In Rootbound, Alice Vincent’s balcony garden helps to fix her broken heart. In Bird Therapy, Joe Harkness’s birdwatching gives him solace from his mental illness. Why is this new wave of nature memoirs inspiring people to get outside for their mental health?

In the 12 months following Alice Vincent’s break-up, plenty changed. The journalist went on a solo trip to Japan, changed her home address more than once and met a new romantic partner. But, one thing stayed a constant.

“I found an awful lot of courage from the sense that nature keeps going regardless,” says Vincent, the author of Rootbound. Her nature memoir recalls the changing seasons of those 365 days in the wake of her heartbreak. Gardening on her South London balcony, watching buds bloom and leaves decay in local parks and visiting botanical gardens abroad, all started healing her broken heart.

Though nature may have had a profound effect on her, she didn’t ever think Rootbound would help anyone else. “It felt like a profoundly normal thing to go through. Everyone gets their heart broken,” she says. It may not have been written with the intention of helping other people, but the response Vincent has received for Rootbound suggests it has done exactly that.

“I get messages from people saying it has helped them with all sorts of things. Among them: grief, depression, heartbreak. That is always incredibly humbling, and genuinely surprising and touching every time.

“There was one from someone who used to garden a lot and then stopped for various reasons […] something very traumatic happened to them, and having read the book they felt compelled to start gardening again.”

Despite the increase in doctors prescribing nature for mental health and the growing evidence detailing its benefits, storytelling in nature literature like Rootbound has a huge part to play in getting people outside for their mental health.

“Scientific evidence fails to inspire me. I needed to be inspired to make the move out of my front door to find nature.”

Hannah Harrison, reader

Hannah Harrison, a 46-year-old craft tutor from Oadby, Leicestershire, says that walking in nature has been hugely affecting. “It has made a big impact,” she says. “If I miss being outside and engaging in nature in some way, even for a day, I feel lethargic.”

From Seeking Slow by Melanie Barnes to The Wild Remedy: How Nature Mends Us by Emma Mitchell, Harrison credits books for inspiring her to turn towards nature.

She chose books about the benefits of nature at a stage of her life when the monotonous, demanding routines of being a mother, working and running a household were making her stressed.

“I was feeling lost, was busy meeting the needs of others and neglecting my own.

“The books on nature gave me a feeling of freedom – fresh air, the changes in seasons and plants, and the way in which nature works. […] Focussing on small details in a book helped me to find them out in nature.”

Scientific facts about nature’s impact on the brain didn’t have the same effect. “Not for me,” she says. “Scientific evidence fails to inspire me. I needed to be inspired to make the move out of my front door to find nature.”

Jessica J. Lee, who wrote her 2018 memoir Turning about finding solace swimming the lakes of Berlin, says these nature memoirs are essential in communicating the benefits of nature. “It helps hit home with people’s experiences; rather than presenting cold facts or a list of ‘how-to’s for mental health and well-being, I think reading a writer’s journey allows a reader to inhabit their mind for a while, to process and compare to their own experiences.”

We communicate, understand and navigate the world using stories. In fact, according to neuroeconomist Professor Paul Zak, stories can change the very neurochemistry of our brains – character-driven narratives often cause the production of oxytocin, tension stimulates cortisol and a happy ending gives us a hit of dopamine. It’s what sucks audiences into the action of a James Bond movie or lets an advert on television move them to tears.

Storytelling is important in capturing readers’ attention and moving people to action. “The key about storytelling is that it engages readers,” says Stephen Moss, a naturalist and the author of over 30 nature books. “It always has done since the first caveman/woman sat down and said: ‘Once upon a time.’”

He says that the most commercially successful nature memoirs have the most honest, personal stories. “Nature writing has become this huge phenomenon in the last decade,” he says. “The big sellers are all about the human aspect. They’re all very open about their emotions and the situations they’re in. They seem to strike a chord with people.”

Dr James Canton, a nature writer and the course director of MA Nature Writing at the University of Essex, credits one book for the re-emergence and altering of the nature writing genre. “I think the biggest single shift was the success of H is for Hawk,” he says. “Nature writing is being re-established as a core form of writing and reading in non-fiction form.”

