In a shock move that reflects China’s ‘half-open half-shut’ cultural policy, singer Li Zhi has been banned by the Chinese government.

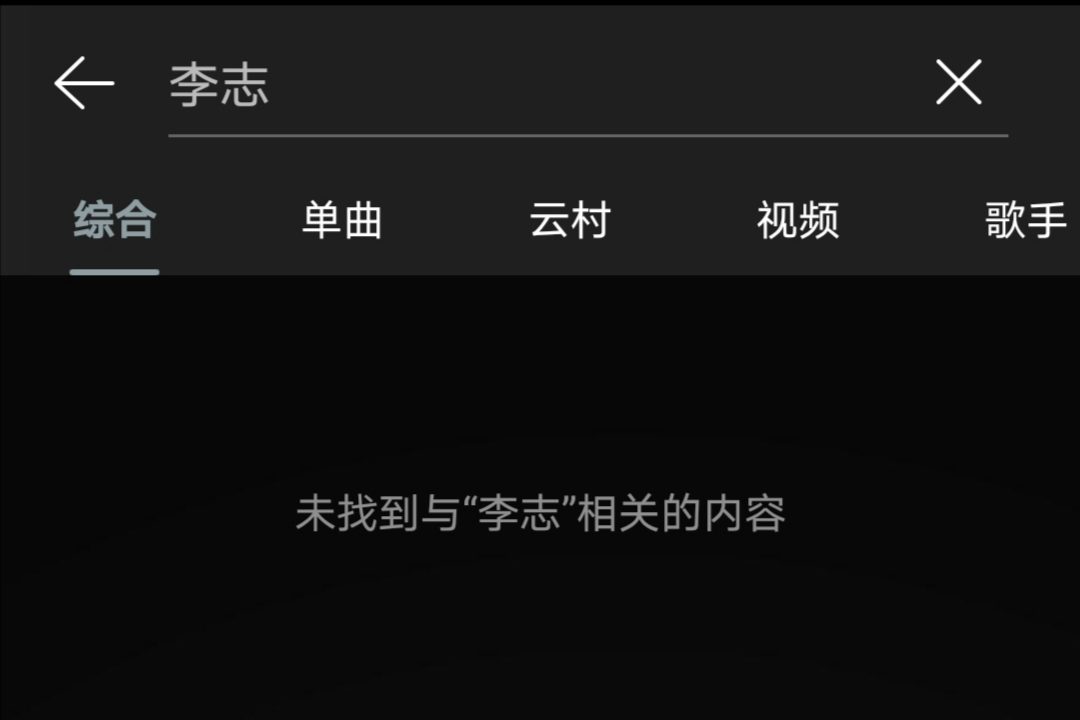

One day last April, Shang Yu turned on her phone to play music but was surprised to find that her favourite singer’s songs were all gone. She thought it was due to the copyright running out until she couldn’t find any information about the singer on other music apps either. Shang Yu suddenly felt a chill—how could a famous singer disappear like steam without a trace? A few days later, she came across a headline in the news: Singer Li Zhi banned for “misconduct.”

Who is Li Zhi? He calls himself “Mr Li of Nanjing,” a character well-known to lovers of ballads. Fans refer to him affectionately as “Brother B” and China’s Bob Dylan. For those who know little about Li Zhi, however, the government’s decision to block him is puzzling. Indeed, Li Zhi is a devoted musician. His whole life is songwriting, rehearsing and touring. He managed his band with a tight rein and spent hours honing his skills. So, what makes him the target of the Chinese government?

In 1997, Li was admitted to Southeast University in Nanjing, one of the best universities in southern China–great news for a young man from the countryside. Even now, millions of Chinese students are working day and night to get into higher education. However, Li Zhi disliked the school’s education system and dropped out the next year. He tells the story with no expression on his face as if it were a trivial matter. At that time Li has already shown his art temperament. A few years later, he took a 14-hour train ride to Ningxia to watch a rock concert which shook him to the core. Once back in Nanjing, he borrowed 5,000 yuan and recorded his first album.

“Li Zhi is a poet dressed as a singer,” says Luo Tuo, a music critic, and many of Li’s fans would agree. “His songs are full of love for life, real emotions, critical consciousness and rebellious spirit,” Shang Yu gushes with excitement. She once flew thousands of miles for one of Li Zhi’s concert. But Li Zhi’s outspokenness and rebellious ways do not go unnoticed in a place he calls “an abnormal country.”

