With growing awareness of workplace wellbeing, how much longer can the theatre industry ignore the psychological toll of its most demanding roles?

The auditorium is silent, except for the sound of a young girl’s erratic breathing. She is curled up on the floor, knees pressed to her chest, her body shaking in fear. Across from her, her co-star steps forward, his heavy footsteps echoing across the stage. His movements are deliberate, asserting his dominance with each step. His face is painted with an evil smugness, a figure you only see in your nightmares. The scene about to play out is one of the most harrowing in Bad Roads, a Ukrainian play about women living through war. In this moment, the girl, a journalist, is held captive by a soldier. What follows is a disturbing sequence of violence, humiliation, and sexual exploitation.

Abi Cowen, a 23-year-old postgraduate in stage and screen at Bristol Old Vic, was cast in this mentally disfiguring scene just last year. This role is one only the bravest actors take on.“I was really intrigued as to how much this role would affect me,” Cowen says, recalling the moment she received the cast list. “I was really nervous about it. But it surprised me, it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be.”

The director made an informed decision to work with an intimacy director, acknowledging the importance of approaching the scene with a level of expertise. The work was technical, removing any emotional investment the actors may have put into the scene or character. Counts, hand placements, and spatial precision replaced improvisation and emotional memory. “When you treat it as choreography, you’re so far removed emotionally,” Cowen explains. “The intimacy coach knew it could be draining. She designed a practice for the beginning and end of rehearsals to help us separate ourselves from what was going on in the scene. We were constantly reminded that we aren’t the people in the scene.”

That differentiation is vital to the acting process. Without it, the boundaries between character and self can blur, which can be very dangerous to the actor’s sense of self. For Cowen, the choreography acts like armour. She finishes rehearsals feeling tired rather than traumatised, though she admits there are moments when a low, unplaceable heaviness settles over her. “You’re rehearsing three or four times a week, dealing with a heavy matter. Even if it doesn’t feel directly connected to the themes, of course, it’s going to affect you.”

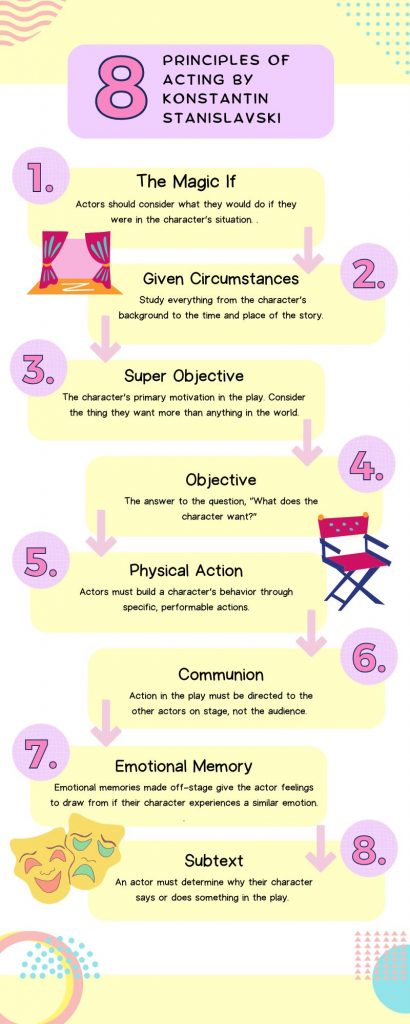

Despite practising emotional detachment, it is hard to leave behind old habits. Cowen has long employed Stanislavski’s techniques, a method of acting developed by a Russian theatre practitioner to train actors to create believable characters. Part of his principle requires drawing on emotional memory to connect with the character. This was abandoned by Konstantin Stanislavski himself for being too distressing, yet many actors still reach for it instinctively. “One of my really vivid memories was being backstage, trying to empathise and embody the character,” she says. “I’d think about her breathing and consider what it would be like to be in her situation, and mirror it.”

It is, she realises now, an unsustainable way to work. “I haven’t experienced anything close to what she went through. Pretending that I have is so intense. In hindsight, I’d focus on the physical rather than the emotional. That’s what further removed me from the situation.”

Even conversations about the play were tempered. “We kept it lighthearted. We didn’t want the heaviness of the play bleeding into our lives,” she said. “But my co-star and I did talk about how hard it must’ve been for him; he played the abuser. That’s a really hard mindset to connect with. It can affect your sense of self.”

