Over 200,000 Indian students step into the streets of the UK each year, entering a new chapter in their academic journeys. How does being in the UK make them think differently about the history and relationship between the two countries?

Sneha Mukherjee came to her dream college and country to pursue her undergraduate degree, but being in the UK made her question the unnecessary obsession her family had with studying in this country.

Coming from a scholarly and musical Bengali family in Calcutta, India who had been obsessed with British education for generations, she became a star in the family for getting into King’s College, London.

“My great-grandfather was one of the rare elite Indians to come to Britain to study law during colonisation. For this, my family considered getting a degree from a top UK university to be one of the finest achievements,” said Sneha. “What they don’t understand is that my great-grandfather and other Indians during the 1900s did not have a choice.”

During the British Raj, the Indian elite such as zamindars, aspiring lawyers or doctors considered British education a form of prestige during the 1840s. This was a prevalent phenomenon among scholarly Bengalis or Christian converts in the country at the time. For some professions such as being a barrister or in the Indian Civil Service, it was compulsory to get British qualifications from 1853 to 1923.

“Though I dreamt of going to attend King’s College for my ambitions and goals, I cannot deny that I was influenced by the mindless admiration of going to London ‘to keep up the name of the family’,” she said. “I never realised how overhyped the British university culture was among privileged Indians right now.”

While studying some of her core modules, Sneha noticed that most of the literature was very British, Irish or European, with very little inclusion of literature by Asian or Black authors. “The syllabus was not diverse enough for students coming from places other than Europe. As an admirer of several Indian poets and authors, I would not have minded pursuing my bachelor’s in India for a different experience.”

On the other hand, Sneha also had some proud moments as an Indian in the English capital. She spotted the statue of UCL (University College London)’s most popular South Asian alumnus at 23, Gordon Square.

“I felt elated to see Rabindranath Tagore’s bust which I had no idea about before coming to the UK. As a Bengali, it was a very proud moment for me for I had grown up with ‘Rabindra Sangeet’ and Tagore’s poems as an integral part of my culture,” Sneha said. The bust was inaugurated at the poet’s 150th birth anniversary at Gordon Square. Tagore was the first Asian Nobel Prize Winner, who had written the national anthems of two nations- India and Bangladesh.

Not far from the bust, lie two spectacular statues of Mahatma Gandhi at London’s Tavistock Square and Parliament Square, both signifying his fight against the British Raj through ‘ahimsa’ or non-violent protest. Like Tagore, Gandhi was also a notable alumnus of University College London.

As a Bengali, it was a very proud moment for me for I had grown up with ‘Rabindra Sangeet’ and Tagore’s poems as an integral part of my culture

Sneha Mukherjee

Nick Booker, a native of England’s Somerset, is an enthusiast of Indian culture and heritage. He talks about the presence of various aspects of British Colonial rule in India and has posted over a hundred videos on his Instagram page sharing insights on the relationship between India and the UK.

“The original English East India House is located on London’s Regent Street, right opposite ‘Hamley’s’, the biggest Toy brand in the world,” said Booker. He indicated the irony behind this where India’s biggest billionaire, Mr.Mukesh Ambani is now the owner of the original British Toy brand.

He showed how one can find a lot of India and its history on various English streets, especially in London. “The English East India operated from Britain after moving to Philpot Lane. They were only able to establish their presence on mainland Peninsular India after landing near Surat on their third voyage.”

With the hype around London’s popular landmarks among newcomers such as the London Eye, Buckingham Palace and Tower Bridge, it was the monuments connected to India that caught Sneha’s eye.

“Peer pressure led me to see Big Ben like any other tourist but what caught my eye was the Mahatma Gandhi statue on Parliament Square which was just a few minutes away,” she said. “Seeing a piece of my country made me immensely proud, making me realise where I truly belonged.”

During her time in the UK, Sneha participated in activities where she could represent her country and share more stories about its history, culture and people. She became the president of her university’s India Society and made sure to provide Indians with an immersive experience of Indian history in the UK.

“While in London, I felt more connected to my culture than ever before and had a pull to connect with the history and culture of different Indian cities,” she said. “Realising my true interests and the struggles I have faced as an International student, I want to explore new options in Delhi or Kolkata.”