Though Li wasn’t affected during President Hu Jintao’s tenure, Xi Jinping’s tightening of public opinion did not bode well for a musician who has written so many critical songs. In 2017, Li launched an ambitious tour of 334 cities. Although he doesn’t make it clear whether 334 implied a commemoration of the Tiananmen Square event which happened on 4th June 1989, it was enough to antagonise the government. At each concert, there would be local government officials monitoring, to make sure nothing “bad” happens. Under huge pressure, Li insisted on continuing with his planned tour though he didn’t reach the end of his journey.

There has been more than one case in China of people being punished for vague accusations like “bad behaviour.” Before Li, there had already been countless Li Zhi. Many of Li Zhi’s fans had braced themselves for such an outcome since the untouchable taboos are not secrets in China. From this perspective, China’s cultural space is “half-open half-shut”.

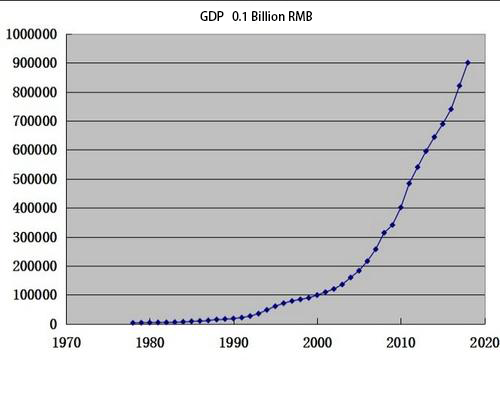

Liu Xinwen, a professor of philosophy at the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (UCASS), says China’s social form and structure are markedly different from that of Western societies as well as North Korea. Countries like the UK and US, are fully open in political, economic, cultural and other aspects, while North Korea is at the other extreme — closed and conservative in either direction, despite recent attempts to attract foreign investment for economic development. Many people in the “free world” mistakenly think that China is another North Korea. However, since Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1978, China has embarked on four decades of economic liberalisation — the so-called “Reform and Opening-up” — which has been followed by a major opening up of the cultural sphere. Hollywood films would even be released first in mainland China; Western culture has become part of the daily life of Chinese people, especially for the middle-class. On the other hand, Deng seized power from the liberal leader Zhao Ziyang (the President then) in a coup, leaving China with no hope of substantive political reform for at least half a century. The high concentration of power in one man inevitably leads to cultural censorship and silencing. Therefore, China’s cultural field has been in a “half-open and half-shut ” situation.

Liu Xinwen’s insightful analysis above is only a few discussions with his students. As a teacher in Beijing, a little bit of critical thinking is the most that he can do in the classroom. Whenever it comes to some “sensitive topic”, he tells the students not to discuss it outside the school. While the truth is, school is not always safe either. Not long ago, Liu Xinwen’s colleague, a teacher named Zhou Peiyi in the Law School was expelled from UCASS for making “inappropriate comments”– the truth is that she made some comments criticising the lack of freedom of speech in China. Zhou was reported by a student, whose identity remains unknown. Her dismissal didn’t cause a big stir in China. Most of the information spread on the Internet was quickly removed before it went viral. Before Zhou’s sacking, several teachers in Beijing had already been disciplined for criticizing the current system. Many were state-level scholars from Peking University and Tsinghua University.

At the gate of UCASS, the motto “Study diligently, Think carefully, Distinguish clearly and Just do” is inscribed on a huge stone tablet. From the outside, it seems no different from other advanced and modern university. Like any other educational institutions in China, however, UCASS is only ‘half-open’. Since it is a purely social science university, teachers and students are even more careful to avoid “getting into trouble”.

Last year, three Chinese universities rewrote their charters to emphasize their loyalty to the party over and above traditional values. It caused protests from teachers and students all over the country but the internet police were clearly efficient enough. Complaints and angry voices disappeared from the web in few days.

“The government doesn’t even bother to do the surface work,” said Qi Sheng, a student at Fudan University, lamenting the behaviour of his alma mater. He and his schoolmates spontaneously sang Fudan University’s school song on campus to show their indignation. The second line of this hundred-year-old school anthem is striking: “Academic independence, freedom of thought, progress, progress!”

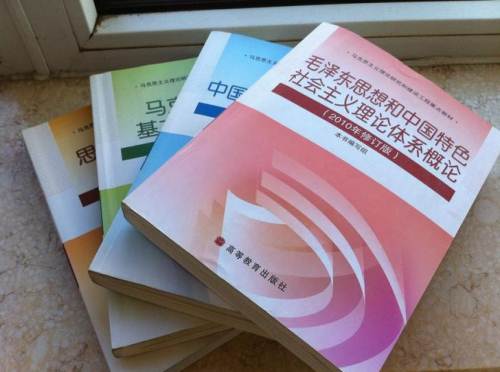

Qi Sheng knows clearly that his discontent can’t change anything, and in fact, Fudan’s “independence” and “freedom” have existed only in the school song for long. Any university in China is directly under the control of the Communist Party, whether it changes its charter or not. Political studies are compulsory in all universities and account for a large proportion. Students must study the spiritual achievements of “great leaders” such as Marx and Mao. Without passing these courses, students are not able to graduate. For Qi and most of his friends, these courses are boring as there is a lot to memorize.