Adam Ledger, Director of Bad Roads, has been in the industry for nearly 20 years. He began as a Lecturer in Drama and Theatre Studies at University College Cork, Ireland, and later as a Lecturer in Drama at the University of Hull, before assuming his current position as a Lecturer at the University of Birmingham. Alongside his academic work, he has directed and led performances, as well as being a part of his own theatre company.

Ledger agreed with Cowen, “The scene is so psychologically complex. For the soldier’s character, physically, he’s the aggressor, but psychologically, he’s in a fragile state. Staging it so technically gives everyone a language to work with, and the ability to say no.”

Despite his extensive industry experience, this was Ledger’s first time dealing with a subject which required intricate attention to care. “It’s the first time I’ve worked with an intimacy coordinator,” he says. “In an educational context, given the shifts in understanding around these subjects, it felt absolutely right. It wasn’t just about making sure I wasn’t asking actors to do the wrong thing. It was about us, as an institution, showing a level of care.”

For Ledger, the intimacy director’s precision is invaluable. “Everything is technical and cold; it is absolutely about where your hand goes on what count, much like choreography. The challenge is: then how do you keep that framework and put the acting back in?”

That ability to stop and to draw a line is not always part of the profession’s culture. In fact, historically, actors have been expected to put the work above themselves. “Sometimes you can’t avoid distressing material in this profession,” Ledger says. “The question is: how do we manage it?”

Delia Florea, who works as both an actor and a mental health specialist, spends much of her time helping performers navigate exactly that question. “In one of the hardest industries to work in, you can’t approach a performer with the same tools you’d use for someone in a more conventional job,” she says. “If you’re in a play where your child is dying, you go through that emotional distress day after day. Even if you’re not a method actor, it can get challenging to live with that character.”

Florea explains that this clash can be especially jarring when a role contradicts an actor’s own moral compass. “You have to love and understand your character to play them well. By doing this, you’re protecting the character. But if that character’s values go against your own, it can create a personal, internal fight. You’re protecting the character on stage, but inside you’re fighting against them.”

In extreme cases, she says, this prolonged inner conflict can contribute to more serious mental health issues, even dissociative symptoms and split-personality disorders. And yet, actors enter the profession knowing the risks. “There’s a predisposition to be more emotionally available than is normal,” she says. “That’s part of the job.”

Denise Silvey, formerly a performer, now produces the Mousetrap on the West End. She has witnessed the mental ill-health of actors first-hand. She says, “I’ve seen about six different actors who were really influenced by this one damaged character. One smashed up the dressing room. One started stripping off in the wings because he couldn’t stand the heat of playing him. He developed a twitch from the intensity of the part. It was really worrying to watch.”

As a producer, Silvey feels that she has to take on a pastoral role. She has seen firsthand how the wrong role at the wrong time can break someone. Even for experienced actors, differentiation is a difficult skill to master. She stresses that the emotional toll of performing can affect anyone. On a tour she directed, she cast a famous soap actor who eventually had a breakdown on stage. “I ended up with a 70-year-old man in my arms, crying, saying, ‘I don’t know what’s going wrong with me.’ It was devastating.”

The industry’s relentless pace, she says, makes it easy to sacrifice personal well-being in pursuit of success. “It’s so easy to get caught in that ridiculous mindset of ‘I must make a success of my acting career’ and this ‘suffering for art’ mentality. It’s better to be happy.”

The profession isn’t all doom and gloom. Saying goodbye to a role is usually a hard pill to swallow. “80% of the time, you put your costume away and you’re rather fond of them”, she says.“But there’s that 20% of the time where you think: thank God I’ve stopped playing that part.”

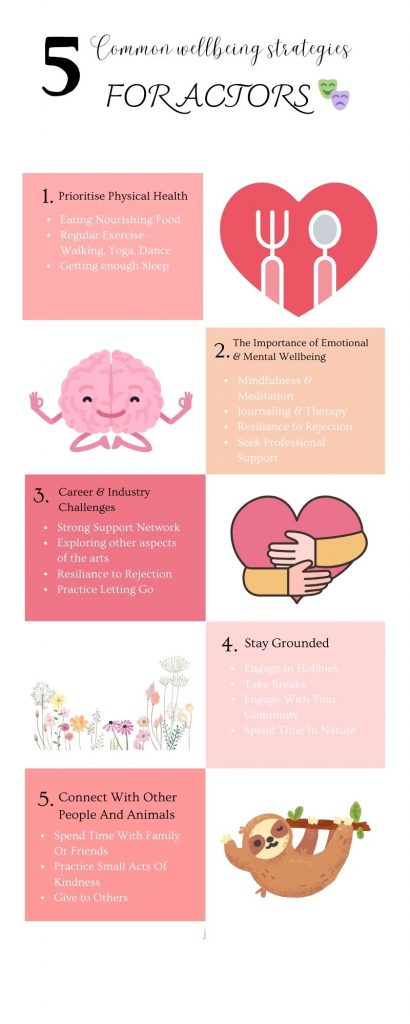

Lou Platt, founder and director of The Artist’s Wellbeing, has been campaigning for systemic reform since 2012. Her organisation provides professional wellbeing support for creatives, with all staff being both trained psychotherapists and people with lived experience in the arts.

