Schools in Wales are ready to teach students sex and relationships, why are parents angry about a curriculum aims to teach accurate sex content and inclusivity?

Around 60 parents were rallying from Cardiff Castle to the Senedd to protest against mandatory sex education. It was February. In April, the same group took the Welsh government to court hoping to make sex education not compulsory claiming that their time-honoured rights are being taken away.

Parents have a role to teach children about sex, says Amy Stuart-Torrie, a senior project worker at YMCA Cardiff who runs one-to-one sessions with young people regarding questions on sex. “But not all young people have a family home where they can have this conversation which is why schools have got an important role to play.”

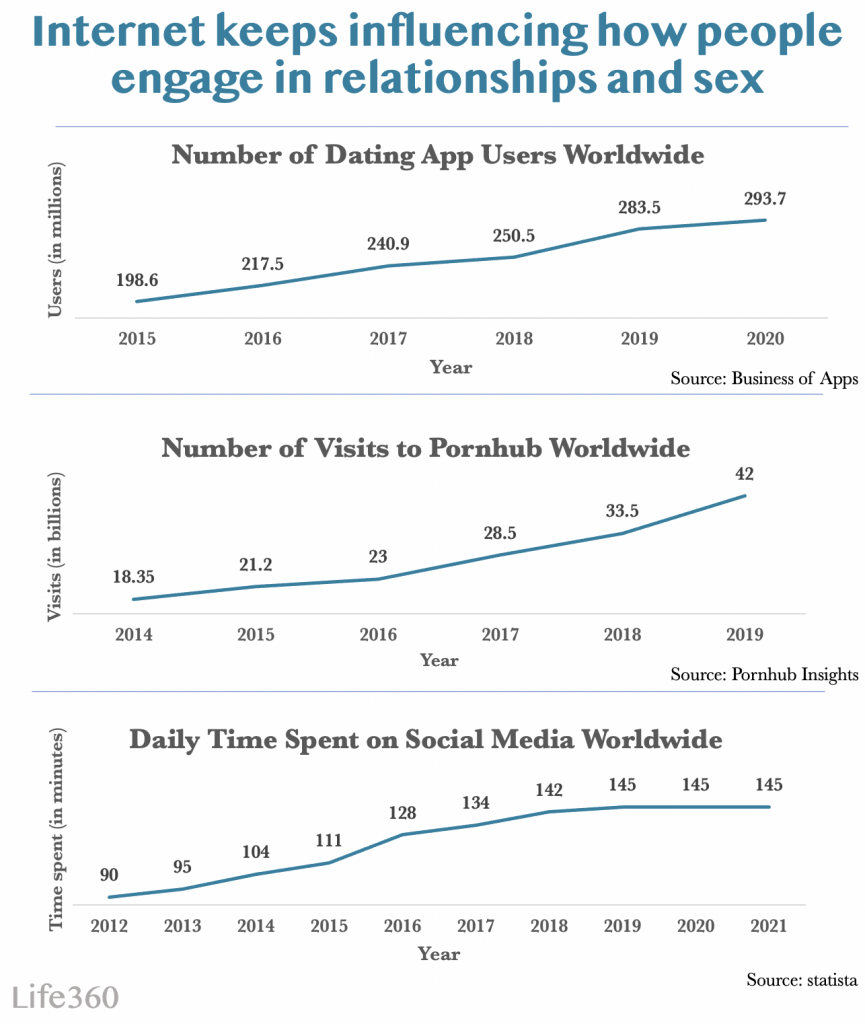

If students cannot get the information they need at school, they may go to the Internet for answers. Sexual information on the Internet, Stuart-Torrie observes, has played a big role in pupils’ decision-making. However, the information may not be accurate.

Stuart-Torrie believes compulsory sex education at schools would be a remedy to bring the conversation into students’ daily lives. “Hopefully keep themselves as safe as possible and to have the opportunity to discuss and explore these topics that for a long time have been sort of taboo and sensitive. And not everyone feels comfortable talking about them,” she says.

Content about sex is everywhere in this technological world, where social media become part of the reality of our lives. However, the accuracy of information is not guaranteed. Pornography is one type of inaccurate information. Last month, teachers at the National Education Union conference shared concerns about the impacts of pornography on students and called for more training to help schools.

When it comes to sex, young people can be vulnerable when they receive false information it would post harm on them when encountering sex themselves.

I strongly believe the more we normalise these subjects the less chance there will be of youngsters getting bullied for things like their sexuality or gender identity.

Caroline Hemmingham,

a parent of two and a columnist

Given the overloading of information available online, parents, however, don’t necessarily think schools should step forward to bring sex into the curriculum. Some believe the code proposed by the Welsh government is not workable.

