels like he was “robbed of the opportunity” and says: “I also wasn’t given a choice because it wasn’t a Welsh medium school that I could just easily go to.”

Luke started learning on Duolingo and though Duolingo won’t always be the focus, learning Welsh is. “I’m really committed now to learning Welsh because I just think it’s such an important part of the culture. It was something that was lost, and not by accident in Wales.”

It is, however, a little more complicated than that according to Martin Johnes, professor of History at Swansea University. He says: “The Welsh Not is not a myth. It did exist. It was real. It was horrible. For those who experienced that. But it was nothing to do with government. It was never state policy.” Martin adds that the decline of Welsh was largely due to two things – immigration and families choosing to raise their children in Welsh.

“Some of them did do it because well she was seen as, as a backwards language…as a language of the past,” says Martin. This change in the psyche can possibly be attributed to the Blue Books – where Welsh was described as a moral scourge on the people of Wales.

But, the belief that Welsh was “taken away” is part of a wider cultural trope. Martin adds that it’s “easier” to blame others and more “uncomfortable” to sit with the truth.

Andy Murphy, who lives in Colwinston near Bridgend is a director for YesCymru. He represents South Wales Central for the international non-political campaign for independence in Wales.

Andy says: “It’s important for us to be seen as the voice of people from Wales who believe in Welsh independence, or the people who live in Wales who believe in [independence].” YesCymru is behind the Welsh Government’s bilingual policies but they are not, unlike Cymdeithas yr Iaith – the Welsh Language Society – campaigners solely for the Welsh language.

The language, however, is something to be infinitely thankful for. “If it wasn’t for the Welsh language, Wales would now be a county of England, we would have been subsumed into western England by now,” he says. This can be contrasted with Scotland, which has its own law and education system.

“I think the language has been responsible for Wales being Wales. Without Cymdeithas yr Iaith we wouldn’t have had S4C, we probably wouldn’t have had the Senedd, it kept us going.”

That’s not to say that the Welsh language doesn’t bring problems for campaigns like YesCymru – who want to appeal to as many people as they can. “It also potentially brings problems to us,” says Andy, “for a lot of non Welsh speakers, there’s still this stigma that they can’t speak their own language. And what’s the point? We have to tread that fine balance.”

However, as a whole, for Andy personally and for the campaign, Welsh is part of the future – and would be a big part of an independent Wales. “I think we sometimes do the language a disservice when we talk and talk about it. In that sense, we talk about it from a historical and a cultural and an emotional sense, which it is, but it’s so much more than that. It really, really is. It’s a living language,” he says.

Kierion Lloyd, a Welsh learner from Wrexham, is also of the belief that Welsh is a living language. While many online commentators like to suggest that Welsh is a “dead language”, that can’t be true as Kierion says: “ If I’m learning it, it can’t be dead.

“And I’d like for other people to also contribute if they want to,” he says. “I’d like it to be the option where if you come to Wales, like you would, if you go to Spain, most people are going to speak English, but most of the time they’re speaking Spanish. Why shouldn’t we have that same environment here? We are not England. We are not Scotland. We’re not Ireland. We are Wales. Some of us speak Welsh. And for tourists coming in that might be a novelty for them.”

Yet, arguments are still made that Wales is not a country, but a principality of England. This is not the case for Kierion, and the distance was only confirmed during the pandemic. “I’ve always voted. But I’ve never really been aware of politics and then when the pandemic hit,” he says. “The first thing it really opened my eyes was when Boris Johnson’s Westminster Government prevented Wales from importing its own PPE. It was brought into the UK, and Westminster distributed it as they saw fit. So that made me think: well, hang on – we are our own nation.”

Add to that Plaid Cymru MP Liz Saville Roberts being “shut down” for speaking Welsh in the House of Commons when MPs such as Jacob Rees-Mogg have previously spoken Latin, something was something that riled him. “Trying to tell a politician they can’t speak Welsh in the chamber? Well, okay. You tell those Eton boys, they can’t speak Latin. You’ve got to have some sense of consistency.”

All of this acts as an incentive to speak Welsh as a form of rebellion. “I just feel that it probably is a bit of a fight back by learning Welsh. It’s it’s almost the two fingers up to Westminster and to the English parliament,” says Kierion. Though he’s not “anti English” he is “very much anti Westminster control,” and sees this extend into other issues like second homes – particularly in the west and north of the country. “Wales is often seen as another colony,” he says, “it’s now like the colony has come in and taking over that beautiful parts of the country.”

People moving into predominately Welsh-speaking areas threaten the continuation of the language. “We’ve seen a lot more stories now around second homes issue in Wales,” he says, “so many second home owners come in that the residents have moved to haven’t been able to afford to buy and have to move away. And therefore the Welsh language schools had to close down.”

Keeping the language alive is important to Cymdeithas yr Iaith which has argued that second homes are “destroying” Welsh-speaking areas. But there is a bigger picture, according to Martin Johnes, professor of History at Swansea University. “Holiday homes is an easy kind of place for blame,” says Martin, “and an easy policy target.

“You need affordable housing. And you need jobs. You need to keep young Welsh people who grew up in this community, who speak Welsh – you need to stop them moving to Cardiff or Swansea or London or Birmingham.”

Andy and YesCymru see Welsh as a unique selling point and a way to bring economic benefits. “It’s actually really, really fundamentally important to our future as an economic nation,” he says. “Firstly, if you have a truly bilingual country, then they quickly become trilingual,” he says, “we do know that if you look at international trade, the ability to speak different languages.” There is also the possibility to “promote it correctly”, so that it can be a key part of the Welsh tourism offer, something Andy adds: “Then [be] able to play on that culture and the history.”

Ultimately for Andy, it’s a matter of ownership, sovereignty. “It’s our language,” he says, “it’s important because it should belong to everybody, whether they can speak Welsh or not.”