Next year, Qi Sheng will graduate from Fudan University. As a journalism student, he will not enter the news agency in China, although writing and photography are his favourites. He had interned in several news outlets before and was disillusioned with journalism. “The top thing I need to be careful is not to get the leaders’ photos in the wrong order; a single phone call from an angry mayor or governor can take down our stories at any time.” In the Press Freedom Index, China has been consistently ranked very poorly on media freedoms. For 2019, China ranked 177 out of 180 nations.

It is no secret that the press is controlled by the government, more precisely, the Communist Party. The biggest state-run news outlets such as People’s Daily has openly declared itself the “mouthpiece” of the Party. Qi Sheng does not want to go against his journalistic idea and “sing the praises” of the party, so he would rather work for a network company where exists no so many restrictions. “The spring of Chinese journalism has passed and now we welcome a bitterly cold winter.”

The “spring” is the time before Xi’s ruling. Previous liberal leaders like Wang Yang eased the restrictions on the media. China, especially in the southern area, enjoyed a period of relative freedom. Newspapers like Southern Weekend were once beacons for many readers, including Qi Sheng. Its slogan reads: “Let the weak be strong, let the pessimist move on”. Now, however, Southern Weekend has kept its mouth tight and “behaved well” for many years, which marked the winter or journalism.

The “winter” has gone far beyond China’s education and media, but also influenced Chinese art and culture. Feng Daqian, a fan of Lizhi, bought tickets to Li’s concert in Chengdu then was told it would be cancelled. For Feng, the shock was like a cold shower. “Alas, in such a big country, there is no room for a Li.” Although not a fan of Li’s voice, Feng was drawn to the meaningful content of Li’s lyrics. “I admire what he was doing,” he said. “He is a man of depth”.

However, there is a systematic contradiction between people’s critical thinking and an autocratic government. Liu Xinwen believes that the economic boom and political conservatism are like twins– the two opposite forces lead to the half-open/half-shut nature of Chinese culture. Although the latter force to a certain extent maintains the stability of the regime, it also hinders the freeing of citizens’ minds and Chinese culture integrating into the outside world. “If the speaker must eulogise, if the truth is a sin, the nation is doomed…”

Although political pressure has limited artistic and cultural expression, the popularity of the Internet brought about by China’s rapid economic development has opened up Chinese culture to a remarkable extent. Some fans said that what Li Zhi wanted to express had “taken root”. After Li was banned by the government, the Chinese media, as expected, chose to remain silent or even cover-up, while rumours still ran wild online. Although network managers have put “Li Zhi” into the sensitive list, netizens have made full use of all kinds of memes to show their rebellion.

This kind of “underground” approach to fighting the authorities existed even before the birth of the Internet. Three thousand years ago, the emperor was warned: “closing the mouth of the people is like stopping the flow of a river”. Eliminating different voices is a difficult task even for the Communist Party which has more than 90 million members. On the Chinese Internet, “wall” became a meme which indicates that netizens are already aware of their situation. But as the old saying goes, “there are rules on the top and countermeasures on the bottom”. Netizens are adept at playing with words. They invent all kinds of symbols and memes to fight. Before Li was banned, the name “Zhu Yuanzhang” was blocked because many people used it to satirize President Xi. Zhu is an ancient Chinese emperor and well-known for founding a huge spy organization “Dong Chang ”to monitor his people. And such stories happen every day.

Li Zhi says he doesn’t regret what he did and is happy that he has followed his heart and kept doing the right things. “If I don’t do these things, I’d not take it easy because I feel guilty at doing nothing. I have always been a person who treats money like dirt and only hopes the descendants can live in a civilized and free world.”

Would people like Li Zhi make any change fundamentally? Some scholars doubt it. “Isn’t the Internet controlled by the government?” says Liu Zhaoxia, a journalism scholar at UCASS. She believes that netizens are only a loose group of individuals. The government’s aim is to ensure the stability of society as a whole but not let everyone happy. People at the top would deliberately ease some restrictions to release people’s anger. But that does not mean netizens’ victory. “China’s cultural opening ultimately needs political opening.”

A piece of good news for Li Zhi’s fans is that Li’s block will be over at the end of 2020. Li is preparing his comeback and hopefully, fans can enjoy his concert again next year. But the “334” tour is not sure for going on.