Charities are filling the gaps left by drama schools, but with costs rising and mental health needs growing, is the industry setting its next generation up to fail?

The rehearsal room is buzzing, its walls echoing with the sound of breathing exercises and excitable chatter. At Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, a small group of postgraduate acting students warm up for a long day of rehearsals, stretching their muscles and voices, filling the space with a chorus of vocal sounds. For many, this is the culmination of years of auditions, rejection letters, and sacrifices made in the hope of stepping onto a stage as a professional. But beyond the warm-ups, line readings, and vocal exercises, there is something greater waiting in the wings: the question of how these young actors will cope with the psychological weight of training and the instability of the industry waiting for them outside the safety of drama school.

For Jack Richards, 27, that support is not just an added extra, but a built-in safety net. “Bristol has been really good,” he says. “They employ a school counsellor whom you can visit free of charge. Through Problems Shared, they provide up to six free sessions with a licensed therapist. It’s the most support I’ve gotten from anywhere.” His voice tightens as he compares it to his time at his previous training institution, Birmingham Theatre School. “There, the school offered nothing in terms of support. I remember sitting in a class, and a full-blown argument broke out, and there should have been support offered in those situations. Here at Bristol, it’s insane how different it is. People actually make use of the support. You feel really held here.”

Richards’s experience reflects a reality for many performers. In the scope of UK drama schools, support for mental health and wellbeing is inconsistent, sometimes sound, sometimes absent altogether. Some institutions have embraced in-house counsellors, therapy partnerships, and wellbeing workshops. Others, often blaming financial strain, have left students to fend for themselves. At Bristol, Richards sees the difference that investment makes. “Because the training is so intense here, they recognise students need that support. It shocked me that there is this kind of support out there, coming from a theatre school that didn’t have it. It should be the standard. It’s the bare minimum, really.”

But even Bristol Old Vic is not immune to the financial turmoil the creative industries are currently facing. Richards explains how the school has struggled to keep its flagship BA acting course running. “The cost of three years of training doesn’t cover what it actually costs to train a student. They’ve been in debt to every BA student. To survive, they felt the only option was to cut the BA course, at least temporarily. My course, the MFA in Professional Acting, will be the only theatre acting course moving forward. It’s uncertain. Teachers are leaving because they want stability. The school has been great; they’ve communicated everything clearly, but from the university our school is affiliated with, it’s been radio silence. I think the BA students are feeling very forgotten”

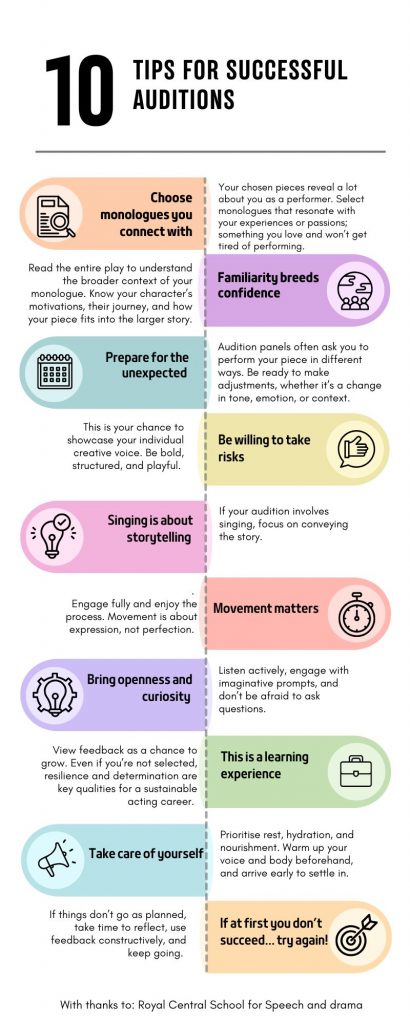

The precariousness of this profession begins long before students even enter the doors of a drama school. Richards auditioned for four years before finally securing a place. “Each audition is fifty pounds,” he recalls. “In one year, I spent around four hundred just on fees, and probably a thousand overall when you include transport and headshots. That’s what turns people off. You’re spending so much money just to get told no, and most of the time, you don’t even get feedback. Birmingham Conservatoire was the only school that did. Everywhere else, you’re left wondering what you did wrong.”

Richard’s journey to success has been far from smooth sailing. He began his training at Birmingham Theatre School back in 2015. This lasted for two years before he started the gruelling audition process for drama school. After four years of rejection, he completed an undergraduate degree in Drama and Theatre Arts at the University of Birmingham. After many years of hard work, rejection and specialist training, Richards has finally been accepted into a leading theatre school.

