Refugees are by no means a new phenomenon, but do we need to start treating them with a renewed kindness in the modern era?

In late 2015, a young Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach, dead. Alan Kurdi, barely three years old, was fleeing from Turkey to Greece with his family in a last-ditch effort to gain asylum in Canada – receiving the documents necessary for a refugee to travel from Turkey to Canada is considered incredibly difficult. The tiny dinghy was designed for a maximum of eight people, but in the early morning of September 2nd it held Alan, his brother Galib, both of their parents, and 12 other desperate refugees. This overcrowded boat barely made it five minutes from the Turkish coast before capsizing. Eleven other Syrians on the boat died with Alan, including his mother and brother.

You’ve almost certainly seen the picture of his body. Small, limp, and lifeless, he lay on a beach in Turkey, dead decades before his time. He was not the first nor the last Syrian refugee to drown in the Mediterranean Sea, but the image of him in the sand was incredibly prevalent throughout newspapers both sympathetic and apathetic to refugees. It is easy for us humans to ignore tragedy from a distance, and yet something about this poor, dead toddler in Turkey really had an impact on the British public. Even David Cameron, the UK Prime Minister at the time, claimed “as a father, I felt deeply moved by the sight of that young boy on a beach in Turkey.” He apparently wasn’t moved enough, as the UK still failed to meet the paltry 20,000 resettlement figure promised by the Conservatives, and Syrian deaths in the Mediterranean increased in 2016, the following year.

If future historians someday write about the biggest issues of the 2010s, then the Syrian Civil War would surely top the list. An unending conflict in the heart of the Middle East – an area familiar with turmoil – which has had far reaching consequences across the globe. Millions of Syrians desperate for democracy and a comfortable life found themselves caught between a despotic dictator and one of the most brutal terrorist organisations in modern history.