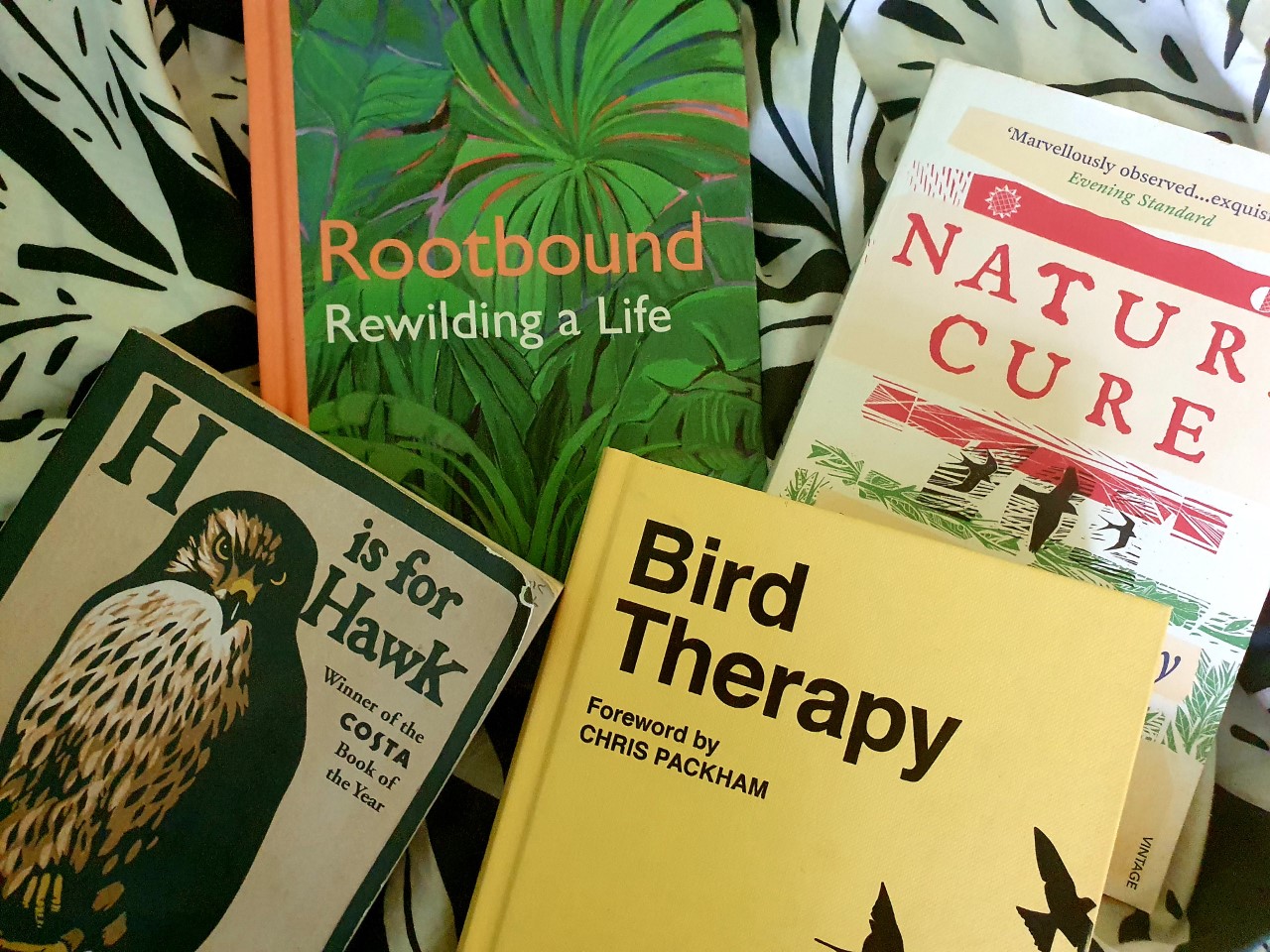

Helen Macdonald’s 2014 memoir H is for Hawk follows her attempt to train a notoriously ferocious goshawk in response to her father’s death. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies worldwide. Some of the books in the ensuing trend include 2015’s The Outrun, Amy Liptrot’s Sunday Times Bestseller about returning to her childhood home Orkney during a struggle with alcohol. She finds early morning swims and tracking wildlife helps her to recover from addiction. Published in 2019 and crowdfunded by 873 donations, Joe Harkness’s Bird Therapy describes the respite birdwatching gives him from his obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety. And in 2020, Alice Vincent’s Rootbound was published. These are just a few of the numerous nature memoirs that have been released in the last decade.

The appeal of many of these introspective nature memoirs is the simplicity of their storyline, which readers at all levels can grasp, says Dr. Canton. “When you just get a simple story with a simple narrative of something like ‘I went and stood next to an oak tree and I felt better’ – we can all get that.”

Studies have shown that nature can be good for mental health. For example, a study led by neuroscientist Dr Andrea Michelli at Kings College London found that a single exposure to nature can produce positive effects, like feeling happier, for up to seven hours. Research by The Wildlife Trusts found that those experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress felt ‘significantly better’ after being a part of conservation efforts.

“It’s definitely really good. But it’s like taking a pain killer is really good if you have broken your leg – it’s not going to fix the broken bone.”

Alice Vincent, author of Rootbound

But Richard Smyth, a novelist, critic and wildlife writer, is sceptical of the ‘nature cure’ narrative in some of these memoirs. “You’re heading for disappointment if you think that going out and turning over a spade is suddenly going to cure your chronic depression,” he says.

“As with all simple things, it’s appealing because it’s simple,” he says. “It’s why quack remedies down the centuries have been so readily adopted – it’s because they promise easy answers.

“Who wants to have to work hard? Who wants to have to think too much? If you’re feeling crap, for whatever reason, who doesn’t want to reach out for an easy cure?”