It was only through external training, with acting coach Tracy Skreet, that Richards found the support he needed. “Without her, I wouldn’t be where I am now. She helped with monologues, self-tapes, and audition speeches. But again, you’ve got to pay for that. Nothing came for free.”

Drama schools remain the most secure route into the industry. Richards referred to it as “your best shot,” offering showcases with agents and guaranteed industry exposure. “You can act without going to drama school,” he says, “but it’s your easiest option. It’s the hardest audition you’ll ever do, but once you’ve got in, you’ve got the training, the contacts, the skills. Even if you leave without an agent, you’ve got something.” What he finds most valuable is the connection to current industry voices. “We’ve had Katie Carmichael, an actor who works closely with Bristol, come in and give us the most honest insight into what the industry looks like right now. She’s gone through Spotlight profiles with us one-to-one, shown us how to write emails to agents, and prepared us for audition rooms. Without her, I’d be lost. This should be standard everywhere.”

Richards’ experience highlights a divide across the theatrical education structure. While some schools provide updated, practical guidance, others often promise false realities. “The staff at drama schools are knowledgeable,” he says, “but their experience isn’t always current. It’s like reading a first edition when there’s already a second edition. If they don’t have the knowledge themselves, bring in the people who do.”

The challenge of bridging those gaps is one that charities like the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine (BAPAM) and the Actors’ Benevolent Fund (ABF) are addressing. When schools can’t maintain adequate levels of support, they step in.

Phoebe Butler, 35, works as a Training Manager at BAPAM. She spends her days handling calls from performers whose mental health has crumbled under the pressure of their profession. A former musician herself, Butler knows how easy it is to burn out. “We’re a specialist medical charity, funded by industry partners like Help Musicians, Equity, and the Royal Variety Charity. If an actor calls to say they have a health issue preventing them from working, we book them in for an assessment with a specialist. At the end, they’ll get a letter to take to their GP or hospital, or sometimes just advice on exercises or techniques. We’re not a replacement for the NHS. We work alongside it, but we understand that telling someone to just ‘stop performing’ isn’t realistic.”

That industry-specific understanding is critical. “All our clinicians are experts in working with performing artists,” Butler says. “One’s a psychotherapist and drummer in Babyshambles, others are physios in the West End. They know the pressures. Research shows that 75% of performers will sustain an illness or injury that stops them from working at some point. We see it every day.”

BAPAM’s support goes beyond clinics. Butler has overseen a growing programme of online workshops, many in partnership with ABF, covering a range of topics including self-esteem, rejection, ADHD, and neurodiversity. “They’re not therapy,” she clarifies, “but they’re psychoeducation sessions, run by clinicians who are also performers. It’s information, tools, and strategies. Today’s session sold eighty tickets, with forty-five people showing up. That’s huge for us. Demand is going up every year.”

Actors, stage managers and musicians log into Zoom from bedrooms, rehearsal rooms and kitchen tables across the country. For many, it is the first time all week they’ve been in a space where they don’t need to compete, perform or impress. In this case, BAPAM teams up with ABF, beginning the webinar quietly. Clinicians, often those who also work in the industry themselves, introduce the theme of the day, which might be self-esteem, coping with rejection, or how to set boundaries in an environment where “yes” is the default response.

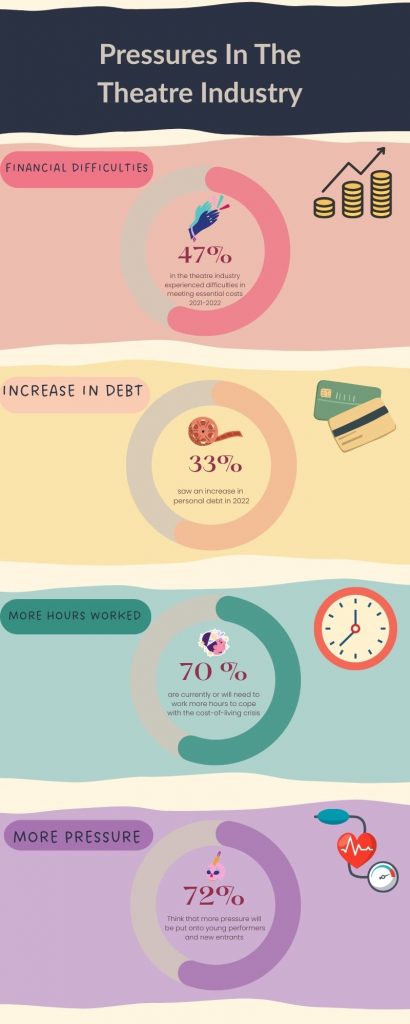

However, funding is again a barrier. Butler describes the struggles organisations are facing post-pandemic: “During COVID, charities gave so much. Now they’re panicking because costs are up for everyone. We’ve had to pull back. And yet, the issues persist. Worse, even. Vocal health problems are rising. Burnout is rising. We see it constantly.”