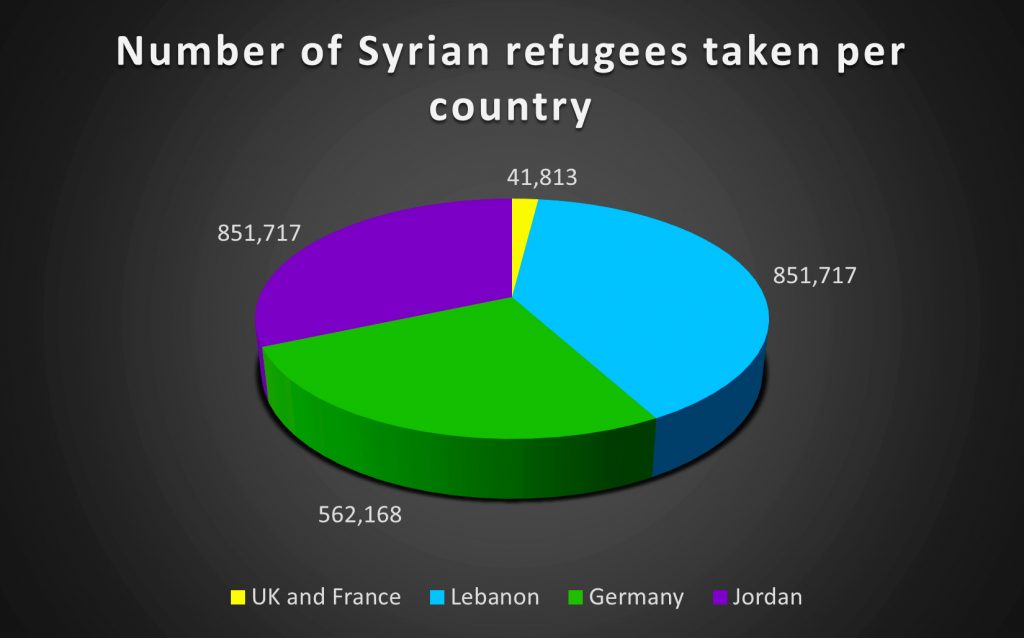

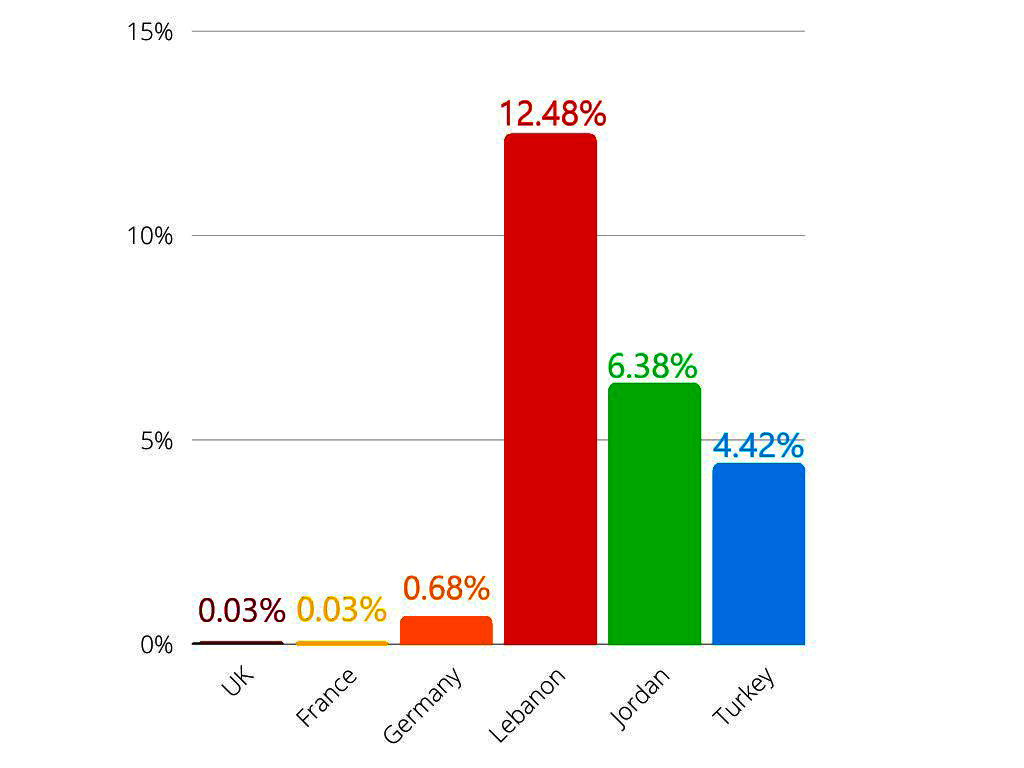

The Syrian Civil War has been among the most lethal conflicts since the Japanese surrendered in 1945. Horrors have been broadcast on the BBC and CNN, and everyone was watching. But the English-speaking world does not care. Almost all of the five million refugees fleeing Syria have settled in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, with a significant number also settled in Germany. Compared to Turkey’s massive intake of nearly four million refugees, the United Kingdom has granted asylum to a little over five thousand – with total refugee numbers in the country somewhere in the five figures.

The United States, while Barack Obama was president, provided nearly six billion dollars in aid to Syrian refugees, and during his presidency around 12,000 Syrian refugees were resettled in the USA. However, President Donald Trump won the 2016 election, and his views on refugees were diametrically opposed to his predecessor. One of his first acts upon entering the White House was to sign an Executive Order, known as the “Trump travel ban” or the “Muslim ban”, which indefinitely suspended the entry of Syrian refugees among other things.

Why is the UK so uncomfortable allowing refugees in? The answer to this question is long, multi-faceted, and incredibly subjective. A bigot might weave you a tale about birth rates and “The Great Replacement”, a far-right conspiracy which claims the world’s governments or shady individuals want to increase the non-white population of white majority countries in Europe and North America. A progressive might point you to the same theory, suggesting that opposition to resettling refugees comes from heartless bigots. The truth, unfortunately, is not quite as simple.

One suggestion could be economics. The 2008 financial crisis was a terrifying glimpse at reality, and a harrowing suggestion for how the future of capitalism might develop. Since then, the United Kingdom has been through a prolonged and visceral decay, and it’s impossible to look away. Austerity policies have gutted vital public services like the NHS, policing, and councils. Libraries, pubs, youth centres and high streets are closing at record rates. Rent and inflation consistently outflank wages, and more poorer Britons are relying on food banks and sleeping in coats, freezing throughout the winter. We know things are getting worse, but we don’t know why.

The human brain is a fascinating organ. More complex than maybe anything we’ve ever built, cleverer and more imaginative than any computer. Unfortunately for us, we used to be monkeys, and monkeys have much simpler lives. Find berry, eat berry, flee tiger. While we’ve evolved considerably beyond this rudimentary lifestyle, and predators are no longer a threat in our day-to-day lives, the instincts remain. Our brains are incredible at pattern recognition. This can lead to us falsely correlating two unique and unrelated issues, and blaming one for the other.