The sex education code is not age-appropriate, according to ITV’s Loose Women panellist Denise Welch. “The fact is, I think that five is too young to be chatting about sex education,” she said on one episode of the show.

Caroline Hemmingham, a parent of two and a columnist, thinks compulsory sex education at a young age helps students to learn accurate information about sex. “I strongly believe the more we normalise these subjects the less chance there will be of youngsters getting bullied for things like their sexuality or gender identity,” she writes in response to this article. “I also think it might lessen the risk of youngsters learning about sex for themselves by watching porn – which I think is a very concerning thought.”

Moreover, worry about students learning sex at an early age may be excessive. According to the code, students will learn knowledge about sex gradually. From seven years old, pupils will learn about reproductive organs, fertility and the processes of reproduction. Before this stage, students, the code states, will learn about terms for different body parts.

Stuart-Torrie thinks that the sex education code is age-appropriate. Nonetheless, she understands why some parents would oppose the code out of scare. “They perhaps see in social media and see these alarming things. I have seen some shocking things like they’re going to be teaching 4-year-old about porn and things like that. That’s not the case. That’s not going to happen. So, they’re hearing that from people and that is scary because you would not want that,” she says.

The problem around sex among pupils is becoming severe in Wales. The majority of students in Welsh secondary schools reported that they had seen peer-on-peer sexual harassment, according to Estyn, the education inspector in Wales. Those actions, for example, cat calling, sending nude photos and body shaming, happened more often online than offline.

It completely denies the rights of religion and any families whose values don’t align with this sex education.

Lucia Thomas,

a campaigner from

Public Child Protection Wales

The controversy goes beyond the matter of sex education. The code called the Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) Code, suggests that it is not just about the teaching of sex in a biological sense. It contains three strands, one of which is “Relationships and Identity”. Students will be taught about the awareness of social norms on sex, gender and sexuality from seven years old. They will then learn to respect people about sex, gender, and sexuality including LGBTQ+ people from 11 years old.

Parents claim that the teaching of gender identity is wrong in nature. “We do not support teaching gender identity, because there is no evidence for it,” Transgender Trend, a concerned group on the medical transition of young people, writes in response to this article. “Children should not be taught that their personalities or interests mean that there is something wrong with their bodies. It is not possible to be born in the wrong body,” the statement reads.

Lucia Thomas, from Public Child Protection Wales, an organisation that is suing the Welsh government, said in an interview that the code was dressed up as a high-class inclusivity education. “Well, in fact, it’s anything but inclusive because it completely denies the rights of religion and families. Deny the rights of any families whose values don’t align with this sex education. So inclusivity is definitely not something that it is,” said Thomas.

The report by Estyn last December suggests that LGBTQ+ pupils have substantial personal experiences of verbal homophobic harassment. Many claimed that homophobic bullying was happening all the time.

Meanwhile, Stuart-Torrie believes that teaching gender identity is important to make schools inclusive. “It’s like we might have a training session on knife crime awareness, we’re not all going to become people who go around and commit knife crime,” says Stuart-Torrie. “It’s not about asking people to question their gender and sexuality. It’s just making education relevant to all the young people.”

There might be a need to advocate the rights of the minority in every aspect of society and schools could be part of the changes. Hate crimes against people based on sexual orientation have doubled in four years in England and Wales, according to Home Office. Campaigners have been calling for the protection of LGBTQ+ people after the murder of a bisexual man in Cardiff.

Another criticism regarding the new sex education code is the doubts over the ability of schools and teachers to deliver the knowledge. During the rally in February, protesters said they didn’t trust the teachers with what will be taught. “We don’t feel teachers have received proper training for this,” said Rachel Evans, the spokesperson for the group.

Teachers in some schools might not have enough training on teaching sex, according to Stuart-Torrie. “I do feel for the schools because they’ve been told that this is going to be compulsory but there hasn’t necessarily been any packet or training, or funding for member staff,” she says. However, she says there is training available for schools so they can catch up on it if needed.

She also thinks that schools can adapt their teaching to fit students’ needs based on the framework of the code. Surveys can be used to know what students need and worry about. “And the teachers know the young people, don’t they?” she says.

As a parent, Hemmingham teaches her kids about sex back home, but she still thinks having sex education in schools is beneficial to the children. “I think by removing a child from the classes, you are denying them a really important part of their education and they will absolutely go looking for answers to their questions elsewhere,” she writes. “By removing them will also make them more intrigued about the subject – when it shouldn’t even be a big deal in the first place.”