Tasmin Keeley, who manages applications at ABF, has witnessed the shift first-hand. “When I started nearly seven years ago, most of our applicants were older actors who had retired or could no longer work. Now we’re seeing younger and younger applicants. Mental health is a huge factor. That’s why we introduced six funded sessions of counselling, and why we run webinars with BAPAM. We saw people struggling to access NHS services, waiting months for therapy, and that just wasn’t sustainable.”

Keeley emphasises that the ABF’s support is both financial and pastoral. “We help with living costs if people are signed off, but we also cover physio or vocal therapy costs, because if someone can’t use their voice, they can’t work. We also try to focus on prevention. We’re piloting social isolation events, such as coffee afternoons in Manchester or elsewhere outside London, so actors can come together and share their experiences. It seems small, but when you’re used to the isolation of freelance life, it makes a difference.”

Like Butler, she acknowledges the stigma that still lingers. “People don’t want to be seen as weak. Acting jobs are rare, and no one wants to risk losing one. However, what we hear most often in feedback is not just that we provided financial assistance, but that we listened and that people felt understood. That’s huge.”

At an institutional level, schools are slowly adapting. At LAMDA, one of the UK’s most prestigious conservatoires, Chief Executive Mark O’Thomas has made wellbeing a priority. “We employ a wellbeing manager who’s essentially an in-house counsellor. Before, we paid for external services, but that wasn’t always accessible. Now, students can walk in, book regular appointments, and, if necessary, we still make external referrals. We also employ a full-time disability coordinator who works with students on learning agreements and ensures adjustments are made without stigma. You think, how did we ever cope without these roles?”

The demand for mental healthcare reflects the urgency of the issue. “We’re tiny compared to a university,” O’Thomas said. “We have about four hundred students, but we employ two full-time people just focused on wellbeing. If you multiplied that across the whole university sector, you’d have enormous teams. We’re fortunate because we’re small and get to know our students by name. That intimacy helps. But the issues have grown exponentially since COVID. There’s more openness now, less stigma. And that’s good. But it means demand has skyrocketed.”

O’Thomas is honest about the challenges that schools face. “Drama school is a safe space, but it has to prepare you for an unforgiving industry. One graduate told me they felt spoiled here because on film sets, everything is rushed, and no one cares if you need more time. So we walk a fine line: we can’t just throw students in the deep end, but we also can’t shelter them so much they’re unprepared for reality.”

The conversation about casting is particularly rife. “Students complain about casting decisions,” O’Thomas admits. “We spend huge amounts of time ensuring roles are distributed fairly, considering identity, race, gender, and making sure opportunities are spread. However, in the industry, casting can be brutal. It’s shallow. It’s about how you look and sound. Stereotyping is still an issue. We can’t shield students from that; we can only prepare them. Sometimes that means making choices that aren’t popular, but our goal is to make sure graduates can play a range of roles and get representation.”

Representation is the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, the bridge from training to industry. O’Thomas, “Some students are signed before they graduate, others get no interest. It’s brutal. However, we work hardest with those who haven’t been signed, bringing in agents and giving them opportunities. Most leave with representation eventually, but it’s not guaranteed. That’s why we stress: don’t just wait for the phone to ring. Make your own work. Be in it for the passion.”

That passion is what keeps Richards going, even through years of rejection. “I know what no feels like,” he says. “And you keep going. Sometimes it’s almost nice to get a no, because at least you know where you stand. The worst is waiting and hearing nothing back. But deep down, I know I want to do this. I’d rather regret going to drama school for a year than regret not going for the rest of my life.”

Ultimately, the tension between passion and unforgiving struggle lies at the heart of the industry. Despite having a facade of confidence and more than enough charisma, the actor is left to navigate rejection, instability, and the psychological toll of performance behind closed doors. Support should no longer be a luxury; it is a necessity. Charities like BAPAM and ABF are fighting to provide it. Schools like Bristol Old Vic and LAMDA are beginning to embed it. But across the sector, the general understanding is that provision remains uneven, and the cost of that partial silence is high.

“It is support, isn’t it?” Butler reflects. “Acknowledging that it’s a competitive industry, that you’re working really hard, and saying: this is how you look after yourself. This is who you talk to. This is where you go.”