If you’re a white working-class Briton in your 40s, living in Bradford or Birmingham, there is no doubt you would notice an increase in non-white immigrants living in your area. This is a natural impact of global immigration, and in no way economically harmful. In fact, many studies have shown migrants have positive impacts on a country’s economy – they work, pay taxes, spend money at businesses. However, if you lost your job in 2008 and don’t follow politics too closely, you might in some way correlate your economic hardship with the increase in non-white faces in your neighbourhood. This is in no way an attempt to downplay or justify bigotry, but the correlation between economic hardship and immigration leads many into hateful conclusions.

By no means does this explain away all the problems Britain has with foreign refugees, wherever they might come from. The UK has always had issues with xenophobia, usually without even bothering to justify it. VM, a teacher currently in her 50s, came to the UK in October 1990 from Bosnia to study, learn English, and live with her husband. In April 1992, while she was here, the Bosnian war was ignited. She applied for asylum on May 13th that year.

“It was quite a difficult time, because of my family over there. I really didn’t know what was going to happen to us. It was pretty hard emotionally. My parents got imprisoned in their house by the Bosnian soldiers, and I didn’t know for quite a long time where exactly they were. I managed to find that information through some friends that they were actually still in the town.”

While dealing with the extreme stress of the war, VM also had to jump through the extravagant hoops laid out by the UK government while applying for refugee status.

“I applied for asylum on May 13th 1992, and was granted political refugee status on the 11th November 1995. It was a very long process. I was granted leave to remain, which means one becomes officially stateless, so I no longer had a country.”

“It doesn’t mean that you are British, it just means you can stay here until the government decides otherwise. I was granted indefinite leave to remain in October 1999, and then I was given citizenship in March 2002.”

A full decade passed between her applying for refugee status and finally being given British citizenship. The UK government put up significant roadblocks for her and for many other refugees before and since, even though there is no logical reason for it. Refugees have the potential to be positive contributors to a country’s economy with the right support – not that a refugee’s economic potential should factor into the humanitarian effort put in to help them.

As well as the Kafkaesque nightmare of the UK refugee process, VM has had to deal with intolerant British people throughout her time here.

“I’m a very positive person, and yes I know that there have been incidences where people would say ‘You effing foreigner’. There have been situations like that, but like water off the duck’s back I took it okay and thought to carry on.”

“It was very hard to get accommodation because people just would not want me to rent a place. At one point I had to look at 35 different flats and nobody would have me.”

This prejudice was not limited to struggles while the Bosnian war was going on – people still treated VM and her family with distrust and hostility long after the war had ended.

“My son was beaten up simply because he was a refugee when he was very small, 11 years of age. I had a situation when a student of mine said to me ‘I’m sorry, I can’t stay in your class because you are a refugee.’ That was in 2001.”

Compounding the drawn out and tentative refugee process, intolerance from the people around you, and the emotional stress and fear for your family back home is a lot for one person to deal with. This all goes on top of the day-to-day stresses you would normally experience, which is already plenty. Luckily, not everyone is always awful, and children who have been moulded into bigots by their parents can still change.

“She (the student) actually came back six months after, knocked on my office door and said, ‘I came to apologise because you’re actually a very cool teacher and I couldn’t stay in your class because my parents said I couldn’t talk to refugees’.”

VM’s experiences with the wider British public were improving, until the Brexit referendum in mid-2016. Race related hate crimes have spiked since the referendum result, and while this follows an upwards trend seen since before the referendum it cannot be denied that inciteful rhetoric was normalised by the leave campaign.

“Since Brexit I have definitely felt that people are again spreading this feeling. I get asked again stuff like ‘When are you going home?’. Where do you want me to go? This is my home.”

“I think in many ways people feel they have been given a green light to express they don’t want other people. It’s a subconscious refusal of people from a refugee background. If the government is saying: ‘We don’t want them,’ why shouldn’t ordinary citizens think that?”

The world is an incredibly chaotic place, and it’s unlikely that refugees will become a thing of the past anytime soon. Just like the Syrian Civil War, conflict can arise anywhere across the globe, and with conflict comes the need for ordinary citizens to escape. On top of this, as the effects of climate change get more and more pronounced, people will likely begin fleeing low-lying coastal areas en-masse. For this reason, countries like the UK need to start promoting a more compassionate and accepting environment for refugees and anyone fleeing an upended life – wouldn’t we want the same for us?