“The existing working culture in the creative industries is structurally unwell,” Platt says. “There’s never enough money or time, so you get long hours, low pay, and inaccessible conditions for disabled or neurodivergent people, or parents. The ‘tortured artist’ archetype and the ‘show must go on’ mentality are still very much alive, but we’re starting to wake up to the fact that maybe we can work differently.”

For freelancers, she adds, the lack of HR or occupational health support is an obvious gap. “That’s why we do what we do, to provide some of those resources. But the stigma is still there. As a freelancer, you feel you have to come across as stable and consistent. You have to be enough to do the job.”

Despite this long-standing stigma within the industry, the emotional vulnerability of an actor can be highly sought after. Lou Platt explains that this quality can be powerful on stage. “There’s something about the vulnerability of that person that might be able to be channelled and create a really amazing performer,” she says.

An actor’s performance can be elevated by their life experience. “Dramas have lots of conflict, and a drama without conflict is boring. You need that conflict to progress the narrative arc, so it’s valuable to have access to a breadth of lived experience to do the piece of work.” But, she adds, this must be carefully managed: “We can be vulnerable, but the challenge is finding the creativity in that vulnerability and using it so it doesn’t get in the way of the job.”

Platt believes the skill of an actor lies not just in getting into character, but in getting out of it. “Sometimes the role is so similar to your lived experience that your nervous system doesn’t know it’s pretend,” she says. “If you have unresolved trauma, you can be more susceptible to being negatively affected.”

The support provided in the industry is improving, but still scarce. Much like Silvey, many directors, producers and stage managers are expected to provide pastoral care without the necessary expertise. “There is a gap to fill within the ecosystem of a temporary community that comes together to put on a show.” Says Platt. “How do we help people when they are affected by this profession? How do we help people who are creatively blocked because there is fear in the system somewhere? I don’t think a director or producer yet has those pastoral trainings, but they’re being asked to play that pastoral role. You do need to bring in that wellbeing expertise at the moment to fill that role.”

It is a gap that actors often feel most when inhabiting emotionally heavy roles. For Natalia Foster, the challenge came in 2021, when she played Anne Frank. She dove deep into research, reading the diary and studying the period. “I ended up having consecutive nightmares,” she recalls. “The only similarity I could draw was that I was in lockdown, like her, trapped somewhere. But on the most part, I couldn’t draw on personal experience.”

To cope, Foster compartmentalised. She rehearsed the role in set blocks of time and kept the character in the rehearsal room. “I was always taught to close my eyes and envision a box,” she explains. “In it is anything helpful for the character, and anything from my personal life I don’t want to bring on stage. You lock it and leave it there.”

Not all roles were so easy to leave behind. In One Hundred Words of Snow, Foster played the role of Rory, a girl grieving her father. Though the monologue was laced with humour, the themes hit close to home. “ I haven’t lost my dad, but I don’t have a strong connection with him. I was also feeling lonely at the time, and so was she. That made it harder to distinguish between fiction and reality. But sometimes it was cathartic, you can say and do things in character you wouldn’t in real life.”

Whilst her experience with training and support was mostly positive, Foster has experienced moments without that expert guidance. “I have left rehearsals before feeling more affected than I should. Mostly, my teachers were really attentive, but some didn’t know how to implement the correct protocol to support us as actors.”

Foster’s words echo a recurring theme across the industry; an actor’s mental state at the end of a performance often depends, not just on the actor’s resilience, but on the structures, or lack thereof, put in place to protect performers.

Whether in a rehearsal room in Birmingham, on the West End, or on the smallest community stage, the challenge is the same: to step into someone else’s mind without losing your own.

“Sometimes it’s not a question of let’s not do it, it’s a question of how do we manage that struggle,” Ledger says. “Taking those first steps to systemic change is by prioritising conversations about the fact that this isn’t you, this is your character or about maybe not rehearsing this particular scene every day. It’s about what we need to do to avoid the extreme cases of mental distress.”