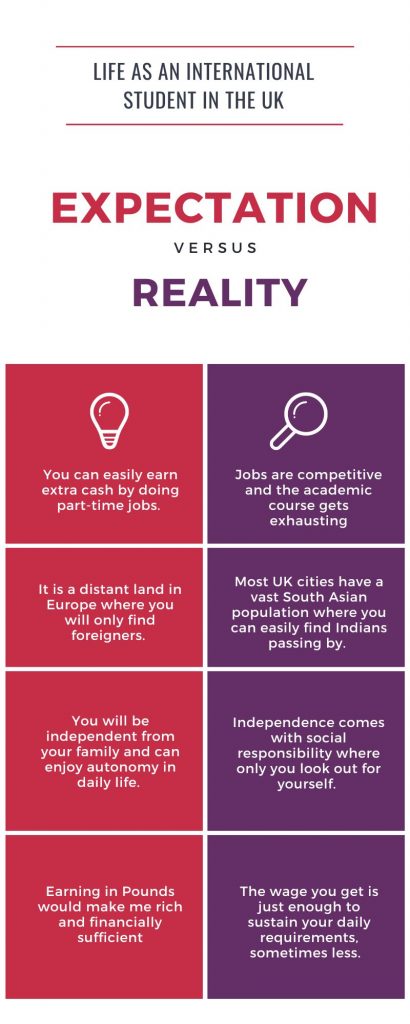

Being in London for over two years, Sneha realised how unnecessarily expensive living was and how facilities were not as ‘modern’ as Indians would expect them to be. She noticed the railway system being nearly as inconvenient as in India, with medical services facing a severe backlog and London being a highly unsafe city for people to live in.

“The entire idea of the UK and especially London is very romanticised among Indians for which they are dying to come here to study and enjoy their life. But the high prices and underdevelopment of many areas would make India a better place to live in,” she said.

In the last year itself, the UK saw over 400,000 international students coming from South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Out of these, about 135,000 alone were from India coming to the UK to pursue higher educational degrees.

The entire idea of the UK and especially London is very romanticised among Indians for which they are dying to come here to study and enjoy their life.

Sneha Mukherjee, student

Pallavi Bose is an employee of an overseas education guide group based in India which counsels and guides aspiring students to apply to universities in the UK to pursue undergraduate and postgraduate courses. She talks about how the pattern of Indian students coming to the UK has changed over the past few years.

“Earlier it seemed like only students with scholarships or ones from affluent families aimed to pursue higher education in the UK as they could afford it,” she said. “However, now it has seemingly become competitive or a sign of prestige in society to send one’s children to the UK even if they are compelled to take an education loan with very high interest rates.”

Bose pointed out how pursuing a master’s degree in the UK has become so common in India that families would rather mortgage their house for an education loan than be the only ones in a social group ‘to not send their children abroad’.

Like many, it had been Shruti Deb’s dream to study in the UK since she completed high school, but the high costs associated with undergraduate study pushed her to pursue a master’s in 2023 after taking an education loan with her family’s help.

“One of the biggest reasons my family and I had romanticised studying in the UK is the influence of Bollywood,” she said. “It all started from Shah Rukh Khan’s ‘Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham’ that created a divine picture of London making Indians crave it.”

Like Sneha, the expense and shortcomings of the UK also took Shruti by surprise, almost making her doubt the decision to come to pursue her master’s abroad. She realised that neither Bollywood nor the stories of her extended family in the UK could prepare her for this journey.

“My romanticisation of the UK took a turn the moment I visited the British Museum in London. With so many artefacts from India, I felt I was home and not in the best way,” she said.

It was through her school history lessons and stories from her grandfather that Shruti learned about the Indian freedom struggle and how the British exploited Indians during colonisation. She had never felt the seriousness of it outside history books until she visited popular UK museums and saw thousands of Indian artefacts herself.

“When I visited the famous locations where Bollywood movies were shot, I thought I was in the place I always wanted to be. Big Ben and Trafalgar Square were just how I had imagined them to be, but the museums changed how I looked at the UK,” she said. Shruti understood why there were so many jokes made about the British Museum where many called it chor bazaar (thief market).

From the ‘Koh-i-noor’ diamond on the Queen Mary Crown to Amravati marbles at the British Museum, the number of Indian artefacts currently in the UK is unknown owing to the complicated country history of its acquisition- whether it was by means of smuggling, stealing or gifting? Since 1970, the Indian Government has attempted the restitution of several artefacts from the UK.

“It is sad that Britain refuses to return its artefacts and continues to cling to its colonial past,” Shruti said. “But I think it is sadder that we Indians pay over 30 lakh Rupees (£30,000) for the desperate desire to come to the country against whom our ancestors fought to gain independence 78 years ago.”

Like many other Indian students, the 22-year-old looked at going abroad as ‘a way out’ from social pressure and getting the freedom to explore the world without restrictions. With the present culture of South Asians going to the UK, the USA or Australia to pursue higher degrees, many resort to taking out loans or spending their family wealth.

“I regret taking an education loan without assessing whether it was truly worth it and if there would be opportunities to easily repay it. However, the current job market looks extremely saturated with competition rising rapidly,” she said.

Following her time here, Shruti could confidently conclude that she drastically overestimated the UK as a ‘first world nation’. According to her, Indians consider places like the UK and the USA extremely developed with advanced services. “The reality was nothing like everyone imagines, almost every service is slow and there is nothing we don’t get back home.”

But I think it is sadder that we Indians pay over 30 lakh Rupees (£30,000) for the desperate desire to come to the country against whom our ancestors fought to gain independence 78 years ago.

Shruti Deb, student

After spending a year in the UK, she would have preferred to go back home after completing her degree and leave the high costs of living, gloomy weather and unappetising food that Britain offers. “Unfortunately, I am not privileged enough to go back home right after my degree, I will not get a job good enough to pay back my student loan. At least here I can look for odd jobs which could pay me for basic sustenance.”