Boiling nature’s benefits down to a simple narrative is something that Vincent is also careful of. She considers herself ‘blessed’ with good mental health, with no diagnosis for a mental health condition. So, when people come to her to talk about how gardening helps your mental health, she does not want it to be a one-dimensional discussion.

“It’s definitely really good. But it’s like taking a pain killer is really good if you have broken your leg – it’s not going to fix the broken bone.”

And throughout Bird Therapy, no matter how much birdwatching helps him, Joe Harkness never claims to be cured by it. In the closing pages of the book, he writes about the other lifestyle changes he’s made and support he has received since starting birdwatching.

Smyth says this is an example of a good, balanced account of how nature can contribute to better emotional wellbeing.

“I wouldn’t like to dismiss a whole genre or subgenre of nature writing. Joe’s book is a great example of something that does make sense. He writes very specifically about medication and also nature for him being a method, a process – not just something where he steps outside and feels better.”

Further, Moss says that while H is for Hawk is a memoir about dealing with grief, the reader comes to realise at the end of the book that after training Mabel the goshawk, Helen MacDonald had not yet come to terms with her father’s passing.

Even if the current wave of nature memoirs has captured people’s attention, and has the capacity to get those who read them outside for their mental health, Vincent believes it’s time for a change in who’s writing the stories. “I do think certain narratives are getting exhausted – including Rootbound. I think that there’s space for new angles on it.”

One of these new angles is a more diverse range of writers. An endeavour to improve representation in nature writing is The Willowherb Review, a digital platform led by Jessica J. Lee, which champions the work of both emerging and established nature writers of colour. And Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty, a 16-year-old with autism, has been met with praise from the likes of Chris Packham and Robert Macfarlane.

The future of nature memoirs is one that Lee hopes sees these more diverse voices take centre stage.

“I think we’re seeing a big sea-change in what a nature memoir might be; in particular, we’re hearing from more women, people of colour, disabled, and working-class writers. And that is broadening the appeal of the genre and allowing writers to really break new ground.”

“The key thing is that they can’t just be a temporary trend. We need a sustained change in the range of stories we’re telling, platforming, and reading.”